Christmas is exciting, and this was no different—but how could that be when everything about life was suddenly so different? The tree was glowing in our living room with all of the familiar ornaments we had put on it since I was a kid. The presents were wrapped underneath, ready to be opened. Our dog was running around like crazy, because she knew there were definitely a few toys wrapped up for her to open as well. It was Christmas in our home again—no different, but different.

The anticipation that Christmas always builds was building for all the wrong reasons. Apprehension clouded over the entire morning. It was Christmas 2013—the first Christmas without my Dad. And no matter where I looked, even though he wasn’t there, all I saw was him.

I sat on the couch where I always sat when we were opening gifts. Mom came down the stairs and sat in the chair across the living room. And we just sat there for a moment. We were usually always waiting on Dad. He would wake up, and just lay there for a while, and change his clothes, and brush his teeth, and after 15 minutes of harassment from me as I held back from ripping the presents apart, he would eventually come down the steps. But on this Christmas, no matter how long we waited, I knew he wasn’t coming. But I didn’t want to admit it.

I loved Christmas, but in that particular moment I wanted to be anywhere but sitting around the foot of our Christmas tree. It felt wrong. How could we even celebrate Christmas? Dad wasn’t here, and it wasn’t Christmas without Dad. How could we even bring ourselves to smile when we opened presents, knowing that this was Christmas from now on? I felt guilty—beyond guilty.

For better or for worse, however, I kept a brave face on for my Mom—even though I knew, deep down, she was having the same exact feelings of guilt, emptiness, and sadness.

We just didn’t know how to do this. There’s no manual or textbook on how to celebrate a holiday after you lose a loved one. It felt like we should be doing something different, but it also felt like we should be holding on to everything we had done previously so the tradition would always be there, even if my Dad wasn’t. Everything we did felt wrong, even if it was probably the right thing to do. Christmas had taken on a whole new emotion—I went from loving Christmas to just wanting to get it over with as quickly and painlessly as possible. It was heartbreaking.

And it was heartbreaking because Christmas was always such a wonderful, wonderful time in our home. It was a perfect balance of excitement and tradition that all Christmases should be. Mom would make our favorite breakfast quiche and cinnamon rolls, filling the house with the smell I’ll always associate with the holidays. We would stay in our pajamas all day long and play with the toys and games my parents had bought me. We would watch A Christmas Story way too many times, and my Dad would laugh at the same jokes over and over and over again (especially when the lead up to the tongue-on-pole fiasco). It was Christmas the way Christmas was supposed to be.

And now, all of that was gone. The food and the gifts and the movie-marathon were still there, but a dark cloud of emptiness enveloped the whole thing. It was now everything that was wrong with Christmas—going on without my Dad and still celebrating. It felt wrong to want Christmas to just be right again.

But I looked at Mom, and she looked at me, and we both knew that we had no choice. We couldn’t simply abandon the tremendous memories we have of the 25 Christmases we got to spend as a complete family. Those were important treasures, and we couldn’t hate the previous holidays because we weren’t enjoying the current one.

So, we went on. We passed gifts between the two of us, interjecting a few for the dog, Lucy, as she grew restless. We smiled when we opened presents, and thanked each other just like we always had. It felt strange just giving gifts between the two of us, but if I closed my eyes periodically, I could pretend that my Dad was still there with us. And even with my eyes open, I could still feel him there with us in that moment. A few minutes into the gift-giving, however, I found my Dad right there with me in a much different fashion.

Dad had always been the professional gift wrapper in our household. His attention to detail and desire for perfection bled into every aspect of his life, and Christmas gift wrapping was no exception. It may have taken him a ridiculously long time to do, but his creases were perfect. Each gift was a work of art, and each gift wrapping had its own personality. He was very creative when it came to unique bow combinations. He would use ribbon in interesting combinations and patterns to create different effects on the boxes. On occasion, he might try and trick you by taking a small gift and putting it in a huge box (or multiple boxes set inside each other like Russian nesting dolls). I never gave him enough credit for how well he wrapped presents, probably because I was so jealous that mine looked like they were wrapped by a three year old.

