Tonight, I’ll hold a candle in my hand. A candle that represents my Father. A candle that reminds me that, although he’s gone, his memory will never, ever die out.

All the while, I’ll be surrounded by other hurting individuals, holding candles, asking the same questions as I am, experiencing the same sadness and despair that I’ve felt for the past six years.

Together, we will encourage one another. Together, we will remind one another that we are never, ever alone, no matter how isolating the world and our grief might feel.

But together, we will also serve as a powerful and uncomfortable reminder—a reminder that suicide is all-too-real, all-too-frequent, and all-to-preventable.

And together, I hope we can help open everyone’s eyes to the pain around us, just our own have been opened as well.

I never, never thought that suicide would impact my family. It wasn’t a possibility. Maybe in other people’s families; but definitely not mine.

And when it did, it opened my eyes; and they’ve been opening wider and wider ever since.

I remember the first time that it ever felt as if suicide hit close to home. A family that was very close with mine through some announcing work I had done had lost an adult brother to suicide in the middle of the baseball season. It shocked me because suicide seemed so irregular and so distant from the seemingly-perfect little world I lived in. Talking with the family at their first game back was heartbreaking. I remember leaning against the rail of the grandstand while the team was taking BP, and I didn’t quite know what to say to them; maybe because I didn’t quite know what to say about suicide in general. I likely asked questions that were nosey, pointless, and insensitive. Trying to understand their pain and anguish made me feel so unbelievably helpless. I was struggling to understand how suicide could have impacted a family that had so many wonderful people in it, but from a grander perspective, I was really struggling to understand the concept of suicide in general.

And after talking with them, heartbroken for the reality that had become their lives, I still believed that suicide was their story; not mine, and definitely not my family’s. I still believed that suicide was something so small, so random, and so seemingly disconnected from the reality that was my life that it could never, ever occur in my world—even though, by happening to them, it already had.

It wasn’t until the reality of suicide unexpectedly invaded the Bradshaw home that my eyes were truly opened wide to the reality, the prevalence, the pain, and the all-too-frequent occurrence of suicide in our country and in our own individual neighborhoods. It took a death from suicide invading my own front door for the pain to truly set in.

After the destruction of my Dad’s death and funeral had settled a bit, I found myself obsessively researching suicide and mental illness in the corner office of my small home in an effort to try to make sense of what had happened to my Dad. I knew that I’d never be able to answer most of the questions I had, because suicide at its core is an inexplicable phenomenon that doesn’t usually have a single indicator, trigger, or catalyst. In all likelihood, it’s a terrible confluence of environmental, biological, contextual, and spiritual factors that leads one to think that suicide is the only option.

Nonetheless, I looked for answers; and I found number after number, statistic after statistic, that shocked and amazed me. I had likely heard all of the numbers before, but none of them had ever carried the horribly painful weight that they now did. Now, my Dad represented one of those numbers. Now, a seemingly minor statistic had become the largest, most painful reality for my Dad and those who loved him. Those numbers surprised me, but they shouldn’t have. Those numbers shocked me, but I shouldn’t have been so numb to reality.

The reality was that these numbers had always existed and had always impacted the people in the world around me; I was just too busy, too self-focused, and too ignorant to pay any attention to them.

But everything I saw confirmed the reality. Everything I read showed me that mental illness and suicide by the numbers alone were all-too-likely to happen to those I loved. And I was ashamed to think that, for so long, I just pretended it wasn’t happening or was simply oblivious to the hurt existing in the world around me.

I was ashamed to see that, according to most every medical and research report I read, nearly one in five individuals in the United States suffers from some form of mental illness[1]. Continuing to read, I learned that there were so many people who were hurting and suffering but simply couldn’t or wouldn’t get the help they needed and deserved. Nearly 60% of adults with a mental illness didn’t receive mental health services in the past year.[2] I hated thinking that people who were hurting, like my Dad, felt ashamed of going to seek professional help.

I remember when I first learned that my Dad suffered from depression, and I recall thinking how unusual it had seemed—not just for my Dad, but for people in general. On the day I learned that my Dad couldn’t explain his despair, it felt like he was the only person in the world who was suffering and struggling. It felt as if his unexplainable sadness was something that only he dealt with. It felt as if the solution—counseling, medication, and other treatments—were so obvious.

But the life behind these numbers is much more complicated and messy. The numbers show—and now we all know—that many more people are hurting than we ever thought were. And we all know that treatment isn’t easy, often because admitting you are hurting isn’t easy.

Over those many sleepless nights after losing Dad, I kept reading and I kept researching, hoping I would be able to find a report that gave a more optimistic prognosis of the situation; but reality was much more important to me in that moment than optimism. After losing my Dad to suicide, it was more important that I had an accurate depiction of the state of affairs related to mental illness and suicide, not a pretty one. The numbers that shocked me more than the seemingly regular occurrence of mental illness, however, were those statistics related to how many individuals eventually died as a result of suicide.

I was dumbfounded to read numbers that represented real, broken, and unnecessarily-shortened lives, and those statistics related to suicide were the most heartbreaking:

- Around 123 individuals in the United States each day died from suicide.[3]

- That number translates to a death by suicide occurring every 12 minutes on average.[4]

- Suicide is the 10th leading cause of death in the United States.[5]

I still remember the horror I felt when I read these numbers after losing Dad: horror at the situation, and horror at my own ignorance to the suffering of my fellow man. It wasn’t like these deaths were occurring in a far-off world; they were occurring all around me, right in my own backyard. Mental illness shouldn’t have been a foreign concept to me.

But it was; and I was ashamed.

It wasn’t until I lost my Father that I began to see the faces and lives behind these numbers. It took the cloud of suicide rolling over my own family and my own life to realize just how bad the storm really was. It shouldn’t have had to happen that way. It shouldn’t take going through unbelievable pain and hurt to be cognizant of an epidemic that steals lives, destroys families, and creates a generational grief that is nearly impossible to escape.

My Dad saw it, too.

