Note: This is the concluding piece in a series on mental illness and the Christian church. Before reading, please read the introductory message on the silence of the church (Part 1), and the previous post on the stigmas that cause this silence (Part 2).

Silence pervades our pews.

Silence pervades our pulpits.

Silence causes Christians to continue hurting unnecessarily.

And we should do something about it.

Yet, the church largely recoils when they have a chance to address the stigmas that cause this silence.

A head on attack is needed. It’s time for Christians to put on the armor of God and face this enemy down once and for all.

We can talk about the silence, and we can talk about the stigmas. But we have to talk about the solutions to make any real and lasting change.

I’ve said this a few times in this short series, but I feel the need to say it again. I’m not a trained minister. I didn’t go to college for theology or ministerial education. I’ve never led a church from the corner office or the pulpit.

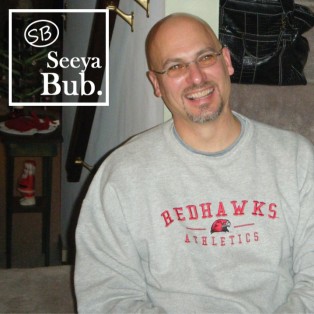

But I have sat in the pews brokenhearted. I have watched people in the church, like my Dad, feel like their struggles with mental illness and depression are still unspeakable. I’ve felt the deep wounds of suicide and the loss of a loved one that results.

And I want to do something about it.

So, I set out to write this series knowing that I would end right here. I knew that I would end my writing about the church and mental illness from a vantage point of productivity and action. I knew that solutions would be the end game.

To some, these solutions might seem obvious, and others may find their churches are already doing these things (which I hope is the case). But for me and my vantage point on the larger Christian church in America, I think enacting these five solutions would help the church became the leader in the fight against mental illness.

Solution 1: Pastors and ministers must find the courage to speak from the pulpit about mental illness. Pastors and clergymen: You’ve been called by God to lead your flock—the entire flock. And that includes members of your flock who suffer from mental illness.

God has given you a tremendous responsibility, and I don’t envy the job he’s entrusted to you. You have a difficult mission on this Earth, no doubt. There is unbelievable responsibility heaped upon your shoulders. But you’ve been selected for this job by God for a reason, and you are more equipped than you think to lead your congregations on this issue.

As I mentioned in earlier posts, research has shown that most pastors who avoid preaching on the topic of mental illness do so because they feel unprepared and unequipped to talk intelligently about the topic. This can no longer be an excuse. Pastors and church representatives should take the responsibility to be active learners and to seek out the information they currently lack. I’m not saying that all pastors should have to earn a doctorate in psychology, but I am saying that they should find ways, both formal and informal, to familiarize themselves with the topic. Maybe it’s a book. Maybe it’s a YouTube series. Maybe it’s coffee and a conversation with a local mental health professional in your community. No matter the method, it’s time for pastors to buckle down and understand the ins and outs of depression, anxiety, suicide, and all the other mental illnesses that our fellow believers suffer from.

If 20% of your congregation suddenly lost a family member to cancer, I’m sure you would do whatever it took to learn more about the disease and how to cope with sudden and instantaneous grief. If 20% of your congregation had to file personal bankruptcy, I’m sure you would take this as a cue to learn more about God’s plan for our finances. You might even preach an entire series on God’s perspective of wealth, money, and tithing.

So why do we not treat mental illness with this same level of interest and seriousness?

Studies have shown us that it is very likely that at least 20% of your congregation is suffering from some form of mental illness. So, it’s time for you to be a student again. It’s time for you to equip yourself with knowledge. We can’t just hide behind the excuse that we aren’t equipped to talk about the subject as a cop out. We live in the greatest information age of all time. Yes, we may have to work and be studious to understand it, but I believe God has called you to do that.

Solution 2: Churches should provide education campaigns to their entire congregation (not just those who are suffering) to help counter the dangerous stigmas that exist. Learning and listening cannot be the sole responsibility of church leaders if we expect to win this fight. Churches and congregations across the country must offer and engage in active, intentional educational campaigns to fight back the dangerous stigmas that prevent us from serving the mentally ill. The church should play a more active role in offering education and awareness programs intentionally designed to defeat these faulty beliefs once and for all.

Each church might deliver this differently, which is the beauty of the community God has created. In the 12th chapter of Romans, Paul beautifully articulates the brilliance of the Christian church, saying that each member (and in effect each church) serves a different purpose in the larger family of Christ. All churches are connected by a common belief system, and there can be no division between us on our foundational beliefs, but God brings together a diverse group of believers for a reason. As a result, their translation of God’s values into particular actions and programs might vary from group to group, as long as they are grounded in the mission and love of Jesus Christ.

