“How do you tell people…how your Dad died?”

I sat across the table at a Panera from a good friend of mine. Unfortunately, we sat at that table together as victims of a similar tragedy, having each lost a parent to suicide. We talked that night about many things, especially the difficulties we encountered as grief stayed constant while life moved on.

I closed my eyes and nodded my head, because I remember asking myself this same question. I remember struggling to find the words when people asked why my Dad died so young. When I looked across that table, I saw a man walking through the same horrible questions and doubt that I had been dealing with. I would have done anything in that moment to take his pain away, because living a life after suicide makes even the most simple moments ridiculously complex. It’s hard to find the words to describe the death of a loved one when suicide enters the picture.

I thank God that, although eventually and painfully, I found the words I needed.

“My Dad committed suicide.”

“My Dad took his own life.”

“My Dad died from a suicide.”

I just didn’t know how to say it.

In the week or so after my Dad died, as crazy as this might sound, I would stand in front of my mirror at home and I would practice saying these things aloud. I would look at my own eyes, often swollen and tear-stained, and say these words to myself. Each and every time, they would break my heart.

No matter what variation I came up with, however, I just couldn’t find a way to do this. I couldn’t bring myself to say these words, mainly because they felt so unnatural. I never, never convicted my Dad of his death. I never, at any moment, held my Dad responsible for what happened to him in his battle with depression. I know that every survivor of suicide can’t say this (and that’s completely okay), but I was never at any moment mad at my Dad for what happened to him. He was not responsible for his death—depression was. Depression, a horrible and difficult to comprehend illness, stole him from his family and everything he loved. My Dad didn’t “commit” anything.

During my years in graduate school, I learned many things about life that extended far beyond the training I was receiving for a career as a college educator. One of the lessons that our faculty members constantly tried to drive home is a rather simple one: words matter. The words we choose to use each day matter. The words we use to define other people and their identities are important. It seems like a simple lesson, but I don’t think I realized just how meaningful this truth was until it hit home with my Dad’s death.

Now, in the midst of the greatest turmoil of my life, I found myself struggling each and every day to tell people how my Dad died.

I didn’t want people who didn’t know my Dad to have a wrong impression of the man he was. I didn’t want all the negative stereotypes and stigmas typically associated with suicide to discolor my Dad’s memory and legacy. If anything, I wanted people to know that even the strongest amongst our midst still suffer and still succumb. I wanted to convey this in a simple phrase—and like I do in so many areas of my life, I turned to a good book to help.

The gift of a good book is one of the most precious things you can give someone, in my opinion. I’m thankful that members of my family feel the same way. My grandmother, Pat, is an avid reader like me, and a thoughtful reader at that. Pat was my Dad’s step-mother, and in the aftermath of my Dad’s passing, Pat was extremely gracious and loving as my Mom and I continued to grieve. At the same time that she was suffering, she made sure to watch over my Mom and I, helping any way she could.

One of her most thoughtful gestures during that time came in the form of a book that has helped me in more ways than I’ll ever be able to thank her for. In an attempt to cope with her own sadness after losing my Dad, Pat came across an amazing book written by Albert Y. Hsu called Grieving a Suicide: A Loved One’s Search for Comfort, Answers & Hope. Pat was kind enough to read the book and recognize how helpful it was, and she bought two more copies: one for me, and one for my Mom. (For this book and others that helped me cope with my Dad’s death, visit the “Library” section of Seeya Bub.)

One of her most thoughtful gestures during that time came in the form of a book that has helped me in more ways than I’ll ever be able to thank her for. In an attempt to cope with her own sadness after losing my Dad, Pat came across an amazing book written by Albert Y. Hsu called Grieving a Suicide: A Loved One’s Search for Comfort, Answers & Hope. Pat was kind enough to read the book and recognize how helpful it was, and she bought two more copies: one for me, and one for my Mom. (For this book and others that helped me cope with my Dad’s death, visit the “Library” section of Seeya Bub.)

