(This is the newest feature in “Dad’s Rules”, a recurring series at SeeyaBub.com. To learn more about the “Dad’s Rules” series, check out my first installment.)

Dad’s Rule #119: Socks are part of a specific pair. Therefore, they shall be numbered.

“Dad, I’m seriously afraid to even ask you this question, but…why do you have 5’s written on the bottom of your socks?”

I don’t remember when the craziness started, but my memory tells me I was in college or had just recently graduated when I noticed Dad’s newest quirk. I was sitting on the couch watching television when Dad came bouncing down the steps in his usual, peppy way.

“Hey, Bub!” he said with his familiar smile and sparkling personality. I returned his greeting as he moved towards the recliner that sat in the corner of our family room. Dad loved kicking his feet up in that recliner, but this time, there was something noticeably different once his legs were kicked up.

For as long as I could remember, my Dad had mostly worn big, thick, fuzzy, wool-type socks around the house. Yes, on occasion he would wear typical white, athletic socks made by Nike or Under Armour; but mostly, the big woolly types were his favorite. Maybe it was a function of his years working outside in carpentry settings accompanied by frigid temperatures. Maybe it was a function of him just trying to embody the whole “Dad’s Wear Weird Clothes” stereotype. Regardless of the origin or motive, he wore them most of the time—especially during those unpredictable Ohio winters. He would pick up new pairs at Bass Pro Shops, Quality Farm & Fleet, or other outdoorsy stores that he frequented (mostly outside of Mom’s purview). Some of the socks were white, and others came in different colors, usually with a gold or other-colored toe and ankle patch complete with a colored ring around the top of the sock. I can picture them as clear as I saw them on that day when he popped his feet up on the recliner; but on that day, there was something drastically different about the socks he wore.

Written on the bottom of each sock in black, permanent ink in Dad’s familiar, precise script, was a huge “5” for no apparent reason.

This had to be good. Or extremely embarrassing.

“Dad, I’m seriously afraid to even ask you this question, but…why do you have 5’s written on the bottom of your socks?”

Like Sherlock Holmes getting ready to divulge the certain facts of a case that only he could divulge, Dad took a deep breath with a smug look on his face and launched into his explanation. “Because socks wear differently. Over time, the heels and toes start to get worn thin, and you can’t be comfortable in one thick sock that’s brand new and one thin sock that’s about to get a hole. So, I number them, and I don’t have to worry about that problem any longer.”

Like Sherlock Holmes getting ready to divulge the certain facts of a case that only he could divulge, Dad took a deep breath with a smug look on his face and launched into his explanation. “Because socks wear differently. Over time, the heels and toes start to get worn thin, and you can’t be comfortable in one thick sock that’s brand new and one thin sock that’s about to get a hole. So, I number them, and I don’t have to worry about that problem any longer.”

For one of only a few times in my life, I was literally at a loss for words.

After I picked my jaw up off the floor, I sat up calmly on the couch and began to ask Dad about his day at work. Had he inhaled any fumes in high doses? Had he excessively sniffed the permanent marker that he had used to write on the bottom of his woolly socks? Blunt force trauma to the head? Did he have a new side-job working with fashion line whose goal it was to create clothes for Dad’s that would absolutely mortify their children?

No matter how hard I pushed, Dad continued to act like he had a legitimate reason for writing these numbers on the bottom of his socks. As I began to howl like a hyena on laughing gas, convulsing at the completely ludicrous nature of his newest fashion choice, Dad kept trying to explain his line of insanity.

“I’m not making this up!” he said through a wide, mischievous smile. “You mean to tell me you’ve never had discomfort from wearing two socks that weren’t from the same original pair?”

“Dad, I can tell you with one hundred percent certainty that’s never once happened to me,” I answered, still in shock. “I really feel like there are bigger problems in the world right now than uneven socks.”

With his usual sense of expertise in all matters, Dad kept pushing and told me why it made sense to number your socks. In response, I continued to tell him that he was crazy and that he was closer to the nursing home than I had originally thought. Then, to my disbelief, Dad went into his dresser and pulled out the other socks that he had numbered. I laughed hysterically when I realized this wasn’t just a one-pair-trial. Dad had gone into his extensive sock collection and meticulously numbered each pair with thick, black numbers.

There was just no way any of this could be real.

I laughed for hours. And after the laughter, I prayed with every fiber in my being that my friends did not come over and see these numbers on the bottoms of Dad’s socks. I had a hard enough time making friends. I didn’t need my Dad running around explaining the physics of sock fabric to make my social interactions even more infrequent than they already were.

Over the next few years, and to my explicit frustration, Dad’s sock numbering became a ritual as steady as the ocean waves. Every time Dad bought a new pair of socks, he would sit down and number them with a thick, black permanent marker, picking up with the number right where he had left off with his last addition. As more socks were added to the drawer, the number grew and grew. And the more I protested and ridiculed, the bigger the numbers became. Before he knew it, his sock pairs grew into the thirties and forties.

And as the numbers grew, so did my utter confusion. Every time Dad would kick his feet up onto the recliner, I would be staring at a set of “17’s” or “6’s” in my face. I never, ever let it go unnoticed.

“Ah, I see you’ve got the 8’s on tonight,” I’d joke. “Solid choice.” Or “Oh, you going with the 14’s today? Must be feelin’ lucky.”

“Joke all you want,” he’d smugly respond, “but when you’ve got a sweaty left foot and a right foot with frostbite on the same night, you won’t be laughing then.”

“I’ll be sure to let the pigs I’m flying next to know they should be numbering their hoof covers, too,” I’d shoot back.

No matter how much I ridiculed him (which was frequently), and no matter how often Mom would protest about how frustrating it was to have to sort through the laundry while folding to find two 12’s to match up into a ball, Dad continued to fight the good sock fight. He never let our teasing deter him from his battle to eradicate uneven socks from the face of the Earth.

And then, one day, his line of defense hit an all-time low.

Dad and I often found ourselves sitting together in the family room watching episodes of comedic sitcoms like Home Improvement, Everybody Loves Raymond, Seinfeld, and The Office on an endless loop—a tradition I’ve carried on in his absence quite well, if I say so myself. On this particular night, our show of choice was The King of Queens, a recurring favorite in the family room of our humble home. One of our favorite characters on the show was Arthur—the nearly-senile father/father-in-law of Carrie and Doug, who lived in the basement and caused more problems than any one human should. For those who haven’t ever seen the show, Arthur is…completely crazy. He burns down his house using a hot plate and has to move into Doug and Carrie’s home. He screams about…well, absolutely anything. He is “walked” by a neighborhood dog walker, and he creates altercations with anyone who doesn’t give into his ridiculous demands. He completely infuriates Doug with his random obsessions and eccentricities. And in the cold open of the episode Dad and I were watching that night, Arthur walks into the room, sits in the chair, and throws his feet up on the coffee table. Emblazoned upon the bottom of each of his white socks? Bright, flaming-red 4’s.

“Shut up,” I said in complete bewilderment as I stared at the television. Dad began gesticulating towards the screen as he let out a victory shriek that sounded like it came from an other-worldly language.

With the same look of confusion I had the first time I saw it, Doug begins to question Arthur about why his socks have huge numbers on the bottom.