Church leaders should pray seriously about how their flock might best engage with the topic of mental illness. For some churches, it might be a sermon series on mental illness. For others, it might be a small group discussion or a Bible/book study. It could be a guest sermon from a Christian counselor who serves those who are suffering. And for others yet, some believers might learn best by actually engaging with the mentally ill at a local treatment facility. No matter the delivery method, Christian believers of all functions within the church, from those at the most powerful positions to the individuals who just worship every Sunday, must fight ignorance with knowledge and information. Walk a mile in their shoes. Work to understand what you don’t understand. Jesus came down to walk among us, and we should also walk amongst those who are hurting.

Let me add an important note: If you are offering these programs solely to those who are suffering, you really are preaching to the choir (pun absolutely intended). Yes, service programs and support groups are extremely valuable, and I’ll discuss this later on. But education campaigns are intended to develop empathy in those who do not understand or identify with the pain of mental illness. That’s why I believe it is important to offer these types of discussions in prime-time settings. Don’t relegate the discussion of mental illness to a time slot that will miss the majority of your parishioners. Bring the discussion into the light. By talking about this topic during a traditional worship service that involves all church members—both the sufferers and those who are not afflicted—you remove the guilt and stigma attached to mental illness and chip away at the secrecy that prevents many from seeking help. These programs will only make monumental change within the Christian community if they are offered to both those who are suffering and those who are not.

Jesus came to this Earth to be one with us, His believers. Let your congregations learn how to be one with those who are afflicted with mental illness.

Solution 3: Churches shouldn’t feel the need to treat the mentally ill themselves, but should instead be able to connect the suffering with adequate resources and support. Church leaders say they often avoid discussions about mental illness because they are unequipped to treat those who are suffering.

No kidding!

The mentally ill don’t come to your churches to be treated. They come to feel loved. And validated. And important in the eyes of God.

Your job is not to treat the mentally ill. The role of the Christian church is not a treatment facility. The role of the Christian church is a mission of advocacy. Find those who are hurting—and then find them the help they need.

Pastors, church leaders, and congregation members—you do not have an obligation to treat the mentally ill, nor should you attempt to without proper training. You do, however, have an obligation to help these sufferers find appropriate treatment. God calls you to serve, and this is service.

I believe all churches should be well-connected throughout their communities. With medical doctors, and financial planners, and business owners, and educators, and, yes, mental health professionals. So, when a mentally ill brother or sister walks into your church and asks for help, your answer should not be “Sorry about your luck—I don’t have a degree in that.” Your answer should be “I’m sorry that you’re suffering. Let’s work together to find you someone who can help.”

Churches can play a more prominent role in the battle against mental illness if they are able to connect those who are suffering with mental health counselors who might be able to counsel them, diagnose their problem, help them find medical treatment, or create a plan to avoid further pain. Churches can be the conduit through which those individuals find their remedies. Churches can help locate these counselors, make calls with nervous individuals to schedule appointments, pay for co-pays or fees, and a whole host of other compassionate behaviors that Jesus Christ encourages us to live out.

Start small, my friends. Maybe it’s just creating a list of mental health professionals in your community that you can give to someone if they are suffering. That could be the difference between life and death for the person who receives it. Whatever it is, don’t feel the need to be the treatment. Understand your role as the path to treatment, and live it out in each and every interaction.

Solution 4: Churches must build trust among smaller circles in an effort to unify the entire congregation in community. Can you imagine sharing your mental illness in front of your entire congregation? Probably not. But could you imagine sharing it within a small group of fellow believers whom you trust implicitly? Christian community can be found in large groups, but I think it’s often found in smaller, more personal settings.

We don’t have to share our struggles with the entire congregation. We should, however, have small communities and circles within our larger church families where we can share the deepest and darkest corners of our souls with one another.

It’s time for the Christian church to begin normalizing and validating the hurt and pain experienced by those with mental illness. Support groups go a long way in this effort.

In order to normalize the prevalence of mental illness, people who walk into our churches shouldn’t feel like they are the only ones who are suffering. In order to make that happen, we have to show those who are hurting that, yes, Christians suffer too.

Although education and awareness campaigns should reach the entire church (both those who are suffering and those who are not), support groups should be more insular and more safe. Support groups should be a safe haven for the mentally ill to gather with other believers, let their guard downs, and feel a sense of companionship in their similar struggles. Just as churches might offer support groups for grieving widows, divorcees, or singles, churches should create a venue for men and women with similar struggles to come together and share their burdens.