As soon as I received the book, I stopped reading what I currently had on the docket and made this my priority—and I’m so thankful that I did. This book was sent from Pat, but I know that it was also sent from God. I received the book from Grandma Pat right in the midst of my struggle to verbalize my Dad’s death. Like all good books, it came at just the right time.

In the understatement of the century, I’ll say this: Albert Hsu’s book is a real blessing and an inspiration—especially for everything I do on this blog. Hsu lost his father, Terry, to suicide. On an everyday Thursday morning, Albert received a call from his mother that is all too familiar for so many families in our country. Albert’s Mom had discovered Terry’s body, cold and lifeless, in their family home. In such a perfect way in the pages that follow, Albert describes each and every emotion that he felt and still feels and all the unique struggles he encounters as a survivor of suicide. His story is one of the most helpful things I encountered in the aftermath of my Dad’s death, for so many reasons.

And just as I was struggling with how to describe my Dad’s death, I came across a section in the book titled “How To Talk About Suicide”. It was like a message sent directly from God through another loyal follower. It was exactly, exactly what I needed in that exact moment.

Forgive the long passage, but understand how vitally important these words were for me in my struggle to grieve. Hsu wrote:

Survivors are hypersensitive to the topic of suicide. It punches us in the gut if someone jokes, “If this doesn’t work out, I’m going to kill myself!” One survivor told me that she challenges coworkers who say things like that, asking them if they’ve ever considered how painful those flip comments might be to others. Suicide is no laughing matter.

How should people describe the act of suicide? This has been an ongoing debate for some years. The traditional phrase has been to say that someone “committed suicide.” Survivors reacted against this, saying that it implies criminality, as one would commit murder. Is suicide a crime that is committed, like a burglary? In some cases, perhaps, but in many cases, no.

In the past few decades, psychologists and suicide survivor groups have moved toward saying that someone “completed suicide.” In this parlance, suicide is not a single act but the final episode in what may have been a period of self-destructive tendencies.

The problem is that in many cases, suicide is a single act, not one of a series of attempts or part of a larger pattern. Furthermore, to say that someone “completed” suicide sounds like noting a laudatory accomplishment, like completing a term paper or college degree. It also comes across as somewhat clinical and cold.

So more recently, grief organizations and counselors have suggested that we use more neutral terms: for example, someone “died of suicide” or “died by suicide.” The Compassionate Friends, an organization dedicated to helping families who have lost children, officially changed its language in 199 so that all its materials reflect this. Executive Director Diana Cunningham said, “Both expressions [‘committed suicide’ and ‘completed suicide’] perpetuate a stigma that is neither accurate nor relevant in today’s society.”

I resonate with this. I find it difficult to form the phrase “My dad committed suicide.” And it seems wholly unnatural to say that “my dad completed suicide.” It is somewhat easier to tell someone that “my dad died from suicide”… (Hsu, 2002, pp. 145-146)

I put the book down, and in that very moment I knew that I would never say the phrase “committed suicide” when describing my Dad or other people who suffered the same fate he did. I just couldn’t do it, because it didn’t accurately describe what happened to my Dad. “Committed” gave the impression that my Dad did what he did willingly and with a sound mind. That he welcomed death, even though I knew he fought against it each and every day of his life. Even though I have many questions about his death, I knew this was not the case.

I wanted to find language that reflected the fact that my Dad’s life was stolen. Stolen by a terrible disease that attacked his mind and his well-being. People don’t commit death by cancer. They don’t commit death via car accidents or strange and inexplicable illnesses. And they don’t commit suicide either. They suffer, and there’s no guilt to be felt by those who suffer from diseases that we don’t quite understand—whether physical or mental. I liked these phrases that Hsu suggested, but I still found myself searching for the perfect phrase.