“It’s my new system,” Arthur responds in his usually odd diction. “I label them so I don’t mix them up with my other sets of socks,” as he points to his head to show what a brilliant idea he’s had.

“I TOLD YOU THIS WAS REAL!” Dad had jumped up from the recliner, legitimately shrieking and cackling with excitement. “I’M VINDICATED!”

“Dad,” I said, still feeling like I was living in an episode of The Twilight Zone, “you realize you’re identifying with the crazy guy on a television sitcom, right? That’s probably not a good thing!”

He didn’t care, because just seeing that he wasn’t the only person in the world—real or fictitious—who thought numbering socks was a brilliant idea gave him all the security he needed to keep on keeping on. He had proved the naysayers wrong with the opening minute of a family sitcom.

Still confused, Doug begins to ask Arthur why he’s doing this, which opens up a whole new line of ridiculous reasoning Arthur describes as “Toe Memory.” He explains that over time, a sock either evolves into a left sock or a right sock, taking on the unique shape and curvature of each respective foot. Wearing a sock that has evolved into a left sock on your right foot is enough to drive you mad, Arthur argues. All the while, Dad is nodding along as Arthur explains the method behind his madness. I couldn’t believe what I was seeing and hearing.

“How do the 4’s tell you which one is a right and which one is a left?” Doug says.

“Look, Douglas,” Arthur responds as he raises his voice, “my system has its flaws. But I’ve come at this from every angle and believe me, there is no better way!”

“Mhmm, mhmm…” Doug says as he falls back into the couch, getting ready to drop a bombshell on Arthur. “Or you could just label every sock with an L or an R.”

“Well, THERE GOES MY FUNDAY!” Arthur shrieks as he jumps up from the chair and retreats to his basement dwelling.

“Again, Dad,” I said as we laughed at what we were watching, “you want Arthur Spooner to be your co-defendant on this one?!”

Dad and I laughed about that moment for a long, long time; but something even scarier happened. Dad actually began to realize that his system, like Arthur’s, was also flawed! Like Arthur, although the socks were numbered, he hadn’t been able to crack the whole left/right conundrum.

That’s when the two-component sock labeling system was born, adding fuel to my critical fire.

If my shock could’ve grown more, it did. Now, not only was Dad labeling each pair of socks with a number; each sock within the pair was also being labeled with an “L” or “R” after the number. From this point forward, within the set of 15’s (for example), there would be a “15L” and a “15R”.

Insanity had reached a new peak, and it was the two-component sock labeling system.

For the rest of his life, any time I saw those black, hand-drawn number/letter combos on the bottoms of his socks, I made fun of Dad. And every time I made fun of him, he would always shoot back with a witty (and completely insane) retort. No matter how much teasing occurred, he never quit. His resolve was steeled with every insult, every jab. Until the day he died, every sock he bought was appropriately paired and labeled, much to my chagrin.

His feet were always warm, and my heart was always full of laughter. In the end, I guess it was a win-win.

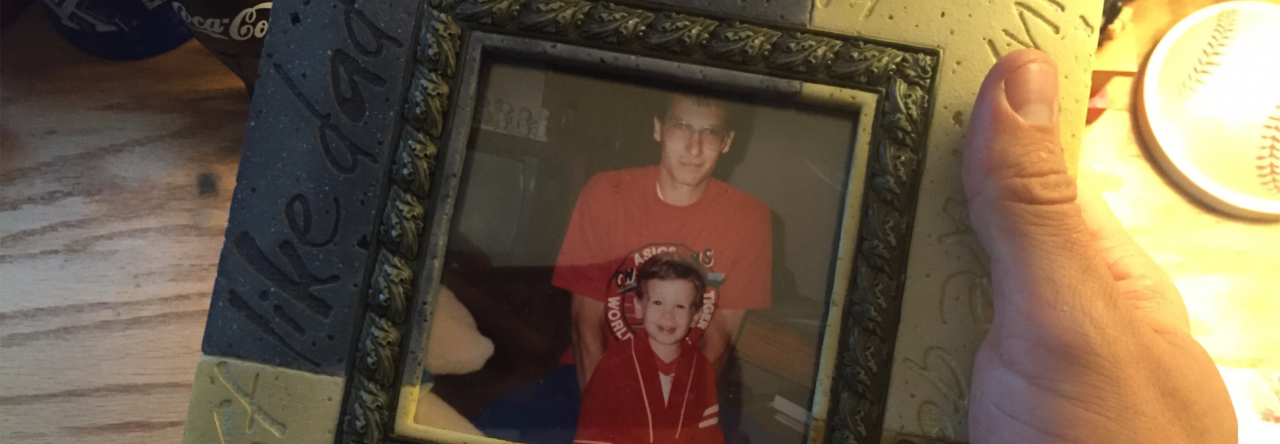

My Dad had a lot of those quirky little idiosyncrasies: numbering his socks, weaving his extension cords into perfect chains to prevent tangling, writing on graph paper to make his already-precise, all-capital printing even more precise than it already was. When he was alive, those peculiar behaviors were sometimes perplexing, sometimes endearing, sometimes annoying, but always seemingly mundane. Now that he is gone, I miss those little ticks in his behaviors and personalities. I miss how way he always cut apples into two large halves while still extracting the core and preserving all of the fruit. I miss the way he’d organize tools or clean his truck. And yes, I even miss his sock numbering, ridiculous as it may have been. I miss every single thing about my Dad, but as much as I miss the big and memorable moments, I think I miss the little quirks more because I took them for granted while he was alive.

And sadly, but also beautifully and completely against my will, I realize how I’m becoming more and more like him—no matter how hard I might fight against those quirks.

The other day, a crazy thing happened that reminded me how much I missed him while completely terrifying me. I was putting on one of my black ankle-cut socks to head to the gym. (I’m a bit ashamed to admit that during the winters, I’ve started wearing those hideous, wool socks that Dad used to wear—he really was on to something with his choice in foot coverings.) Nonetheless, on this day, as I was putting on my gym socks, I was running through what clothes I was going to wear to the gym in my head. I put the left sock on, and before I could even stop my internal dialogue from churning, I felt the phrase cross into my line of thought:

“This sock feels kind of weird. Maybe I should put it on my right foot instead.”

The shock of what I just thought hit me hard. My eyes were as big as the 2’s that had once been written on the bottom of my Dad’s socks. I had to stop getting dressed and collect my thoughts before I started hyperventilating. There was no way, no way Dad could be right about this one. It just wasn’t possible. And as I sat there on the edge of the bed freaking out and questioning everything I’ve ever believed about socks, I could hear Dad’s laugh. I could see him looking down from heaven and laughing hysterically, pointing and shouting, “I told you, Bub!”

And after the shock wore off, I laughed through a few tears as I realized how much I missed his weirdness and everything else that made him so real and so special.

I’m glad that the nature of my Dad’s death from suicide has not prevented my ability to appreciate those happier moments. I’m glad that the questions I have about why Dad died on that July morning in 2013 haven’t completely darkened the beautiful, vivid intricacies of his personality that made him so exceptional and unique. I’m glad that I can still remember the good days and moments in spite of the one bad day that ended his life. I’m glad that I can look back on numbered socks and laugh, because his death has taken enough from me and from all of us who loved him. I’m glad that I can look back at my Dad and remember him for the man he was for 50 years, not just the man he was on that last, painful day. I’m glad that I can still laugh with him and reminisce on those mundane yet elegant memories. I am really looking forward to the day when I can laugh with him about those moments again.