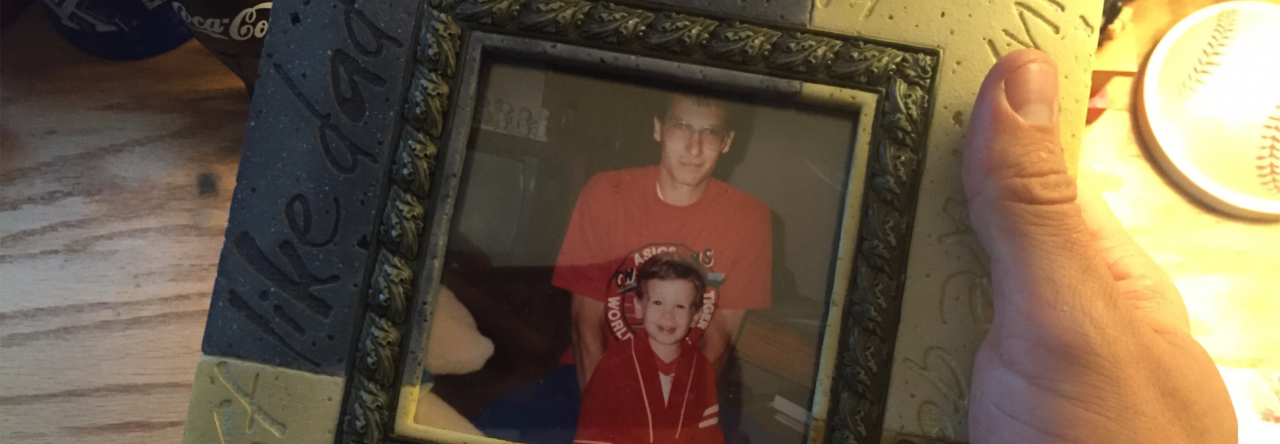

Every year at Christmas, my Mom does a wonderful job of giving me a special gift that will help me remember my Dad. These gifts are focused on his life—not his death—and they’ve always helped take off some of the painful edge that surrounds every holiday without the man who raised me. Most of the time, her gifts are something created anew out of his things and possessions, giving them fresh life and meaning for me in his absence. A few years ago, however, she gave me something completely untouched and unbelievably meaningful—she gave me my Dad’s Bible. The Bible was completely undisturbed—exactly as it had been left on the last day of his life. It was a treasure I can’t put into words.

Like me, my Dad kept a few small, flat mementos in the front of his Bible. I leafed through them, one by one, wondering why they were there and what they meant to him. Some I could explain; others I could not. As I leafed through the items, there were a number of small funeral cards and programs that Dad had saved from services that he attended. I always respected my Dad for making a point to go to funerals to support those he loved, even if it made him uncomfortable.

Amongst the three or four funeral cards inside of his Bible cover, I couldn’t help but notice the program from our family friend’s funeral—the man who had also died from suicide. My jaw hung open when I saw it and thought about the unfortunate connectedness between this poor man and my Father. Almost a year and a month from the date of our family friend’s funeral, my Dad would die from the same exact mechanism of death. My family would be scarred by the same ugly, unfortunate fate that had affected a family that meant so much to us.

My Dad saw all of this. He saw the way it influenced this other family. But even with that perspective, he couldn’t avoid the same pain being inflicted upon our own household. It shows how powerful and dangerous mental illness can become when left unchecked. It shows how suicidal ideations can ensnare and completely distort our logical thought processes. Where mental illness distorts, reality is paralyzed; and making the right decision often takes a backseat to making an emotional one.

And it shows that we can’t wait until something bad happens in our own lives to open our eyes to the hurt that exists within the hearts and minds of those we love.

Even with my eyes wide open, it’s extremely difficult to make sense of my Father dying from suicide having attended a funeral for another suicide victim just one year earlier. It’s hard to fathom how a man who loved his God, loved his family, and loved the life that he had been given could feel so sick and so full of despair that life felt unlivable.

But mental illness and depression incapacitated my Father’s ability to think about how unnecessary his death by suicide was and how it might permanently inflict, wound, and hurt those who loved him most. My Dad couldn’t turn the tide on the statistics related to suicide, even though his own personal experience in this life should have helped him do that.

But now, we are all left behind, refusing to let those numbers increase as a way to redeem my Dad’s death.

In order to really turn the tide on the horrible statistics surrounding suicide, it’s time that we open our eyes. It’s time that we start to see more than numbers, but faces and lives and stories cut short by unnecessary pain and heartache.

This evening (September 10, 2019), I plan to join a group of fellow suicide survivors (a term that describes family and friends of someone who has died from suicide) at a support and prevention event called “A Walk to Remember” at the Voice of America Park in West Chester, Ohio. I’ve been invited to say a few words to that group before we all walk together and remember our loved ones, the joy they brought to our lives, and the pain we’ve felt in losing them. After I say a few words about my Dad at the beginning of the event, I’ll join hands with those who are also hurting and struggling as we make our way through a remembrance walk, channeling positive memories of our loved ones, and wishing, more than anything, that we could have our loved ones back.

There is peace in knowing that, tonight, I’ll be surrounded by so many individuals who understand the pain that my family and I have experienced. They’ll know what it feels like to get that awful phone call. They’ll know what it feels like to have questions that will never be answered. They’ll know what it feels like to feel guilty and sad and helpless and angry all at the same time. They’ll know what it feels like to be robbed of someone you love without reason or explanation.

But as much peace as I’ll find being with that group of fellow suicide survivors tonight, there will also be something deep and troubling about the entire experience. There will be a sense of frustration in wondering how suicide can continue to impact so many lives unnecessarily. There will be a sense of anger knowing that the average number of suicides per day in the United States has actually increased since losing my Dad, not decreased. I will walk around the lake at VOA Park contemplating why our unfortunate group of suicide survivors continues to add new members in an age where the statistics are widely known.