And then, in the midst of all these thoughts, I heard someone say it for the first time. I don’t remember where, and I don’t even remember who said, but I heard someone refer to their loved one as a “victim of suicide.” Their loved one was a victim. A victim of a horrible illness that attacks and hijacks our thought processes to make life appear unlivable.

I knew, in that moment, that would be the phrase I used to describe my Dad’s death. I knew that that particular phrase captured the way I felt about my Dad’s death. It would send the most accurate message about my Dad’s death—that his life was cut short by a terrible disease and illness that stole his life prematurely. That I didn’t hold him responsible for that July morning in 2013. That I never, in any moment, blamed him for what happened.

So, whenever I would speak publicly about my Dad or talk to someone who asked why he died, my phrasing was always consistent and purposeful. My Dad, a strong, sturdy, and stable man was a victim. A victim of suicide. It didn’t remove the tears or the hurt, but using that phrase helped me honor my Dad each time I shared his story.

Sitting in Panera a few years after my Dad’s death, I found myself speaking passionately and purposefully to another young suicide survivor about this very topic. And I realized, in that moment, that God led me down that journey to describe my Dad’s death for a reason. I realized that words, no matter how innocuous or mundane, matter more than anything.

I admit, both selfishly and with regret, that before suicide impacted my life I never gave a second thought to how this language might bother or hurt those who were suffering. Before Dad’s death, I had a very different understanding of suicide. I would have willingly and readily used the phrase “commit suicide” without giving it a second thought.

But now, in this new life of mine, just hearing the word “suicide” causes me to stop dead in my tracks. I get goosebumps, still, every time I hear it. Because suicide has touched my life. And now, those words are personal.

To some people, this is nothing more than semantics and mental gymnastics. A meaningless attempt for someone who is hurting to cover their wounds with a bandage until the next wound surfaces. But to me, it’s everything. I believe words hold a unique power, because both the richest and poorest people in our world, separated by miles of inequality, still have stories and still have words to describe them. The psychologist Sigmund Freud said “Words have a magical power. They can bring either the greatest happiness or deepest despair; they can transfer knowledge from teacher to student; words enable the orator to sway his audience and dictate its decisions. Words are capable of arousing the strongest emotions and prompting all men’s actions.”

And I hope, with the words I choose, that I can sway someone else from meeting the same unfortunate end that my Dad found. I hope that the words I use, even those so seemingly simple as the way in which I describe his death, will cause someone to think differently about suicide, mental illness, and the need to fight against depression with everything we have.

This may sound simple, but the fight begins with the words we choose regarding suicide and mental illness. Our biggest obstacle in this battle, one that I hope you’ll join me in, is helping fight the shame and stigma of mental illness—and in order to get people to talk about how they feel, we have to make them feel that it’s okay to talk.

My words, your words, the words of hurting people—our words matter.