And along with those streets paved with gold, I hope that Heaven is home to socks that no longer wear thin unequally.

Dad, I still laugh when I think about your sock-numbering-insanity. I still smile when I think about all of the times I would rib you about putting numbers and letters on all your socks, and I can’t believe I’m saying this, but I really miss seeing those numbers. More importantly, I miss seeing you kick your feet up on the recliner in our family room. I miss laughing with you while we watched television together. I miss hearing you snore as you napped in the recliner wearing your lucky pair of 14’s, and I miss those moments of levity and peace that we were able to build in our family home. Your personality was a force for good in our family, Dad. Through the big moments and the little, everyday behaviors, you made our home a better place. You made all of us better people—even though you couldn’t get anyone to join in on your sock-numbering. Those beautiful little moments gave life vivid color. You gave us entertainment and joy in seemingly simple ways, and I’m glad that I remember the quirks of your personality. I’m glad that I can focus on the simplistic beauty of your life without obsessing over its tragic end. Dad, thank you for always making life more beautiful. Thank you for giving to all of us more than we could have ever given you in return. I miss you tremendously. I miss you each and every day. And if I get to Heaven and you have numbered socks on, I seriously don’t know what I’m going to say to you. I’m sure you’ll keep me on my non-numbered toes. But until I can tease you again, seeya Bub.

Dad, I still laugh when I think about your sock-numbering-insanity. I still smile when I think about all of the times I would rib you about putting numbers and letters on all your socks, and I can’t believe I’m saying this, but I really miss seeing those numbers. More importantly, I miss seeing you kick your feet up on the recliner in our family room. I miss laughing with you while we watched television together. I miss hearing you snore as you napped in the recliner wearing your lucky pair of 14’s, and I miss those moments of levity and peace that we were able to build in our family home. Your personality was a force for good in our family, Dad. Through the big moments and the little, everyday behaviors, you made our home a better place. You made all of us better people—even though you couldn’t get anyone to join in on your sock-numbering. Those beautiful little moments gave life vivid color. You gave us entertainment and joy in seemingly simple ways, and I’m glad that I remember the quirks of your personality. I’m glad that I can focus on the simplistic beauty of your life without obsessing over its tragic end. Dad, thank you for always making life more beautiful. Thank you for giving to all of us more than we could have ever given you in return. I miss you tremendously. I miss you each and every day. And if I get to Heaven and you have numbered socks on, I seriously don’t know what I’m going to say to you. I’m sure you’ll keep me on my non-numbered toes. But until I can tease you again, seeya Bub.

“Even in laughter a heart may be sad, and joy may end in grief.” Proverbs 14:13 (HCSB)

Dad, There are many moments when I think about your last day here on Earth and wish, desperately, that it would have ended differently. I can’t even begin to fathom or understand the pain and despair you must have felt in those moments. You loved life so much, which shows me how much hopelessness you were experiencing to believe that life wasn’t worth living any longer. I cry when I think of those moments because, Dad, you were so loved by so many. You should be here, right now, living life and loving every step along the way. You deserved that type of hope. But Dad, even in the midst of the pain you probably felt in those last few minutes, I’m grateful that you aren’t experiencing that pain any longer. You now reside in an everlasting paradise of joy, hope, comfort, and eternal fellowship with the God who loves you and loves all of us. Dad, I wake up every day wishing I could see you again. I picture your face and I can see your smile, and I just want you to be back here with us. But because you’re not, I’ll take comfort in the fact that I know where you are. And that I know I’ll see you again. I love you Dad. Until that wonderful reunion, seeya Bub.

Dad, There are many moments when I think about your last day here on Earth and wish, desperately, that it would have ended differently. I can’t even begin to fathom or understand the pain and despair you must have felt in those moments. You loved life so much, which shows me how much hopelessness you were experiencing to believe that life wasn’t worth living any longer. I cry when I think of those moments because, Dad, you were so loved by so many. You should be here, right now, living life and loving every step along the way. You deserved that type of hope. But Dad, even in the midst of the pain you probably felt in those last few minutes, I’m grateful that you aren’t experiencing that pain any longer. You now reside in an everlasting paradise of joy, hope, comfort, and eternal fellowship with the God who loves you and loves all of us. Dad, I wake up every day wishing I could see you again. I picture your face and I can see your smile, and I just want you to be back here with us. But because you’re not, I’ll take comfort in the fact that I know where you are. And that I know I’ll see you again. I love you Dad. Until that wonderful reunion, seeya Bub.  Reverend Dan Walters

Reverend Dan Walters

Most nights, Lucy would make her way into my room, usually at just the right moment. She would push the door open with her snout, tail wagging feverishly, and climb up onto the bed. After arriving, Lucy would place a paw on either side of my shoulders and lick my face until I begged her to stop. A twin mattress doesn’t provide much room for a grown man and a 70-pound dog, but Lucy made a way. She would curl up alongside me and lay her head across my chest. And in those moments, even though she was a dog and might not have understood human emotions, Lucy soothed my heart in ways I’ll never be able to describe.

Most nights, Lucy would make her way into my room, usually at just the right moment. She would push the door open with her snout, tail wagging feverishly, and climb up onto the bed. After arriving, Lucy would place a paw on either side of my shoulders and lick my face until I begged her to stop. A twin mattress doesn’t provide much room for a grown man and a 70-pound dog, but Lucy made a way. She would curl up alongside me and lay her head across my chest. And in those moments, even though she was a dog and might not have understood human emotions, Lucy soothed my heart in ways I’ll never be able to describe. Lucy also helped soothe my pain because of the fact that

Lucy also helped soothe my pain because of the fact that  It was that puppy companionship, along with many other wonderful people and things, that helped me heal and grieve my Dad properly. I had so many wonderful people who knew exactly how to minister to me after losing Dad—my Mom, my grandparents, my church family, my friends, my coworkers, my neighbors, and even complete strangers. I also found little things I could do to help me grieve for Dad properly—things to help me forget about the pain of losing him. I read my Bible frequently in my study. I wrote feverishly—some of those scrawlings eventually turning into the foundations of this project. I exercised frequently, although the Ryan Gosling physique (or anything

It was that puppy companionship, along with many other wonderful people and things, that helped me heal and grieve my Dad properly. I had so many wonderful people who knew exactly how to minister to me after losing Dad—my Mom, my grandparents, my church family, my friends, my coworkers, my neighbors, and even complete strangers. I also found little things I could do to help me grieve for Dad properly—things to help me forget about the pain of losing him. I read my Bible frequently in my study. I wrote feverishly—some of those scrawlings eventually turning into the foundations of this project. I exercised frequently, although the Ryan Gosling physique (or anything  remotely close) still eluded me.

remotely close) still eluded me. On other days, I would let Lucy hop up into the passenger seat of my car and we would take a drive together. Lucy really enjoyed driving around town, and her excitement created smiles and laughter in neighboring vehicles as she sat calmly next to me in the car with her seatbelt on. I would make a conscious effort to go through drive-thrus with Lucy to show her off to anyone who would remark about what a cute pup she was. She was cute—she deserved the adoration!