These support groups, ideally, will serve as the baby steps to open a church-wide conversation about mental illness, vulnerability, and common suffering. To expect someone to go from unspoken prayer request to congregation-wide confession is unreasonable. Instead, we should give our parishioners incremental opportunities to strengthen their resolves and experiment with vulnerability. You don’t have to share your struggles with the entire church to achieve Christ-like community.

Remember this: Jesus shared many teachings with everyone he encountered, but he chose to be the most vulnerable with a small group of only 12 ordinary men.

Solution 5: Including but not limited to mental illness, the Christian church must create a culture of openness free of judgment. Mental illness is unique, but it also shares many of the same tendencies with other worries and self-perceived weaknesses. And it’s finally time for the church to say that weaknesses are built into God’s plan. Weaknesses are natural.

How many times have you gone to church in your Sunday best after accumulating the woes and baggage of your Monday-through-Saturday worst? How many times have you sat in the pew, feeling like life could fall apart at any moment? How many times have you walked through the church doors with a smile on your face and the weight of the world weighing on your heart? You’re worried about your job, your finances, your home, your family, your self-image, and everything that comes along with life on this planet. Then, a fellow worshiper walks up to you with a smile on their face and says “Hi! How are you today?”

And with all this weight and all these burdens, you answer “I’m doing good!”

I’ve done it. I still do. And I feel like a coward every single time.

Brothers and sisters, I ask you this—if we can’t be broken in the church, where can we be broken? If it’s not safe to be vulnerable in the house of God, then just where else do we go? If I can’t go to church and feel that it’s okay to not be okay, where else should I turn?

There should be a directive on every church door in America that reads “Leave your mask at home.”

It’s time for the church to do more than open our doors. It’s time for the church to open our eyes, our ears, and most importantly our hearts.

So, we must actively monitor our reactions when people share their struggles. We must eliminate the judgmental looks and side conversations that arise when someone mentions they are suffering from depression or anxiety or suicidal thoughts.

This one is a little more simple with less concrete steps, but this is how I approach it. I think we should react to people sharing their hurts, fears, and shortcomings the same way Jesus would have reacted. If someone shared a deep hurt, do you think Jesus would have casted them a judgmental look in return? Would he have turned around and gossiped with the disciples and betrayed that person’s trust? Would he encourage that person to just “snap out” of their sin?

Or would Jesus hug that person? Would he cry with them? Would he tell them that there are ways to overcome their sickness? Would he walk next to them and protect them? Would he tell them that even in the midst of the darkest storms, God still loves them?

That’s the Jesus I know. That’s the Jesus I love. And that’s the Jesus I serve.

So, the easiest solution is this: We should treat the mentally ill the way Jesus treats them. With unconditional love, unrelenting compassion, and unbelievable fellowship.

I’ve often thought about what I would want the church to look like if I could make all my wishes and solutions come true. I’ve thought about the stances and actions I’d like to see the church take. And all this thinking brings me right back to where I started…

I’d love to go to church and never hear the phrase “unspoken prayer request” ever again.

I would love to be able to walk into a church and say “You know, I’ve been struggling with the weight of anxiety this week.” Or “I feel like I’m just not quite myself, and I don’t know why.” I long for the day when anyone suffering from mental illness could freely voice their concerns without judgement or undue criticism.

And I’m committing to the fight.

The church must speak, and we are the church.

Are you ready to start talking?

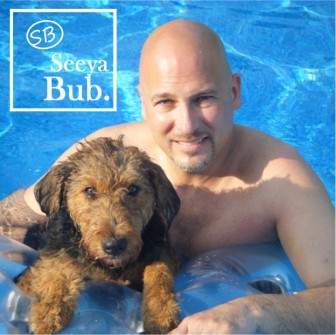

Dad, Although I miss you terribly, I am envious that you are living in the absolute perfection of heaven where all your pain is gone. I know that you are now in a perfect relationship with God—the one that he intended when he created mankind. I hope that I can find the strength to bring this world as close to that perfection as humanly possible. I think about all the times that I didn’t support you when you were suffering the way I should have, and for that I will always be sorry. But, I’m doing my best to make up for my shortcomings. I’m trying to be to others what I wish I would have been to you all along. Dad, I wish I could have created a place where you felt it was okay to admit that you weren’t feeling well and that you were hurting. I promise to make that a reality for all those who are still suffering. And I’ll honor your memory all along the way. Until I can see you and tell you all these things face to face, I’ll always love you. Seeya, Bub.