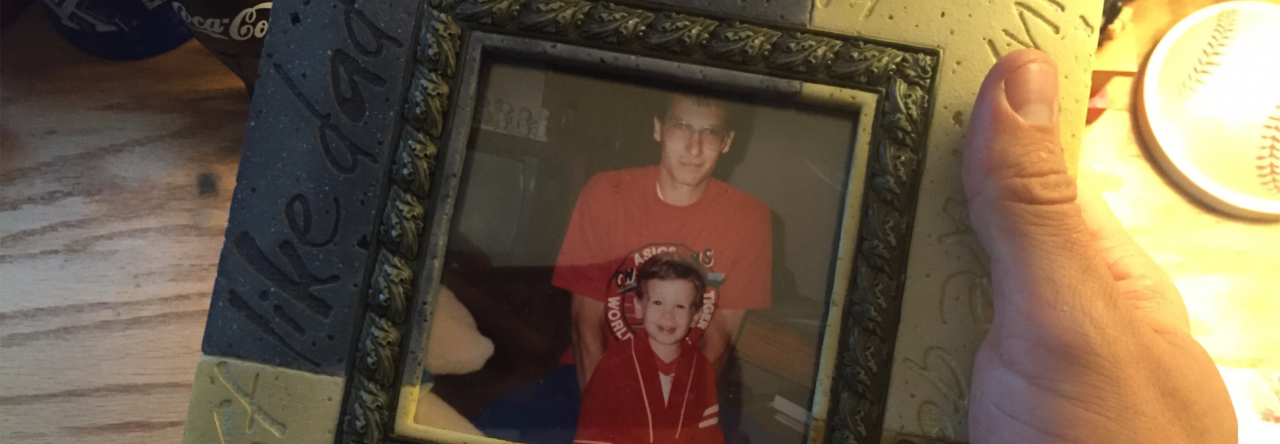

Dad, Each day I wrestle with telling your story and making sure people who never knew you know the type of man you were. I want them to know you were strong. I want them to know you were thoughtful. I want them to know you were caring and loving and everything a Father should be. I hope that the words I choose to use convey the love I have for you and the love you gave to all of us each and every day here on Earth. You never inflicted pain with the words you chose. You built people up by telling them and showing them how important they were to you. You and I had many wonderful conversations together, and we shared so many words. I’m sorry for the moments that my words may have hurt you. I wish I had spent more time telling you the words you deserved to hear—that I loved you, that I was proud of you, and that I was always there to listen when you were hurting. I know that we will have these conversations again. I wait longingly for that day. But until our words meet each other’s ears again, seeya Bub.

Dad, Each day I wrestle with telling your story and making sure people who never knew you know the type of man you were. I want them to know you were strong. I want them to know you were thoughtful. I want them to know you were caring and loving and everything a Father should be. I hope that the words I choose to use convey the love I have for you and the love you gave to all of us each and every day here on Earth. You never inflicted pain with the words you chose. You built people up by telling them and showing them how important they were to you. You and I had many wonderful conversations together, and we shared so many words. I’m sorry for the moments that my words may have hurt you. I wish I had spent more time telling you the words you deserved to hear—that I loved you, that I was proud of you, and that I was always there to listen when you were hurting. I know that we will have these conversations again. I wait longingly for that day. But until our words meet each other’s ears again, seeya Bub.

“May these words of my mouth and this meditation of my heart be pleasing in your sight, Lord, my Rock and my Redeemer.” Psalm 19:14 (NIV)

Dad, It still doesn’t seem right that this is the fourth birthday that’s passed since you left us. It doesn’t feel right that life is going on without you. There are times when my heart feels so much pain that I can’t imagine ever celebrating anything without you again. But, in a weird way, I’m thankful for this pain because it reminds me how special you made life feel while you were here. You brought a vivid color and energy to my life each and every day that I don’t know I’ll ever be able to experience until I see you again. But I will see you again. I’ll make up for all those birthdays that I wished I could do over. You and I will, one day, celebrate our new birthdays in heaven. And fortunately, we will never, ever, see those birthdays come to an end. Happy birthday, Bub. You live on in my heart each and every day. Until I can tell you this face to face once again, seeya Bub.

Dad, It still doesn’t seem right that this is the fourth birthday that’s passed since you left us. It doesn’t feel right that life is going on without you. There are times when my heart feels so much pain that I can’t imagine ever celebrating anything without you again. But, in a weird way, I’m thankful for this pain because it reminds me how special you made life feel while you were here. You brought a vivid color and energy to my life each and every day that I don’t know I’ll ever be able to experience until I see you again. But I will see you again. I’ll make up for all those birthdays that I wished I could do over. You and I will, one day, celebrate our new birthdays in heaven. And fortunately, we will never, ever, see those birthdays come to an end. Happy birthday, Bub. You live on in my heart each and every day. Until I can tell you this face to face once again, seeya Bub.

God has given me so many wonderful blessings in this life, but none greater than the two loving parents that have been with me since before I took my first breath. I’ve always had a special connection with my Mom since I was little. As an only child, I was fortunate to have all of her love and attention. I’m thankful that even though I’m growing older, I’ve never stopped receiving that.