On other days, I would let Lucy hop up into the passenger seat of my car and we would take a drive together. Lucy really enjoyed driving around town, and her excitement created smiles and laughter in neighboring vehicles as she sat calmly next to me in the car with her seatbelt on. I would make a conscious effort to go through drive-thrus with Lucy to show her off to anyone who would remark about what a cute pup she was. She was cute—she deserved the adoration! It’s hard to describe, but in those moments, Lucy would nervously saunter up to my side when she knew I was hurting. It was like she understood that she needed to be by my side. And that’s what she would do. She would hop on the couch and lay her head in my lap. She would leave all her toys (and boy did she love toys) to just lay near me. I would gently pat her head or her back, and slowly, her presence would help me escape from that immediate terror. She did more for me in those moments than I could ever tell her. Lucy showed me what it meant to be “man’s best friend.”

It’s hard to describe, but in those moments, Lucy would nervously saunter up to my side when she knew I was hurting. It was like she understood that she needed to be by my side. And that’s what she would do. She would hop on the couch and lay her head in my lap. She would leave all her toys (and boy did she love toys) to just lay near me. I would gently pat her head or her back, and slowly, her presence would help me escape from that immediate terror. She did more for me in those moments than I could ever tell her. Lucy showed me what it meant to be “man’s best friend.” That sadness would often give way to anger. Lucy’s death was completely avoidable and unnecessary. A groomer that we had trusted—a groomer who knew the despair of our family situation—had cared so little about our family and our pet that he let her die as a result of his negligence. As you might imagine, the story of Lucy’s death attracted the attention of a local news station.

That sadness would often give way to anger. Lucy’s death was completely avoidable and unnecessary. A groomer that we had trusted—a groomer who knew the despair of our family situation—had cared so little about our family and our pet that he let her die as a result of his negligence. As you might imagine, the story of Lucy’s death attracted the attention of a local news station.  I bought a pound of the licorice dogs (and a few other goodies, of course), and the second Paige and I got into the truck, I opened the bags and started chowing down. I tasted the licorice, and it brought back all the memories of Lucy and how funny it was to watch her eat licorice. I began recounting the story to Paige, and before I knew it, I was flashing back to the moment I lost her. All of the sadness and despair of her death was as real then as it was on the day I lost her—all because of a piece of licorice that reminded me of her.

I bought a pound of the licorice dogs (and a few other goodies, of course), and the second Paige and I got into the truck, I opened the bags and started chowing down. I tasted the licorice, and it brought back all the memories of Lucy and how funny it was to watch her eat licorice. I began recounting the story to Paige, and before I knew it, I was flashing back to the moment I lost her. All of the sadness and despair of her death was as real then as it was on the day I lost her—all because of a piece of licorice that reminded me of her. On occasion, I’ll put on that

On occasion, I’ll put on that  Dad, I need to tell you that I’m sorry and that I’m thankful. I’m sorry that I acted so stubborn when you chose to bring Lucy into our family. I’m sorry that I acted like a “little jerk” (your words…and mine) when you were just doing what was best for us. Ultimately, I’m so grateful that you chose Lucy. I’m grateful that you raised her and trained her and taught her to be a fun, family dog. We had no idea how much we were going to need her fun-loving, thoughtful companionship after losing her. In a way, I feel like Lucy carried on so many of your personality traits after you were gone. She was a constant reminder of the zest and excitement you had for life. She was there to help us grieve in so many ways after you left us. I think Lucy was your angel here on Earth for us. I think that she was your way of telling us that life, even when it’s painful, can still have a lot of joy and happiness. Losing her was like losing you all over again. It was as if another piece of you—a very important piece—was gone forever. But Dad, I know that we will never lose you entirely. Your memory will always live on in our hearts and in our minds because you made such an indelible mark on all of us. Dad, thank you for Lucy. Thank you for teaching her to love us when we needed it most. Although I miss you both dearly, I hope that you are together again in heaven—and I hope there are plenty of Frisbees to toss. You deserve paradise, Dad. You deserve the greatest things that God can offer, and I can’t wait to experience that joy alongside you. Until that day where you and I are together again in a life that knows no end, seeya Bub.

Dad, I need to tell you that I’m sorry and that I’m thankful. I’m sorry that I acted so stubborn when you chose to bring Lucy into our family. I’m sorry that I acted like a “little jerk” (your words…and mine) when you were just doing what was best for us. Ultimately, I’m so grateful that you chose Lucy. I’m grateful that you raised her and trained her and taught her to be a fun, family dog. We had no idea how much we were going to need her fun-loving, thoughtful companionship after losing her. In a way, I feel like Lucy carried on so many of your personality traits after you were gone. She was a constant reminder of the zest and excitement you had for life. She was there to help us grieve in so many ways after you left us. I think Lucy was your angel here on Earth for us. I think that she was your way of telling us that life, even when it’s painful, can still have a lot of joy and happiness. Losing her was like losing you all over again. It was as if another piece of you—a very important piece—was gone forever. But Dad, I know that we will never lose you entirely. Your memory will always live on in our hearts and in our minds because you made such an indelible mark on all of us. Dad, thank you for Lucy. Thank you for teaching her to love us when we needed it most. Although I miss you both dearly, I hope that you are together again in heaven—and I hope there are plenty of Frisbees to toss. You deserve paradise, Dad. You deserve the greatest things that God can offer, and I can’t wait to experience that joy alongside you. Until that day where you and I are together again in a life that knows no end, seeya Bub.

From the moment she came home, Lucy was impossible to resist. I have a weak-constitution for puppy cuteness, and Lucy melted my defenses rather quickly. Airedale terriers are adorable puppies. What will eventually grow into a 60 or 70-pound dog starts out as an eight-pound ball of fur with a shortened snout and gangly legs. Lucy looked like most Airedale pups I had seen in photographs, but there was one defining characteristic that was different. Lucy had a tiny little white patch of fur right on the middle of her chest. I had never seen an Airedale with any color fur other than black and brown. Immediately, she was different from the rest; and the more I got to know her, the more wonderfully different I discovered she was.

From the moment she came home, Lucy was impossible to resist. I have a weak-constitution for puppy cuteness, and Lucy melted my defenses rather quickly. Airedale terriers are adorable puppies. What will eventually grow into a 60 or 70-pound dog starts out as an eight-pound ball of fur with a shortened snout and gangly legs. Lucy looked like most Airedale pups I had seen in photographs, but there was one defining characteristic that was different. Lucy had a tiny little white patch of fur right on the middle of her chest. I had never seen an Airedale with any color fur other than black and brown. Immediately, she was different from the rest; and the more I got to know her, the more wonderfully different I discovered she was. Dad sat the blanket bundle down on his lap, and Lucy poked her head out from the blanket mound and peered around our family room. She looked straight at me with her dark eyes, and when she made her way down onto the carpet and slowly meandered towards me, I knew that I was done. My resistance would have to fall, because this pup was just too cute. With the pain of losing Willow momentarily fading, I reached down and scooped Lucy into my arms. For the rest of the night, she and I spent our time on the couch as she adjusted to her new surroundings. A few times, I glanced at Mom and Dad and saw them giving one another that familiar “I told you he’d cave” look. I tried my best to not let them get any satisfaction from defying my gutless order to not bring home another family dog, but it was useless.