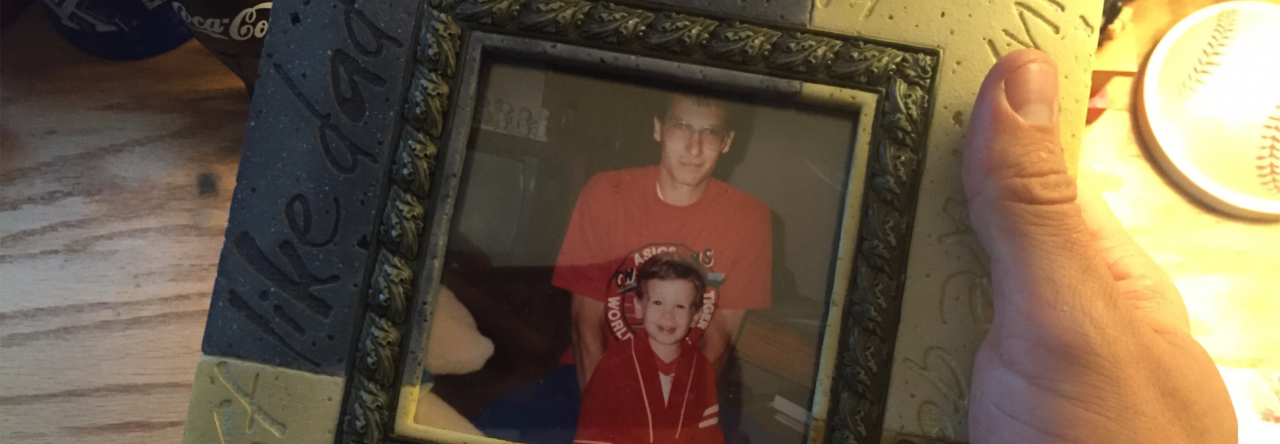

The gift tags were always his finishing touch. Dad would always label each package, but it was rarely a simple “To: Ty / From: Dad”. There was only usually one tag that would have that standard moniker, but the rest were all creative. Each one had to be goofy or silly or different. “To: Ty / From: Santa.” “To: The Boy / From: The Dad.” “To: Tyrone / From: Pops.” “To: Bub / From: Papa Elf.” Although each tag was familiar in that it was written in Dad’s recognizable, precise, ALL-CAPS handwriting, each tag was distinct and had its own personality. Most of the time they were goofy and corny, just like most of my Dad’s jokes. I’m sure, over the years, there were a few eye rolls from me, an embarrassed son, but my Dad never quit smiling when he saw me read them.

But on that first Christmas morning without him, my eyes grew wide when I grabbed a seemingly normal package. I looked down at the tag, and thought my eyes had to be playing tricks on me. There it was. The precise handwriting in all capitals that I had begun to emulate as a seventh grader. The sharpie that he always used to label his gifts. I looked at the package, and there it was—a label, written by him, that said “To: Ty / From: Dad”.

I looked up at Mom, completely astonished. She looked backed at me as tears streamed behind her glasses. “I found a few of them when I was getting out the gift wrapping stuff. It makes it feel like he’s still here with us, doesn’t it?”

Then, I lost it. All the emotions I had been trying to hold inside burst forth. All the hurt and emptiness and sorrow I was feeling in that moment exploded to the surface, and there was no holding it back. “I miss him so much,” was all I could get out, over and over.

Mom got up from her chair, walked over to me, and just hugged me. We cried together, as the reality of our new holiday tradition set in.

Each year, I get a few packages that have my Dad’s Christmas tags on them. And each year, it’s gotten easier and easier to look at them and remember the great Christmases we spent together, rather than obsessing over the heartache that I so often feel. It’s gotten easier to watch A Christmas Story and laugh at the parts we would have laughed at together. But just because it’s easier to deal with doesn’t mean it hurts any less. The pain is still just as real as it’s ever been, but over the years since Dad’s passing, I’ve learned to appreciate the great times we had together rather than obsessing over the time that was stolen from us. And I’m thankful that I have a Mom who loved me enough, even in the midst of her own heartache, who still wanted Christmas to be a special time filled with love for one another.

I rest easy in the midst of the pain when I remind myself of the reasons why we celebrate Christmas. Even though my Dad might not be there to open the gifts and enjoy the food, I have a Heavenly Father who sent his Son to this Earth so I wouldn’t suffer alone. I celebrate because God knew I would encounter this pain, and he cared enough to do something about it. I have no doubt those little Christmas tags were a gift from God when He knew I would need them most. They were the reminder I needed when life felt too tough.