God has given me so many wonderful blessings in this life, but none greater than the two loving parents that have been with me since before I took my first breath. I’ve always had a special connection with my Mom since I was little. As an only child, I was fortunate to have all of her love and attention. I’m thankful that even though I’m growing older, I’ve never stopped receiving that. Farm (for those of you who are old enough to remember this place), picnics, movies, making crafts, zoo trips and much more. Birthdays and holidays were also special times at the Bradshaw house. Scott and I always wanted to make Tyler’s birthdays special. Every year we would plan a big birthday party for him, and Scott was always excited and would always try to plan something different each year.

Farm (for those of you who are old enough to remember this place), picnics, movies, making crafts, zoo trips and much more. Birthdays and holidays were also special times at the Bradshaw house. Scott and I always wanted to make Tyler’s birthdays special. Every year we would plan a big birthday party for him, and Scott was always excited and would always try to plan something different each year. Dad, I always pictured you growing old with Mom. I knew you would make a tremendous Grandpa, but just as importantly I know that Mom will be an amazing Grandma someday. I hate that you didn’t get to enjoy this chapter of life here on this Earth with her. But I know that you are so unbelievably proud of her as you watch how she’s handled the troubles of this life without you. I know that you are watching over her each and every day. She is lucky to have such an amazing guardian angel. It doesn’t change the fact that we would rather have you here with us, but it does make life easier to handle knowing that, someday, we will all be reunited—a family again. Although we don’t have you here with us, we will always cherish and hold near to our hearts the memories that you gave us. You gave us so many. Thank you for always doing that. Thank you for being a wonderful Father, and thank you for choosing the best Mother any kid could ever hope for. Until we get to relive those wonderful memories together again, seeya Bub.

Dad, I always pictured you growing old with Mom. I knew you would make a tremendous Grandpa, but just as importantly I know that Mom will be an amazing Grandma someday. I hate that you didn’t get to enjoy this chapter of life here on this Earth with her. But I know that you are so unbelievably proud of her as you watch how she’s handled the troubles of this life without you. I know that you are watching over her each and every day. She is lucky to have such an amazing guardian angel. It doesn’t change the fact that we would rather have you here with us, but it does make life easier to handle knowing that, someday, we will all be reunited—a family again. Although we don’t have you here with us, we will always cherish and hold near to our hearts the memories that you gave us. You gave us so many. Thank you for always doing that. Thank you for being a wonderful Father, and thank you for choosing the best Mother any kid could ever hope for. Until we get to relive those wonderful memories together again, seeya Bub.  Becky Bradshaw

Becky Bradshaw

Dad, I wish each and every day that you were here with me still. I wish that I could hug your neck. I wish that I could ride in the truck with you. I wish, each day, that I could hear your laugh again. But more than anything, I wish I had done more to help you feel like it was okay to talk. I wish I had encouraged you, even forced you, to get the help that you deserved. In lieu of being able to tell you that now, however, I’m trying my best to use your story to save other people. I’m trying to do what you always did—help those who are down on their luck and need it most. Dad, you may not be here with me, but I hope you know that your story is making a tremendous impact. I can’t wait to just talk with you again. Until that day, seeya Bub.

Dad, I wish each and every day that you were here with me still. I wish that I could hug your neck. I wish that I could ride in the truck with you. I wish, each day, that I could hear your laugh again. But more than anything, I wish I had done more to help you feel like it was okay to talk. I wish I had encouraged you, even forced you, to get the help that you deserved. In lieu of being able to tell you that now, however, I’m trying my best to use your story to save other people. I’m trying to do what you always did—help those who are down on their luck and need it most. Dad, you may not be here with me, but I hope you know that your story is making a tremendous impact. I can’t wait to just talk with you again. Until that day, seeya Bub.