Dad sat the blanket bundle down on his lap, and Lucy poked her head out from the blanket mound and peered around our family room. She looked straight at me with her dark eyes, and when she made her way down onto the carpet and slowly meandered towards me, I knew that I was done. My resistance would have to fall, because this pup was just too cute. With the pain of losing Willow momentarily fading, I reached down and scooped Lucy into my arms. For the rest of the night, she and I spent our time on the couch as she adjusted to her new surroundings. A few times, I glanced at Mom and Dad and saw them giving one another that familiar “I told you he’d cave” look. I tried my best to not let them get any satisfaction from defying my gutless order to not bring home another family dog, but it was useless. And from that moment on, I don’t think I ever quit loving Lucy. Even if my stubborn pride wouldn’t let me admit it.

And from that moment on, I don’t think I ever quit loving Lucy. Even if my stubborn pride wouldn’t let me admit it. Lucy had that in abundance. Lucy’s calm demeanor during the first 24 hours of her life in my family was a well-executed mirage delivered by a sneaky infiltrator. When I came home on Lucy’s second day in the Bradshaw house, the docile, pleasant pup that I had left that morning was replaced with a rambunctious, mischievous, four-legged fur-covered peddler of destruction. When I came home that day, my poor Mother looked like she had barely survived a hurricane. She looked at me with a frazzled exasperation as Lucy, with toys strewn all across our normally-clean family room, bounced and barked and bolted to every corner of the house. She was worse than a baby because she was faster. I couldn’t believe she had fooled us! Lucy had spunk—and a whole lot of it.

Lucy had that in abundance. Lucy’s calm demeanor during the first 24 hours of her life in my family was a well-executed mirage delivered by a sneaky infiltrator. When I came home on Lucy’s second day in the Bradshaw house, the docile, pleasant pup that I had left that morning was replaced with a rambunctious, mischievous, four-legged fur-covered peddler of destruction. When I came home that day, my poor Mother looked like she had barely survived a hurricane. She looked at me with a frazzled exasperation as Lucy, with toys strewn all across our normally-clean family room, bounced and barked and bolted to every corner of the house. She was worse than a baby because she was faster. I couldn’t believe she had fooled us! Lucy had spunk—and a whole lot of it. But with Lucy, it was different from the start. She was immediately allowed onto the couch—and I was shocked! And then, the unthinkable happened; Mom actually let Lucy sleep in the bed with her! What world was I living in?! Who had abducted my Mom and who was this woman that now gladly beckoned the dog onto the furniture?

But with Lucy, it was different from the start. She was immediately allowed onto the couch—and I was shocked! And then, the unthinkable happened; Mom actually let Lucy sleep in the bed with her! What world was I living in?! Who had abducted my Mom and who was this woman that now gladly beckoned the dog onto the furniture? When Lucy was little, I used to carry her around the house quite often. And unlike most dogs, she really enjoyed being carried! After a little while, it got more and more difficult to carry her around as she continued to grow. And by the time she reached 40 pounds, our little puppy, who I affectionately called “Monkey”, was a bit to heavy to carry with one arm. So I did what any normal person would do.

When Lucy was little, I used to carry her around the house quite often. And unlike most dogs, she really enjoyed being carried! After a little while, it got more and more difficult to carry her around as she continued to grow. And by the time she reached 40 pounds, our little puppy, who I affectionately called “Monkey”, was a bit to heavy to carry with one arm. So I did what any normal person would do. I would actually pick Lucy up by her front legs and toss them over my shoulder. Then, Lucy would wrap her hind legs around my waist, and I would comfortably carry her around as she nuzzled her snout on my shoulder. Looking back, it’s the most ridiculous thing I could ever imagine doing as a dog owner.

I would actually pick Lucy up by her front legs and toss them over my shoulder. Then, Lucy would wrap her hind legs around my waist, and I would comfortably carry her around as she nuzzled her snout on my shoulder. Looking back, it’s the most ridiculous thing I could ever imagine doing as a dog owner. Thankfully, my Dad, our dog-whisperer-in-residence, was there to take care of most of the discipline and direction when we first got Lucy. My Dad loved working with animals, even when the animals weren’t easy to work with. I think he saw teaching pets as a challenge that he wanted to conquer, and he had a way of showing love through firmness. Quickly and efficiently, Lucy was housebroken and learning how to sit, lay down, and yes…play hide and seek with Dad. My Dad had a special talent, and we all benefited from it.

Thankfully, my Dad, our dog-whisperer-in-residence, was there to take care of most of the discipline and direction when we first got Lucy. My Dad loved working with animals, even when the animals weren’t easy to work with. I think he saw teaching pets as a challenge that he wanted to conquer, and he had a way of showing love through firmness. Quickly and efficiently, Lucy was housebroken and learning how to sit, lay down, and yes…play hide and seek with Dad. My Dad had a special talent, and we all benefited from it. Dad, being a playful guy, did everything with Lucy. If he was home, he wanted to be near her. If he had a bonfire in the backyard, Lucy was with him. If he was eating dinner, she was patiently waiting for a scrap nearby. If he was taking a nap, she was on the couch cuddled next to him. There were hour-long walks to the park, trips to the dog beach at Hueston Woods, and countless other memories that the two of them created together. They are memories filled with laughter and companionship, but joy more than anything else.

Dad, being a playful guy, did everything with Lucy. If he was home, he wanted to be near her. If he had a bonfire in the backyard, Lucy was with him. If he was eating dinner, she was patiently waiting for a scrap nearby. If he was taking a nap, she was on the couch cuddled next to him. There were hour-long walks to the park, trips to the dog beach at Hueston Woods, and countless other memories that the two of them created together. They are memories filled with laughter and companionship, but joy more than anything else. And Lucy was there to help me—and all of us—find a small ray of light in the midst of the dark clouds that enveloped our family. Lucy—sweet Lucy—would help to save us as best she could.

And Lucy was there to help me—and all of us—find a small ray of light in the midst of the dark clouds that enveloped our family. Lucy—sweet Lucy—would help to save us as best she could.

Every single day is difficult—all 1,827 of them; but every single year, July 24 is a date that stares at me from the calendar. It looms in the distance for months, and when it passes, I always breathe a sigh of relief that it’s come and gone. But I know, deep down, that it’s coming again. It will always be there. No particular July 24 has been more or less difficult—just different. But because of the nice, round number, this one feels like a milestone. A milestone I wish I didn’t have to reach.

Every single day is difficult—all 1,827 of them; but every single year, July 24 is a date that stares at me from the calendar. It looms in the distance for months, and when it passes, I always breathe a sigh of relief that it’s come and gone. But I know, deep down, that it’s coming again. It will always be there. No particular July 24 has been more or less difficult—just different. But because of the nice, round number, this one feels like a milestone. A milestone I wish I didn’t have to reach. But guess what? No amount of procrastination could stop that date from coming. No amount of denial could stop me from thinking about what this day represents. This day would come—and yes, it would eventually pass—but the second it did, the clock just begin counting down towards another unfortunate milestone. The next Christmas. The next birthday. The next Father’s Day.