I don’t ever want families to have to be impacted by suicide first-hand to simply become aware. We shouldn’t need to lose those we love to learn or take action, especially when it comes to deaths that are entirely preventable. I shouldn’t have had to go through what I did to become more empathetic to those who were suffering and those who were grieving. But I’m here and you’re here knowing that we must do something to make sure that suicide is stopped dead in its tracks. I’m not talking about pushing back that average time by a minute or two minutes. I’m talking about radical change. I’m talking about each and every one of us having a deep and unyielding desire to make sure that no one ever becomes a victim of suicide again. If it’s a pipe dream to want to live in a society where people don’t feel the need, desire, or unnecessary compulsion to die prematurely, I’ll live in that idealistic world each and every day.

I ask you, in this moment, wherever you are and no matter what baggage you might carry along with you every day, to make sure this dream becomes a reality; to make sure that our awareness is more than just knowing, but becomes doing.

If you are hurting and contemplating suicide, I beg you in this moment and every single moment that follows to remember that you are loved, and that you matter, and that you deserve health, love, grace, and most importantly, life. I beg you to reach out and ask for the help that you need, that you deserve, and that is available.

And if you are reading this post because you know and love someone who is hurting, I implore you to show that individual forgiveness and patience, kindness and love. I ask you to do everything you can to help those you love in any way you can. Maybe it’s a difficult but necessary conversation. Maybe it’s opening up to that person, being vulnerable, and finding comfort in your mutual pains and struggles. Maybe it’s finding the bravery to accompany that person to a therapist or counseling appointment. You can be the person that helps reverse the statistical trends.

And more than anything, I am speaking to those of you who are reading who don’t struggle or know of anyone who is struggling. The reality is that we shouldn’t have to be someone or know someone who is hurting in order to feel empathy for a broken world. Don’t embrace inaction because the battle has yet to hit your doorstep. We can all do more to make sure that suicide is an anomaly, not an every-12-minute-occurrence. And it starts with making sure all of us have eyes that are wide open to the mental illness epidemic occurring in our country.

Tonight I’ll hold a candle. I’ll hold a candle and remember my Father. I’ll hold a candle and remember all of those who died the same way he did.

But I’ll hold that candle knowing that, together, we can create a world where every man and woman walks around with eyes wide open—and more importantly, hearts that are wide open as well.

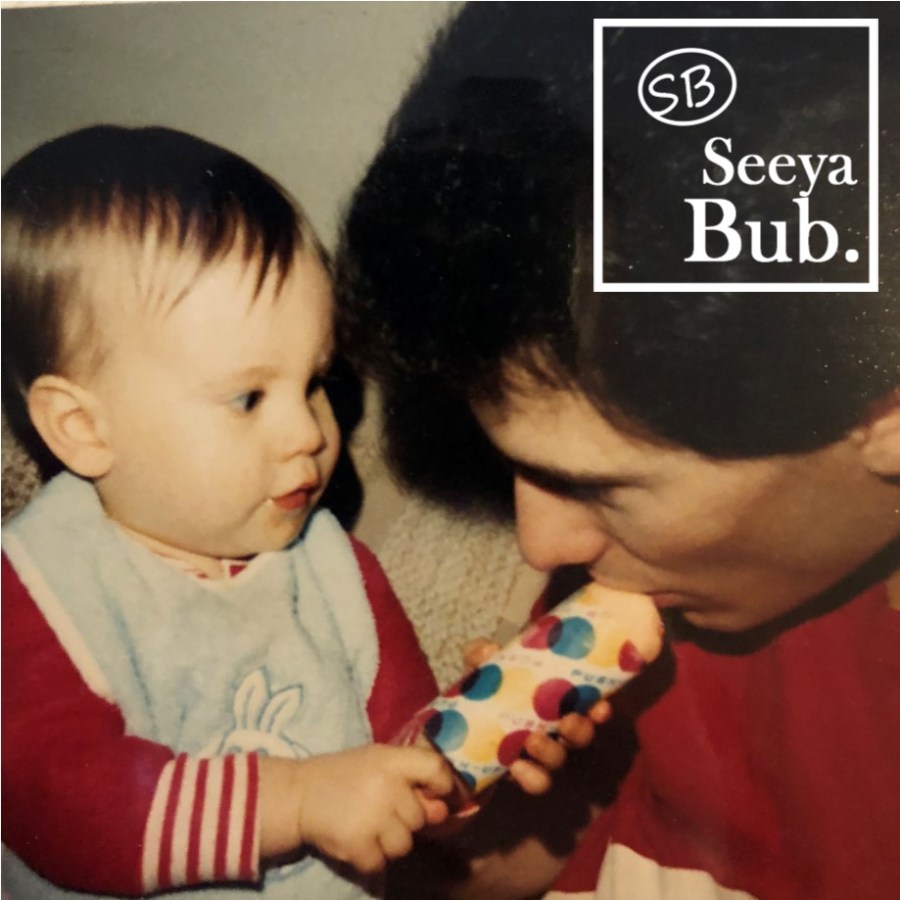

Dad, my heart breaks each day when I think about losing you, and the past six years have been unbelievably difficult. I don’t want to have to navigate life without you because you had so much more to live for. Life was simply better when you were in it, Dad. You brought joy and laughter and security to the world around you, and we’ve all felt your absence every day. I also feel tremendous guilt because I wish it wouldn’t have taken your death for me to realize just how bad you were hurting. Dad, I should have been more patient and understanding. I should have shown you more empathy and grace because you were suffering from a disease that you couldn’t explain, identify, or even put into words. There are so many moments that I wish I could redo—days in which I treated you unfairly or without compassion. Although I can’t replay and fix those moments, I want to spend every day here on Earth trying to redeem your death. I want to make sure that everyone who reads my words and hears my voice knows your story, learns from it, and chooses a different path forward because of it. Dad, you gave me the courage to carry on in the face of your death, and although I’d do just about anything to have you back, I’m so grateful that you taught me to do everything I can to help others who are hurting. Thank you for always loving me. Thank you for always teaching me, even in your death. Thank you for all you gave to me, even on days when you couldn’t even take care of yourself. I love you, Dad, and I miss you tremendously. I can’t wait to be reunited forever in the glory of God’s eternal kingdom. Until that day, seeya Bub.