And I also rest easy knowing that I will celebrate Christmas again with my Dad, and it will be an even better celebration than the ones we had when we were together here. That’s really hard for me to come to terms with! Those Christmases growing up felt so perfect, but God tells me that the ones I spend when we are reunited in heaven will be even better? When I read my Bible, it convinces me that every day in Heaven, not just one day a year, will be like Christmas. My mind can’t fathom that level of happiness. My heart can’t contain that type of love. But my soul longs for it, and I know that I’ll be laughing again with my Dad someday and celebrating Christmas with him again. I can’t imagine how God could make his gift-wrapping skills any better. But as long as those old familiar package tags are there, I’ll be happy.

Until then, I’ll make the most of the Christmases I’m given with the other people that I love. I’ll laugh when I’m having fun, and I’ll allow myself to cry when I miss my Dad. But most importantly, I won’t feel guilty or ashamed for experiencing either emotion. I’ll thank God that I long for those Christmases of long ago, because they must have been pretty tremendous for me to want them back so badly. It’s a weird thing to long for something you know you can never have, but it’s reassuring when you know, deep down, you’ll have something so much better to celebrate on the other side.

Dad, Every time another Christmas tree goes up, I shake my head and shed a tear because it feels like it was just yesterday we celebrated our last Christmas together. You loved that time of the year. You made the season so special for Mom and me, and I’ll never forget the tremendous memories we made together. At times, it really doesn’t feel right to even celebrate Christmas. I feel guilty having fun and smiling without you here to join in. But I know you’re watching, and I know you’re still smiling and laughing. Dad, thank you for giving this boy a lifetime of memories that are more valuable than any other gift you ever gave. Thank you for showing me what it’s like to love other people the way God loves us. The sacrificial love that God showed us when He sent His Son to this world is the same love you showed to everyone you came in contact with, whether it was Christmas or not. This season, help me live more like Him and more like you. Until a better Christmas, seeya Bub.

“Every good present and every perfect gift comes from above, from the Father who made the sun, moon, and stars.” James 1:17 (GW)

Dad, I would do absolutely anything to go back to that moment when you came home and change the way I acted. I know you don’t want me to feel guilty, but now that I know more about what you went through, it pains me that I treated you the way I did. It breaks my heart to know how alone you must have felt in that moment, and now that our time together on this earth has ended, I would give anything to have it back. Had you been able to simply “snap out” of your depression and never suffer again, I know you would have. I want you to know that I would never judge your love for me and our family based on an illness that periodically overtook your mind and senses. Although I’m so thankful you don’t suffer from the darkness you once felt anymore, I wish I had just one more opportunity to hug you and tell you that I’ll always love you. Someday, I know I’ll be able to hug you once more. Until then, seeya bub.

Dad, I would do absolutely anything to go back to that moment when you came home and change the way I acted. I know you don’t want me to feel guilty, but now that I know more about what you went through, it pains me that I treated you the way I did. It breaks my heart to know how alone you must have felt in that moment, and now that our time together on this earth has ended, I would give anything to have it back. Had you been able to simply “snap out” of your depression and never suffer again, I know you would have. I want you to know that I would never judge your love for me and our family based on an illness that periodically overtook your mind and senses. Although I’m so thankful you don’t suffer from the darkness you once felt anymore, I wish I had just one more opportunity to hug you and tell you that I’ll always love you. Someday, I know I’ll be able to hug you once more. Until then, seeya bub.

On many Sundays, my Dad would fulfill his churchly duties and serve as an usher, taking up the morning offering. On this particular Sunday, he made history in our church by doing something no other offering taker had ever done (or most likely would ever do again). After the music had concluded, our pastor, Ted, made his way to the front of the stage in between the tear-stained altars, and beckoned the offering takers to come forward and grab their plates. My Dad liked Pastor Ted for many reasons, and one of those reasons was that his humor, as juvenile as it may have been at times, was always in sync with our pastor’s.

On many Sundays, my Dad would fulfill his churchly duties and serve as an usher, taking up the morning offering. On this particular Sunday, he made history in our church by doing something no other offering taker had ever done (or most likely would ever do again). After the music had concluded, our pastor, Ted, made his way to the front of the stage in between the tear-stained altars, and beckoned the offering takers to come forward and grab their plates. My Dad liked Pastor Ted for many reasons, and one of those reasons was that his humor, as juvenile as it may have been at times, was always in sync with our pastor’s.