But guess what? No amount of procrastination could stop that date from coming. No amount of denial could stop me from thinking about what this day represents. This day would come—and yes, it would eventually pass—but the second it did, the clock just begin counting down towards another unfortunate milestone. The next Christmas. The next birthday. The next Father’s Day. On the other side of all that grief and sadness, there will be an everlasting love made whole again. On the other side of that grief, there will be a man whom I recognize, smiling and welcoming me into his arms. In that moment, I’ll love never having to say “seeya, Bub” again. That day is coming, although it’s very far off.

On the other side of all that grief and sadness, there will be an everlasting love made whole again. On the other side of that grief, there will be a man whom I recognize, smiling and welcoming me into his arms. In that moment, I’ll love never having to say “seeya, Bub” again. That day is coming, although it’s very far off. Dad, I cry so much when I think that it’s been five years since you and I last talked. Sometimes, those tears are unstoppable. We never even went five days in this life without talking to one another. Dad, it really has felt like an eternity—but sometimes your memory is so real and so vivid that it seems like it was just yesterday when we lost you. But I know the real time. I know that it’s been five whole years since we’ve been able to be in your presence. And life simply isn’t the same without you. We all cling to your memory. We marvel at the things you built and the way you provided for our family. We laugh about the funny things you did to make life more fun. But I also weep when I think about how much life you had left to live. Dad, I’m so sorry that you were sick. I feel horrible that we couldn’t do more to help you find the cure you deserved. I’m sorry that you were robbed of the life you deserved to enjoy. I’ve felt so much guilt in losing you Dad. I know that you don’t want me to feel this way, but I just wish there was more I could have done. You deserved that, Dad. You deserved more, because you gave everything. As painful as these five years have been, Dad, I find peace in the truth of Eternity. I find comfort knowing that you are enjoying God’s eternal glory in a paradise that I can’t even begin to fathom. Dad, thank you for watching over me for these past five years. Thank you for never giving up on me—both in this life, and in the next. Thank you for giving me a lifetime of memories and an example of what fatherhood should be. I love you, Dad. I always did, and I always will. Thank you for loving me back. Until I see you again, seeya Bub.

Dad, I cry so much when I think that it’s been five years since you and I last talked. Sometimes, those tears are unstoppable. We never even went five days in this life without talking to one another. Dad, it really has felt like an eternity—but sometimes your memory is so real and so vivid that it seems like it was just yesterday when we lost you. But I know the real time. I know that it’s been five whole years since we’ve been able to be in your presence. And life simply isn’t the same without you. We all cling to your memory. We marvel at the things you built and the way you provided for our family. We laugh about the funny things you did to make life more fun. But I also weep when I think about how much life you had left to live. Dad, I’m so sorry that you were sick. I feel horrible that we couldn’t do more to help you find the cure you deserved. I’m sorry that you were robbed of the life you deserved to enjoy. I’ve felt so much guilt in losing you Dad. I know that you don’t want me to feel this way, but I just wish there was more I could have done. You deserved that, Dad. You deserved more, because you gave everything. As painful as these five years have been, Dad, I find peace in the truth of Eternity. I find comfort knowing that you are enjoying God’s eternal glory in a paradise that I can’t even begin to fathom. Dad, thank you for watching over me for these past five years. Thank you for never giving up on me—both in this life, and in the next. Thank you for giving me a lifetime of memories and an example of what fatherhood should be. I love you, Dad. I always did, and I always will. Thank you for loving me back. Until I see you again, seeya Bub.

Dad, There have been so many times when I’ve thought about the fear you must have experienced in your life. You were always my Superman—that strong rock and foundation in my life when everything else seemed dangerous. On the outside, you were always “Mr. Fix It,” and I know it bothered you that you couldn’t solve your own struggles with depression. On the surface, you always held everything together—for your family, for your friends, and especially for Mom and I. But Dad, I wish I could have told you that your struggles with mental illness were never a disappointment to any of us. We never thought less of you when you battled with your depression. Sick or healthy, we always loved you and wanted to be near you. You were never a failure to us, Dad. You never failed us, and I wish you had known that more. I am afraid of doing life without you. I have a fear that I can’t do what God is calling me to do to tell your story. But I know that He is with me, and I know that you are with me. I know that you are watching down and pushing me and urging me onward, just as you always did when you were here with us. We all miss you, Dad. We will never stop missing you. You never let me down, and I can’t wait to tell you that in person. Until that day, seeya Bub.

Dad, There have been so many times when I’ve thought about the fear you must have experienced in your life. You were always my Superman—that strong rock and foundation in my life when everything else seemed dangerous. On the outside, you were always “Mr. Fix It,” and I know it bothered you that you couldn’t solve your own struggles with depression. On the surface, you always held everything together—for your family, for your friends, and especially for Mom and I. But Dad, I wish I could have told you that your struggles with mental illness were never a disappointment to any of us. We never thought less of you when you battled with your depression. Sick or healthy, we always loved you and wanted to be near you. You were never a failure to us, Dad. You never failed us, and I wish you had known that more. I am afraid of doing life without you. I have a fear that I can’t do what God is calling me to do to tell your story. But I know that He is with me, and I know that you are with me. I know that you are watching down and pushing me and urging me onward, just as you always did when you were here with us. We all miss you, Dad. We will never stop missing you. You never let me down, and I can’t wait to tell you that in person. Until that day, seeya Bub. Reverend Dan Walters

Reverend Dan Walters

When I was extremely young, my family never took beach vacations. To this day, I’m not sure why because we all loved the beach so much. My very first time seeing the ocean was on a family trip to Panama City, Florida as an eighth grader. Our entire family (grandparents and cousins included) spent a wonderful week on the Gulf Coast, and I remember the momentous nature of that trip, even as a middle schooler. A 12-hour, multi-day car ride had finally concluded, and my Mom and Dad walked me out towards the ocean once we arrived. With my parents, I saw the ocean for the very first time and I got to experience its magnitude. I got to touch sand, and taste saltwater, and splash in the world’s largest pool. Even as a young kid, I appreciated the significance of this experience.

When I was extremely young, my family never took beach vacations. To this day, I’m not sure why because we all loved the beach so much. My very first time seeing the ocean was on a family trip to Panama City, Florida as an eighth grader. Our entire family (grandparents and cousins included) spent a wonderful week on the Gulf Coast, and I remember the momentous nature of that trip, even as a middle schooler. A 12-hour, multi-day car ride had finally concluded, and my Mom and Dad walked me out towards the ocean once we arrived. With my parents, I saw the ocean for the very first time and I got to experience its magnitude. I got to touch sand, and taste saltwater, and splash in the world’s largest pool. Even as a young kid, I appreciated the significance of this experience. After a really, really long drive, my family finally arrived to our condo in Gulf Shores. Shortly after arriving, I think we all knew then that we had found our family vacation spot. There was something about it that made us feel like we were home.

After a really, really long drive, my family finally arrived to our condo in Gulf Shores. Shortly after arriving, I think we all knew then that we had found our family vacation spot. There was something about it that made us feel like we were home. As I’ve written before, Dad was a tremendous athlete. And also as I’ve written before, I was a horrible one. But Dad never let my lack of athleticism curb an opportunity to play. At the beach, Dad and I could throw a frisbee for hours—as long as the wind cooperated. We would warm up close to one another and gradually step back as we threw until we would finally hit a point where we had to wind our torsos like a corkscrew to get the frisbee to sail over the white sand. Dad and I would leap and dive into the sand to catch a frisbee—his leaps and dives always significantly more graceful than mine—and we would yell at each other for not being able to properly hit our target. “Did you actually expect me to catch that?!” we would yell across the beach at one another. “You’re gonna kill a kid with that thing if you don’t learn how to throw it!”