Dad, my heart breaks each day when I think about losing you, and the past six years have been unbelievably difficult. I don’t want to have to navigate life without you because you had so much more to live for. Life was simply better when you were in it, Dad. You brought joy and laughter and security to the world around you, and we’ve all felt your absence every day. I also feel tremendous guilt because I wish it wouldn’t have taken your death for me to realize just how bad you were hurting. Dad, I should have been more patient and understanding. I should have shown you more empathy and grace because you were suffering from a disease that you couldn’t explain, identify, or even put into words. There are so many moments that I wish I could redo—days in which I treated you unfairly or without compassion. Although I can’t replay and fix those moments, I want to spend every day here on Earth trying to redeem your death. I want to make sure that everyone who reads my words and hears my voice knows your story, learns from it, and chooses a different path forward because of it. Dad, you gave me the courage to carry on in the face of your death, and although I’d do just about anything to have you back, I’m so grateful that you taught me to do everything I can to help others who are hurting. Thank you for always loving me. Thank you for always teaching me, even in your death. Thank you for all you gave to me, even on days when you couldn’t even take care of yourself. I love you, Dad, and I miss you tremendously. I can’t wait to be reunited forever in the glory of God’s eternal kingdom. Until that day, seeya Bub.

“Rejoice with those who rejoice, weep with those who weep.” Romans 12:15 (ESV)

*Authors Note: For clarity and accuracy in writing, please note that all statistics have been updated to reflect recent research that is published at the time of writing/publication of this post (Fall 2019). Unfortunately, many statistics related to the prevalence of mental illness and suicide have continued to grow since my Father’s death in 2013.

References:

[1] https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/statistics/mental-illness.shtml#part_154785

[2] https://www.nami.org/NAMI/media/NAMI-Media/Infographics/GeneralMHFacts.pdf

[3] https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/suicide/fastfact.html

[4] https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/suicide/fastfact.html

[5] https://www.nami.org/NAMI/media/NAMI-Media/Infographics/GeneralMHFacts.pdf

In

In  The books and bobbleheads had been removed months earlier, but the chair molding and paint were still on the walls, and I couldn’t help but run my hands across the work Dad had done and feel like I was right there next to him again. His work put breath to his memory even though he had taken his final breath many years ago. He treated that job, like every job he had, with an obsessive attention to detail, making sure the chair molding ran into the closet, ended at a perfect angle, and didn’t impede the closet door’s ability to close. It was exactly what I wanted.

The books and bobbleheads had been removed months earlier, but the chair molding and paint were still on the walls, and I couldn’t help but run my hands across the work Dad had done and feel like I was right there next to him again. His work put breath to his memory even though he had taken his final breath many years ago. He treated that job, like every job he had, with an obsessive attention to detail, making sure the chair molding ran into the closet, ended at a perfect angle, and didn’t impede the closet door’s ability to close. It was exactly what I wanted. Dad, Leaving my house on Gateway Drive for the last time felt like I was leaving another piece of you behind. It’s so easy for me to associate you with that house because you were so instrumental in making my first home a reality. You were there, step by step, as I faced the challenges of becoming a new homeowner, and you helped me face those head-on….or shell-on in the case of that vicious snapping turtle in the pond! I have so many positive memories of the year that we lived right next door to one another. I miss you showing up at the backdoor and hanging out just because you wanted to say hello. There were moments in that home after losing you that were so difficult—but they were also so important. They were moments where I could picture you and see you and hear your voice again, and as the years wear on, part of me worries that I’ll lose some of those memories. But Dad, you’re always with me—whether I own that home or not. You’re always walking right alongside of me guiding and directing me, and I’ll never, ever forget that. I’m glad for that year we spent as neighbors, but I’m even more grateful for the 26 years we spent as Father and Son. Dad, I’ll never quit loving you. I’ll never quit wishing you were still here with us, and that the pain you felt on this Earth had never existed. But I’ll also never stop thinking about the moment that you and I will be reunited again in Heaven. We will be neighbors in an Eternal Kingdom, and I’ll look forward to more-than-a-lifetime of laughter and love again. But until that day, seeya Bub.

Dad, Leaving my house on Gateway Drive for the last time felt like I was leaving another piece of you behind. It’s so easy for me to associate you with that house because you were so instrumental in making my first home a reality. You were there, step by step, as I faced the challenges of becoming a new homeowner, and you helped me face those head-on….or shell-on in the case of that vicious snapping turtle in the pond! I have so many positive memories of the year that we lived right next door to one another. I miss you showing up at the backdoor and hanging out just because you wanted to say hello. There were moments in that home after losing you that were so difficult—but they were also so important. They were moments where I could picture you and see you and hear your voice again, and as the years wear on, part of me worries that I’ll lose some of those memories. But Dad, you’re always with me—whether I own that home or not. You’re always walking right alongside of me guiding and directing me, and I’ll never, ever forget that. I’m glad for that year we spent as neighbors, but I’m even more grateful for the 26 years we spent as Father and Son. Dad, I’ll never quit loving you. I’ll never quit wishing you were still here with us, and that the pain you felt on this Earth had never existed. But I’ll also never stop thinking about the moment that you and I will be reunited again in Heaven. We will be neighbors in an Eternal Kingdom, and I’ll look forward to more-than-a-lifetime of laughter and love again. But until that day, seeya Bub.