As I’ve written before, Dad was a tremendous athlete. And also as I’ve written before, I was a horrible one. But Dad never let my lack of athleticism curb an opportunity to play. At the beach, Dad and I could throw a frisbee for hours—as long as the wind cooperated. We would warm up close to one another and gradually step back as we threw until we would finally hit a point where we had to wind our torsos like a corkscrew to get the frisbee to sail over the white sand. Dad and I would leap and dive into the sand to catch a frisbee—his leaps and dives always significantly more graceful than mine—and we would yell at each other for not being able to properly hit our target. “Did you actually expect me to catch that?!” we would yell across the beach at one another. “You’re gonna kill a kid with that thing if you don’t learn how to throw it!” And at the beach, Dad never played it safe. More than anything, I think Dad and I probably got the most enjoyment of our daily game of “See Who Can Swim the Furthest Out from the Shore and Make Mom Freak Out the Most” (catchy, no?). Much to my Mom’s displeasure, Dad and I were notorious for jumping into the water and swimming straight ahead until our arms gave out. The water would grow colder and colder the further we would swim, and periodically Dad would stick his arms high above his head and straight-dive down to see if he could still touch the bottom. If he could, we still weren’t out far enough. All the while, my poor Mother would sit anxiously in her beach chair watching our bobbing heads grow smaller and smaller in the waves. The best version of the game was on the beaches where there were life guards on duty, and in those scenarios, we tried to see how loud we could get them to blow their whistles at us! We knew we were really killing the game if we could swim far enough to encounter a deeper sandbar, and if we did, we would sit out on the sandbar and rest until it was time to swim back in. Dad would wave to Mom on occasion from the depths of the mighty ocean, and it was amazing how peaceful the deep ocean water can be. All the ambient noises of the beach fade away when you’re that far out (you especially can’t hear life guard whistles or motherly-shrieks).

And at the beach, Dad never played it safe. More than anything, I think Dad and I probably got the most enjoyment of our daily game of “See Who Can Swim the Furthest Out from the Shore and Make Mom Freak Out the Most” (catchy, no?). Much to my Mom’s displeasure, Dad and I were notorious for jumping into the water and swimming straight ahead until our arms gave out. The water would grow colder and colder the further we would swim, and periodically Dad would stick his arms high above his head and straight-dive down to see if he could still touch the bottom. If he could, we still weren’t out far enough. All the while, my poor Mother would sit anxiously in her beach chair watching our bobbing heads grow smaller and smaller in the waves. The best version of the game was on the beaches where there were life guards on duty, and in those scenarios, we tried to see how loud we could get them to blow their whistles at us! We knew we were really killing the game if we could swim far enough to encounter a deeper sandbar, and if we did, we would sit out on the sandbar and rest until it was time to swim back in. Dad would wave to Mom on occasion from the depths of the mighty ocean, and it was amazing how peaceful the deep ocean water can be. All the ambient noises of the beach fade away when you’re that far out (you especially can’t hear life guard whistles or motherly-shrieks). My Grandpa even told a story at Dad’s funeral about his love for always being the last one up. On occasion, my family would take vacations with our extended family, which included my Grandpa Vern, Grandma Sharon, my Uncle Lee, my Aunt Beth, and my two cousins Jake and Megan. Those were always wonderful vacations, and every day, my Grandpa and my Dad were always the last ones up to the condo. But even my Grandpa couldn’t hang with my Dad.

My Grandpa even told a story at Dad’s funeral about his love for always being the last one up. On occasion, my family would take vacations with our extended family, which included my Grandpa Vern, Grandma Sharon, my Uncle Lee, my Aunt Beth, and my two cousins Jake and Megan. Those were always wonderful vacations, and every day, my Grandpa and my Dad were always the last ones up to the condo. But even my Grandpa couldn’t hang with my Dad. Standing there at the beach, I told Steve how much I missed my Dad. I really didn’t have to say anything, because Steve knew—and he was experiencing the grief himself. Steve had been tremendously close with my entire family, and my Dad treated him just like he would treat his own son. Instead of only crying, though, I was able to share tremendous memories and stories of my Dad, telling Steve all about the funny things he had done at the beach on our family vacations. I shared stories about Dad’s Banana Boat expedition, his wave-runner sandbar collision, and how he was always the last one up for dinner. Little by little, the tears were slowly replaced with a smile and laughter. I didn’t miss him any less; I just had a different focus. Instead of focusing on the loss, I was able to focus on his life. Instead of focusing on the time we didn’t have together, I focused on all the wonderful times we did.

Standing there at the beach, I told Steve how much I missed my Dad. I really didn’t have to say anything, because Steve knew—and he was experiencing the grief himself. Steve had been tremendously close with my entire family, and my Dad treated him just like he would treat his own son. Instead of only crying, though, I was able to share tremendous memories and stories of my Dad, telling Steve all about the funny things he had done at the beach on our family vacations. I shared stories about Dad’s Banana Boat expedition, his wave-runner sandbar collision, and how he was always the last one up for dinner. Little by little, the tears were slowly replaced with a smile and laughter. I didn’t miss him any less; I just had a different focus. Instead of focusing on the loss, I was able to focus on his life. Instead of focusing on the time we didn’t have together, I focused on all the wonderful times we did. I spend a lot of time on the beach during dusk as many of the families on the shore will begin to retreat to their condos. And I do this for a simple reason: that’s what Dad would have done. I’ve learned why he loved it so much. As the beach starts to quiet down from a busy day of frivolity and fun, there’s a quiet stillness that begins to wash across the shore. That stillness is enticing and comforting, and it’s in those moments that I often feel closest to God. And I think about how peaceful those moments must have been to a man who struggled with depression. Dad treasured that peace. And now, I treasure the memory of his life during those peaceful moments, and I try to live it out every chance I get.

I spend a lot of time on the beach during dusk as many of the families on the shore will begin to retreat to their condos. And I do this for a simple reason: that’s what Dad would have done. I’ve learned why he loved it so much. As the beach starts to quiet down from a busy day of frivolity and fun, there’s a quiet stillness that begins to wash across the shore. That stillness is enticing and comforting, and it’s in those moments that I often feel closest to God. And I think about how peaceful those moments must have been to a man who struggled with depression. Dad treasured that peace. And now, I treasure the memory of his life during those peaceful moments, and I try to live it out every chance I get. Dad, there has never been a time when I’ve gone to the beach without thinking of you—and there never will be. You made our time at the beach together so memorable, but more than that, you taught me so many important life lessons while we were there. You taught me to slow down and relax. You taught me to soak in God’s beautiful creation. You taught me to be kind to people and get to know them, because God created them, too. You taught me to let go of all the busy things from back home and simply enjoy the life that was in front of me in that moment. I take these lessons with me everywhere I go, but especially when I go to the beach. Even though I’m still able to have fun when I go, it just isn’t the same without you. I miss our throwing sessions, and sometimes I’ll just carry a baseball in my backpack to turn over and over in my hands and think of the time we spent together. I miss trying to see who could swim the furthest out, and watching you beckon me further even when I felt like I couldn’t keep swimming. I miss walking along the shoreline with you and listening to your stories about oil rigs in the distance or planes flying overhead. You had an inquisitive, appreciative spirit for all life had to offer. And more than anything, I miss watching you enjoy those moments on the shore by yourself being the last one up. It’s strange, but sometimes it’s like I look down from the balcony and I can still see you sitting there. Dad, I know you’re still with me. I know that you’re guiding me and watching over me in everything that I do. Thank you for always being my best teacher. Thank you for being a Dad unlike any other. And thank you for always teaching me that the last one up wins. I love you, Dad. I miss you tremendously. I sure hope there are beaches in heaven, because if there are, I promise I’m going to swim further out than you. Until that day when we can be beachside together again, seeya Bub.

Dad, there has never been a time when I’ve gone to the beach without thinking of you—and there never will be. You made our time at the beach together so memorable, but more than that, you taught me so many important life lessons while we were there. You taught me to slow down and relax. You taught me to soak in God’s beautiful creation. You taught me to be kind to people and get to know them, because God created them, too. You taught me to let go of all the busy things from back home and simply enjoy the life that was in front of me in that moment. I take these lessons with me everywhere I go, but especially when I go to the beach. Even though I’m still able to have fun when I go, it just isn’t the same without you. I miss our throwing sessions, and sometimes I’ll just carry a baseball in my backpack to turn over and over in my hands and think of the time we spent together. I miss trying to see who could swim the furthest out, and watching you beckon me further even when I felt like I couldn’t keep swimming. I miss walking along the shoreline with you and listening to your stories about oil rigs in the distance or planes flying overhead. You had an inquisitive, appreciative spirit for all life had to offer. And more than anything, I miss watching you enjoy those moments on the shore by yourself being the last one up. It’s strange, but sometimes it’s like I look down from the balcony and I can still see you sitting there. Dad, I know you’re still with me. I know that you’re guiding me and watching over me in everything that I do. Thank you for always being my best teacher. Thank you for being a Dad unlike any other. And thank you for always teaching me that the last one up wins. I love you, Dad. I miss you tremendously. I sure hope there are beaches in heaven, because if there are, I promise I’m going to swim further out than you. Until that day when we can be beachside together again, seeya Bub.

And my Dad was a completely selfless Father. As a child, he spent every minute he had making sure I was entertained and happy in life, even on days when he was likely tired and exhausted from work. When I was in high school, my Mom and Dad took an entire weekend to redo my bedroom to make it more appropriate for a young man in adolescence (the motif went from childhood baseball to vintage baseball—and I loved it!). If my truck broke down in high school (which was a semi-regular occurrence), my Dad was the first person there to help me. And although I’m sure there were many other exciting places he would have rather been, he was always in the stands anytime I announced a basketball or baseball game.

And my Dad was a completely selfless Father. As a child, he spent every minute he had making sure I was entertained and happy in life, even on days when he was likely tired and exhausted from work. When I was in high school, my Mom and Dad took an entire weekend to redo my bedroom to make it more appropriate for a young man in adolescence (the motif went from childhood baseball to vintage baseball—and I loved it!). If my truck broke down in high school (which was a semi-regular occurrence), my Dad was the first person there to help me. And although I’m sure there were many other exciting places he would have rather been, he was always in the stands anytime I announced a basketball or baseball game. Dad, It hurts my heart tremendously when I think that there are people out there who think your death is selfish. It pains me when I hear individuals say that death from suicide is selfish because they didn’t understand your pain. They didn’t see the despair in your eyes on that last day. They didn’t see the years that you suffered. They didn’t see how badly you wanted to be healthy. They didn’t live with the unnecessary shame that you lived with for so long. Dad, none of this makes your death and absence any easier. None of this makes the pain of losing you any less real. And yes, I wish things had gone differently on the morning of July 24, 2013—for you, for me, and for all of us. But you suffered from a disease that you didn’t understand. A disease that not even medical professionals completely understand. You died because this disease took over your brain, and I hope you know that I understand this. It doesn’t make your death right, and more than anything I wish you were still here, living the life you always lived to the fullest. But I’ve never been angry with you for your death. I’ve never loved you any less—and I never will. Dad, you are not defined by your death, but by the tremendously selfless life you led. I’m so sorry if you ever felt like you weren’t enough for us, Dad. You were always enough. You lived a completely selfless life, and I wish I was able to remind you of that. Until that day, I’ll keep fighting for your legacy. I’ll keep fighting, alongside God, to redeem the pain of losing you in an effort to try and prevent this pain in the lives of others. And until that day when I can tell you just how selfless you were, seeya Bub.

Dad, It hurts my heart tremendously when I think that there are people out there who think your death is selfish. It pains me when I hear individuals say that death from suicide is selfish because they didn’t understand your pain. They didn’t see the despair in your eyes on that last day. They didn’t see the years that you suffered. They didn’t see how badly you wanted to be healthy. They didn’t live with the unnecessary shame that you lived with for so long. Dad, none of this makes your death and absence any easier. None of this makes the pain of losing you any less real. And yes, I wish things had gone differently on the morning of July 24, 2013—for you, for me, and for all of us. But you suffered from a disease that you didn’t understand. A disease that not even medical professionals completely understand. You died because this disease took over your brain, and I hope you know that I understand this. It doesn’t make your death right, and more than anything I wish you were still here, living the life you always lived to the fullest. But I’ve never been angry with you for your death. I’ve never loved you any less—and I never will. Dad, you are not defined by your death, but by the tremendously selfless life you led. I’m so sorry if you ever felt like you weren’t enough for us, Dad. You were always enough. You lived a completely selfless life, and I wish I was able to remind you of that. Until that day, I’ll keep fighting for your legacy. I’ll keep fighting, alongside God, to redeem the pain of losing you in an effort to try and prevent this pain in the lives of others. And until that day when I can tell you just how selfless you were, seeya Bub.

Dad, I wish you could have read Reverend Walters’ book and heard his story, because I think you felt many of the things he did. I know you struggled with how to share your hurt and your pain because you didn’t want to appear weak. You didn’t want people to think you were a failure. Dad, you never failed any of us—ever. You had an illness that you couldn’t understand, and I wish we had done more to help you escape the trap that forced you into silent suffering. But Dad, I know that our Heavenly Father has welcome you into His loving arms. I know that He is redeeming your story day by day with each individual who loves you and learns from you. Dad, I will never stop loving you. I will never stop trying to find ways to help those who are hurting like you were. Keep watching over me, because I can feel it. Until I can tell you how much you are loved face-to-face, seeya Bub.

Dad, I wish you could have read Reverend Walters’ book and heard his story, because I think you felt many of the things he did. I know you struggled with how to share your hurt and your pain because you didn’t want to appear weak. You didn’t want people to think you were a failure. Dad, you never failed any of us—ever. You had an illness that you couldn’t understand, and I wish we had done more to help you escape the trap that forced you into silent suffering. But Dad, I know that our Heavenly Father has welcome you into His loving arms. I know that He is redeeming your story day by day with each individual who loves you and learns from you. Dad, I will never stop loving you. I will never stop trying to find ways to help those who are hurting like you were. Keep watching over me, because I can feel it. Until I can tell you how much you are loved face-to-face, seeya Bub.  Reverend Dan Walters

Reverend Dan Walters