Dad, You lived a big and vibrant life while you were here with all of us, and your absence is even more noticeable and painful because the void left behind is so great. You deserved to live a fuller life than the one you experienced, and I’m sorry I didn’t do more to make that dream reality. Dad, I would have loved watching you grow old—even though it might not have been as much fun for you as it would have been for me. I would have loved seeing you on my wedding day, and you have no idea how much I would have appreciated your wisdom about navigating this new chapter in my life because you were such an amazing husband for Mom. And yes, I would have loved watching you become a grandpa more than anything else. I know you would have been silly and goofy and ridiculous—and completely adored by your grandchildren. But Dad, as much as I wanted to watch those things for myself, I’m ultimately saddened because you earned the right to experience all of those wonderful things. I hate mental illness and suicide for robbing you of these life chapters. Mental illness separated you from us and from many wonderful, beautiful moments that awaited your future. And although I won’t get to watch you enjoy life, and although I’ll always have questions about why this happened to you, I do find peace knowing that you’re not suffering any longer. I find a sense of comfort knowing that the unjustified feelings of shame and embarrassment that you experienced in this world are completely gone and fully redeemed. And I know that as great as any experience you could have had here with us might have been, you’re experiencing a joy and beauty beyond any other as you bask in the glory of Heaven and God’s everlasting love and paradise. Dad, keep watching over me, and keep reassuring me that you were called Home for a reason. I love you, and I wish we could have experienced more of this life together; but I know there’s a greater reward and an unbelievable reunion awaiting us. Thank you Dad, and until the day when we are reunited forever, seeya Bub.

Dad, You lived a big and vibrant life while you were here with all of us, and your absence is even more noticeable and painful because the void left behind is so great. You deserved to live a fuller life than the one you experienced, and I’m sorry I didn’t do more to make that dream reality. Dad, I would have loved watching you grow old—even though it might not have been as much fun for you as it would have been for me. I would have loved seeing you on my wedding day, and you have no idea how much I would have appreciated your wisdom about navigating this new chapter in my life because you were such an amazing husband for Mom. And yes, I would have loved watching you become a grandpa more than anything else. I know you would have been silly and goofy and ridiculous—and completely adored by your grandchildren. But Dad, as much as I wanted to watch those things for myself, I’m ultimately saddened because you earned the right to experience all of those wonderful things. I hate mental illness and suicide for robbing you of these life chapters. Mental illness separated you from us and from many wonderful, beautiful moments that awaited your future. And although I won’t get to watch you enjoy life, and although I’ll always have questions about why this happened to you, I do find peace knowing that you’re not suffering any longer. I find a sense of comfort knowing that the unjustified feelings of shame and embarrassment that you experienced in this world are completely gone and fully redeemed. And I know that as great as any experience you could have had here with us might have been, you’re experiencing a joy and beauty beyond any other as you bask in the glory of Heaven and God’s everlasting love and paradise. Dad, keep watching over me, and keep reassuring me that you were called Home for a reason. I love you, and I wish we could have experienced more of this life together; but I know there’s a greater reward and an unbelievable reunion awaiting us. Thank you Dad, and until the day when we are reunited forever, seeya Bub.

Dad, I’m sorry for all of those moments that we should have spent together. I’m sorry for all of those times that I wasted when we had the opportunity to just be together, but I didn’t realize the value of those moments. Ultimately, I’m just sorry we didn’t have more time. Dad, you brought such joy to my life—and to everyone’s life that you interacted with. Any amount of time with you would have failed to be enough. There are so many things we should have done together, and I’m sorry I didn’t make a more genuine effort to make those things happen. Dad, I hope that I’m still learning from your life. I hope that I am taking the time that God has given me and using it more wisely than I did before you died. It still doesn’t erase the pain of losing you and the desire to have more of you in my life, but I hope that I’m realizing the fragility of life and the need to invest my time in the things that matter—the things associated with loving God and loving other people. Dad, please continue teaching me. Thank you for living a vivid life that still feels important each and every day. And Dad, I’m keeping a list of all those things we should have done. Someday, we will have the opportunity to do them all, and I can’t wait. Until that day and the glorious reunion that awaits, seeya Bub.

Dad, I’m sorry for all of those moments that we should have spent together. I’m sorry for all of those times that I wasted when we had the opportunity to just be together, but I didn’t realize the value of those moments. Ultimately, I’m just sorry we didn’t have more time. Dad, you brought such joy to my life—and to everyone’s life that you interacted with. Any amount of time with you would have failed to be enough. There are so many things we should have done together, and I’m sorry I didn’t make a more genuine effort to make those things happen. Dad, I hope that I’m still learning from your life. I hope that I am taking the time that God has given me and using it more wisely than I did before you died. It still doesn’t erase the pain of losing you and the desire to have more of you in my life, but I hope that I’m realizing the fragility of life and the need to invest my time in the things that matter—the things associated with loving God and loving other people. Dad, please continue teaching me. Thank you for living a vivid life that still feels important each and every day. And Dad, I’m keeping a list of all those things we should have done. Someday, we will have the opportunity to do them all, and I can’t wait. Until that day and the glorious reunion that awaits, seeya Bub.

Like Sherlock Holmes getting ready to divulge the certain facts of a case that only he could divulge, Dad took a deep breath with a smug look on his face and launched into his explanation. “Because socks wear differently. Over time, the heels and toes start to get worn thin, and you can’t be comfortable in one thick sock that’s brand new and one thin sock that’s about to get a hole. So, I number them, and I don’t have to worry about that problem any longer.”

Like Sherlock Holmes getting ready to divulge the certain facts of a case that only he could divulge, Dad took a deep breath with a smug look on his face and launched into his explanation. “Because socks wear differently. Over time, the heels and toes start to get worn thin, and you can’t be comfortable in one thick sock that’s brand new and one thin sock that’s about to get a hole. So, I number them, and I don’t have to worry about that problem any longer.” Dad, I still laugh when I think about your sock-numbering-insanity. I still smile when I think about all of the times I would rib you about putting numbers and letters on all your socks, and I can’t believe I’m saying this, but I really miss seeing those numbers. More importantly, I miss seeing you kick your feet up on the recliner in our family room. I miss laughing with you while we watched television together. I miss hearing you snore as you napped in the recliner wearing your lucky pair of 14’s, and I miss those moments of levity and peace that we were able to build in our family home. Your personality was a force for good in our family, Dad. Through the big moments and the little, everyday behaviors, you made our home a better place. You made all of us better people—even though you couldn’t get anyone to join in on your sock-numbering. Those beautiful little moments gave life vivid color. You gave us entertainment and joy in seemingly simple ways, and I’m glad that I remember the quirks of your personality. I’m glad that I can focus on the simplistic beauty of your life without obsessing over its tragic end. Dad, thank you for always making life more beautiful. Thank you for giving to all of us more than we could have ever given you in return. I miss you tremendously. I miss you each and every day. And if I get to Heaven and you have numbered socks on, I seriously don’t know what I’m going to say to you. I’m sure you’ll keep me on my non-numbered toes. But until I can tease you again, seeya Bub.

Dad, I still laugh when I think about your sock-numbering-insanity. I still smile when I think about all of the times I would rib you about putting numbers and letters on all your socks, and I can’t believe I’m saying this, but I really miss seeing those numbers. More importantly, I miss seeing you kick your feet up on the recliner in our family room. I miss laughing with you while we watched television together. I miss hearing you snore as you napped in the recliner wearing your lucky pair of 14’s, and I miss those moments of levity and peace that we were able to build in our family home. Your personality was a force for good in our family, Dad. Through the big moments and the little, everyday behaviors, you made our home a better place. You made all of us better people—even though you couldn’t get anyone to join in on your sock-numbering. Those beautiful little moments gave life vivid color. You gave us entertainment and joy in seemingly simple ways, and I’m glad that I remember the quirks of your personality. I’m glad that I can focus on the simplistic beauty of your life without obsessing over its tragic end. Dad, thank you for always making life more beautiful. Thank you for giving to all of us more than we could have ever given you in return. I miss you tremendously. I miss you each and every day. And if I get to Heaven and you have numbered socks on, I seriously don’t know what I’m going to say to you. I’m sure you’ll keep me on my non-numbered toes. But until I can tease you again, seeya Bub.

Every single day is difficult—all 1,827 of them; but every single year, July 24 is a date that stares at me from the calendar. It looms in the distance for months, and when it passes, I always breathe a sigh of relief that it’s come and gone. But I know, deep down, that it’s coming again. It will always be there. No particular July 24 has been more or less difficult—just different. But because of the nice, round number, this one feels like a milestone. A milestone I wish I didn’t have to reach.

Every single day is difficult—all 1,827 of them; but every single year, July 24 is a date that stares at me from the calendar. It looms in the distance for months, and when it passes, I always breathe a sigh of relief that it’s come and gone. But I know, deep down, that it’s coming again. It will always be there. No particular July 24 has been more or less difficult—just different. But because of the nice, round number, this one feels like a milestone. A milestone I wish I didn’t have to reach. But guess what? No amount of procrastination could stop that date from coming. No amount of denial could stop me from thinking about what this day represents. This day would come—and yes, it would eventually pass—but the second it did, the clock just begin counting down towards another unfortunate milestone. The next Christmas. The next birthday. The next Father’s Day.

But guess what? No amount of procrastination could stop that date from coming. No amount of denial could stop me from thinking about what this day represents. This day would come—and yes, it would eventually pass—but the second it did, the clock just begin counting down towards another unfortunate milestone. The next Christmas. The next birthday. The next Father’s Day. On the other side of all that grief and sadness, there will be an everlasting love made whole again. On the other side of that grief, there will be a man whom I recognize, smiling and welcoming me into his arms. In that moment, I’ll love never having to say “seeya, Bub” again. That day is coming, although it’s very far off.

On the other side of all that grief and sadness, there will be an everlasting love made whole again. On the other side of that grief, there will be a man whom I recognize, smiling and welcoming me into his arms. In that moment, I’ll love never having to say “seeya, Bub” again. That day is coming, although it’s very far off. Dad, I cry so much when I think that it’s been five years since you and I last talked. Sometimes, those tears are unstoppable. We never even went five days in this life without talking to one another. Dad, it really has felt like an eternity—but sometimes your memory is so real and so vivid that it seems like it was just yesterday when we lost you. But I know the real time. I know that it’s been five whole years since we’ve been able to be in your presence. And life simply isn’t the same without you. We all cling to your memory. We marvel at the things you built and the way you provided for our family. We laugh about the funny things you did to make life more fun. But I also weep when I think about how much life you had left to live. Dad, I’m so sorry that you were sick. I feel horrible that we couldn’t do more to help you find the cure you deserved. I’m sorry that you were robbed of the life you deserved to enjoy. I’ve felt so much guilt in losing you Dad. I know that you don’t want me to feel this way, but I just wish there was more I could have done. You deserved that, Dad. You deserved more, because you gave everything. As painful as these five years have been, Dad, I find peace in the truth of Eternity. I find comfort knowing that you are enjoying God’s eternal glory in a paradise that I can’t even begin to fathom. Dad, thank you for watching over me for these past five years. Thank you for never giving up on me—both in this life, and in the next. Thank you for giving me a lifetime of memories and an example of what fatherhood should be. I love you, Dad. I always did, and I always will. Thank you for loving me back. Until I see you again, seeya Bub.

Dad, I cry so much when I think that it’s been five years since you and I last talked. Sometimes, those tears are unstoppable. We never even went five days in this life without talking to one another. Dad, it really has felt like an eternity—but sometimes your memory is so real and so vivid that it seems like it was just yesterday when we lost you. But I know the real time. I know that it’s been five whole years since we’ve been able to be in your presence. And life simply isn’t the same without you. We all cling to your memory. We marvel at the things you built and the way you provided for our family. We laugh about the funny things you did to make life more fun. But I also weep when I think about how much life you had left to live. Dad, I’m so sorry that you were sick. I feel horrible that we couldn’t do more to help you find the cure you deserved. I’m sorry that you were robbed of the life you deserved to enjoy. I’ve felt so much guilt in losing you Dad. I know that you don’t want me to feel this way, but I just wish there was more I could have done. You deserved that, Dad. You deserved more, because you gave everything. As painful as these five years have been, Dad, I find peace in the truth of Eternity. I find comfort knowing that you are enjoying God’s eternal glory in a paradise that I can’t even begin to fathom. Dad, thank you for watching over me for these past five years. Thank you for never giving up on me—both in this life, and in the next. Thank you for giving me a lifetime of memories and an example of what fatherhood should be. I love you, Dad. I always did, and I always will. Thank you for loving me back. Until I see you again, seeya Bub.

Dad, I don’t know if I could ever relate how much you loved ice cream and how often you enjoyed eating it. I have so many wonderful memories of getting ice cream with you and Mom on those hot summer evenings as a kid growing up. You always gave our family so much to enjoy, and we’ve felt that absence in our heart ever since you left. I miss watching you find a huge chocolate chunk in your black raspberry chip and the exaggerated excitement as you compared it to the size of my head (which was either a testament to the chocolate or insult to my head size). I miss finding empty pints and spoons in the family room next to your chair. I miss those random moments when life would get me down and you would propose the solution of riding out to get an ice cream to make it all better—I wish I had taken you up on it more than I did. Dad, through ice cream and everything you ever did, you taught me to enjoy the beauty of life and all its offerings. I know that I often take life too seriously. I often get so busy and so distracted that I forget to appreciate every bite and every minute that this life has to offer. It always hits me hard when I think of your memory, and I realize in those moments how much I want to be like you. Thank you for giving me these reminders. It’s these little moments in the absence of your being here with us that have provided the most solace and refuge for my soul. Thanks for being a Dad full of love; for ice cream, yes, but mostly for your family. I have no doubt there’s Graeter’s in heaven, and I’m sure you’re still their best customer. Until we can enjoy a few more pints together, I’ll keep missing you here. But I’ll never, ever forget you. I love you, Dad. Seeya, bub.

Dad, I don’t know if I could ever relate how much you loved ice cream and how often you enjoyed eating it. I have so many wonderful memories of getting ice cream with you and Mom on those hot summer evenings as a kid growing up. You always gave our family so much to enjoy, and we’ve felt that absence in our heart ever since you left. I miss watching you find a huge chocolate chunk in your black raspberry chip and the exaggerated excitement as you compared it to the size of my head (which was either a testament to the chocolate or insult to my head size). I miss finding empty pints and spoons in the family room next to your chair. I miss those random moments when life would get me down and you would propose the solution of riding out to get an ice cream to make it all better—I wish I had taken you up on it more than I did. Dad, through ice cream and everything you ever did, you taught me to enjoy the beauty of life and all its offerings. I know that I often take life too seriously. I often get so busy and so distracted that I forget to appreciate every bite and every minute that this life has to offer. It always hits me hard when I think of your memory, and I realize in those moments how much I want to be like you. Thank you for giving me these reminders. It’s these little moments in the absence of your being here with us that have provided the most solace and refuge for my soul. Thanks for being a Dad full of love; for ice cream, yes, but mostly for your family. I have no doubt there’s Graeter’s in heaven, and I’m sure you’re still their best customer. Until we can enjoy a few more pints together, I’ll keep missing you here. But I’ll never, ever forget you. I love you, Dad. Seeya, bub.

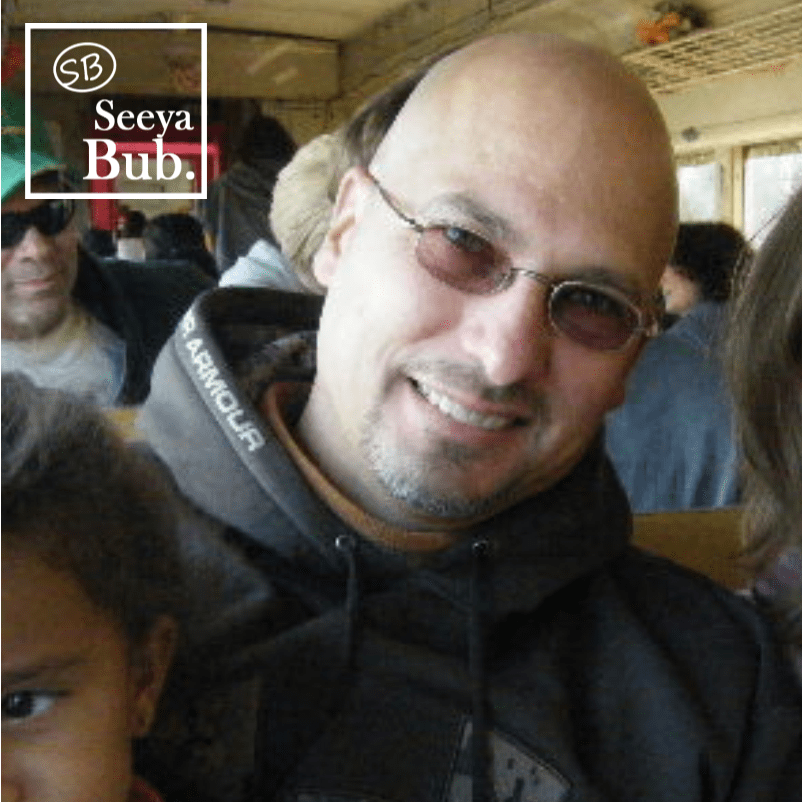

Dad, There were so many moments just like that night in college where your presence alone was all I needed to find happiness. You had an uncanny way of knowing the moments when people needed you most, and you responded with grace and unconditional love each time you were called. Nearly every day, Dad, I experience a moment when I just wish more than anything that you were here. I miss your smile, your voice, your heart, your shiny bald head, and everything that made you so very special. But in those moments where I experience your loss most severely, I try and remind myself that you are here. You are still watching. You are still listening. And you are still loving me and all those who feel your absence. Dad, thank you for always being there and for still being here. Thank you for being at my side at a moment’s notice–both in the moments when I knew I needed you, and especially in those I didn’t. I’ll never be able to say thank you enough. But, until that day when I try my best to let you know how much you are missed and how much you are loved, seeya Bub.

Dad, There were so many moments just like that night in college where your presence alone was all I needed to find happiness. You had an uncanny way of knowing the moments when people needed you most, and you responded with grace and unconditional love each time you were called. Nearly every day, Dad, I experience a moment when I just wish more than anything that you were here. I miss your smile, your voice, your heart, your shiny bald head, and everything that made you so very special. But in those moments where I experience your loss most severely, I try and remind myself that you are here. You are still watching. You are still listening. And you are still loving me and all those who feel your absence. Dad, thank you for always being there and for still being here. Thank you for being at my side at a moment’s notice–both in the moments when I knew I needed you, and especially in those I didn’t. I’ll never be able to say thank you enough. But, until that day when I try my best to let you know how much you are missed and how much you are loved, seeya Bub.

Dad, I can still go back to that specific Sunday morning and remember the quizzical look on your face when we were handed that baggie with a grape and a raisin. I can remember and picture the way you engaged in that illustration. I can remember you always reminding me many Sundays after that about how I needed to live with a grape heart. But more than all of those memories, I remember the way you lived. I remember the way you loved others. I remember the way you lived and loved with a grape heart every single day. I’m trying to live more like you because you always showed people that your love was more than a sentiment. It meant something and it made a difference. It’s hard to find people who love others the way you did—and the way you still do from above. I still feel your love each and every day. I still feel your love guiding me through all the good times and the difficult times, and I’m thankful that your grape heart lives on. I wish I could tell you this in person. I wish I could give you the praise that you deserved. Until I can see you again and give you a big hug, seeya Bub.

Dad, I can still go back to that specific Sunday morning and remember the quizzical look on your face when we were handed that baggie with a grape and a raisin. I can remember and picture the way you engaged in that illustration. I can remember you always reminding me many Sundays after that about how I needed to live with a grape heart. But more than all of those memories, I remember the way you lived. I remember the way you loved others. I remember the way you lived and loved with a grape heart every single day. I’m trying to live more like you because you always showed people that your love was more than a sentiment. It meant something and it made a difference. It’s hard to find people who love others the way you did—and the way you still do from above. I still feel your love each and every day. I still feel your love guiding me through all the good times and the difficult times, and I’m thankful that your grape heart lives on. I wish I could tell you this in person. I wish I could give you the praise that you deserved. Until I can see you again and give you a big hug, seeya Bub.

Positive, upbeat, and always smiling, my Aunt Vivian was more like a grandmother to me when I was younger. Both of my parents worked (and worked hard) to provide for our family, which meant I was often in the care of family members like my grandparents. And of course, Auntie was always in that rotation—and I couldn’t have been more thankful. Early on in my life, and during the summer months as I aged, I spent many a day under the loving and watchful eye of my Auntie. I’m a better man today because of all those days I spent with her growing up.

Positive, upbeat, and always smiling, my Aunt Vivian was more like a grandmother to me when I was younger. Both of my parents worked (and worked hard) to provide for our family, which meant I was often in the care of family members like my grandparents. And of course, Auntie was always in that rotation—and I couldn’t have been more thankful. Early on in my life, and during the summer months as I aged, I spent many a day under the loving and watchful eye of my Auntie. I’m a better man today because of all those days I spent with her growing up.

I have a few prized and cherished treasures in my possession. They aren’t the things I’ve spent the most money on. They aren’t the name-branded and logoed sweaters I can’t afford but buy anyway. They aren’t the pieces of sports memorabilia I have accumulated. They are things that are truly irreplaceable. One of a kind. Sacred.

I have a few prized and cherished treasures in my possession. They aren’t the things I’ve spent the most money on. They aren’t the name-branded and logoed sweaters I can’t afford but buy anyway. They aren’t the pieces of sports memorabilia I have accumulated. They are things that are truly irreplaceable. One of a kind. Sacred. Eventually, I got out of bed. Although there have been other days when I can’t. And during every one of those moments, I remind myself. Fear is knocking at the door. Faith must answer. My faith has led me through the challenge of my Dad’s death on days when I just couldn’t do it. It breaks my heart to watch families impacted by suicide or traumatic loss who turn away from their faith, because I know that my faith and the love of Jesus Christ has been the most important component of my survival in life after Dad.

Eventually, I got out of bed. Although there have been other days when I can’t. And during every one of those moments, I remind myself. Fear is knocking at the door. Faith must answer. My faith has led me through the challenge of my Dad’s death on days when I just couldn’t do it. It breaks my heart to watch families impacted by suicide or traumatic loss who turn away from their faith, because I know that my faith and the love of Jesus Christ has been the most important component of my survival in life after Dad. Dad, There have been so many days after your death that have been full of fear. I didn’t know what I would ever do without you, because you were such a rock for our family. While you were here with us on Earth, however, you gave us all a great example of what faith and courage looked like. Dad, you fought so hard for so long. I can’t imagine how many painful days you must have had and how many times you pushed through when life seemed unbearable. I wish that I could have done more to help you. I’m thankful that we’ve had wonderful family, like Auntie, to help us in your absence. But I know you’re still watching over us. All of us, each and every day. I love you, Dad. I continue to be afraid of what life will be like without you in the years and decades to come, but I know I’ll see you again. Until that day, seeya Bub.

Dad, There have been so many days after your death that have been full of fear. I didn’t know what I would ever do without you, because you were such a rock for our family. While you were here with us on Earth, however, you gave us all a great example of what faith and courage looked like. Dad, you fought so hard for so long. I can’t imagine how many painful days you must have had and how many times you pushed through when life seemed unbearable. I wish that I could have done more to help you. I’m thankful that we’ve had wonderful family, like Auntie, to help us in your absence. But I know you’re still watching over us. All of us, each and every day. I love you, Dad. I continue to be afraid of what life will be like without you in the years and decades to come, but I know I’ll see you again. Until that day, seeya Bub.