Dad, Although I miss you terribly, I am envious that you are living in the absolute perfection of heaven where all your pain is gone. I know that you are now in a perfect relationship with God—the one that he intended when he created mankind. I hope that I can find the strength to bring this world as close to that perfection as humanly possible. I think about all the times that I didn’t support you when you were suffering the way I should have, and for that I will always be sorry. But, I’m doing my best to make up for my shortcomings. I’m trying to be to others what I wish I would have been to you all along. Dad, I wish I could have created a place where you felt it was okay to admit that you weren’t feeling well and that you were hurting. I promise to make that a reality for all those who are still suffering. And I’ll honor your memory all along the way. Until I can see you and tell you all these things face to face, I’ll always love you. Seeya, Bub.

“For this reason, take up all the armor that God supplies. Then you will be able to take a stand during these evil days. Once you have overcome all obstacles, you will be able to stand your ground.

“So then, take your stand! Fasten truth around your waist like a belt. Put on God’s approval as your breastplate. Put on your shoes so that you are ready to spread the Good News that gives peace. In addition to all these, take the Christian faith as your shield. With it you can put out all the flaming arrows of the evil one. Also take salvation as your helmet and God’s word as the sword that the Spirit supplies.

Pray in the Spirit in every situation. Use every kind of prayer and request there is. For the same reason be alert. Use every kind of effort and make every kind of request for all of God’s people.” Ephesians 6:13-18 (GW)

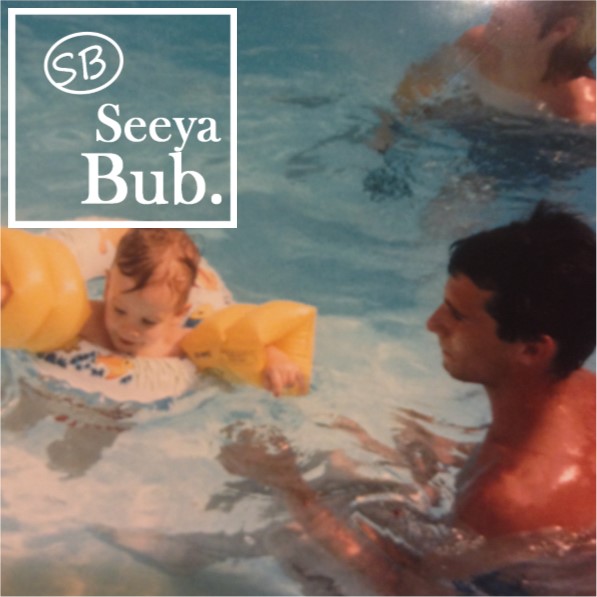

Dad, I hate that I ever had to say goodbye to you. It’s been four years since I said goodbye to you for the last time here on this Earth. I feel the pain of losing you each and every day. I would give absolutely anything to have you back, even if only for a day. For 26 years, you were always here for me, and now that you aren’t I feel the awful heartache of losing you. But I know that I could only feel that heartache because you touched my heart in ways no one else could. You taught me so many important lessons in this life, but more than anything you taught me that love matters above all else. In every moment of every day, I never doubted your love for me, for my Mom, for our family, and to all who mattered to you. You didn’t just tell people that you loved them, you showed them. And I’m thankful for that. The days stretch on without you, Dad. There are days, like today, when it’s all I can do to get out of bed at the thought of losing you. But I know that all of the wonderful moments we shared in our time together here will be completely outshined by the life we will live together in the glory of God’s grace. Thank you, Dad, for everything. I’ll never be able to tell you how much I loved you, but until that day when I try, seeya Bub.

Dad, I hate that I ever had to say goodbye to you. It’s been four years since I said goodbye to you for the last time here on this Earth. I feel the pain of losing you each and every day. I would give absolutely anything to have you back, even if only for a day. For 26 years, you were always here for me, and now that you aren’t I feel the awful heartache of losing you. But I know that I could only feel that heartache because you touched my heart in ways no one else could. You taught me so many important lessons in this life, but more than anything you taught me that love matters above all else. In every moment of every day, I never doubted your love for me, for my Mom, for our family, and to all who mattered to you. You didn’t just tell people that you loved them, you showed them. And I’m thankful for that. The days stretch on without you, Dad. There are days, like today, when it’s all I can do to get out of bed at the thought of losing you. But I know that all of the wonderful moments we shared in our time together here will be completely outshined by the life we will live together in the glory of God’s grace. Thank you, Dad, for everything. I’ll never be able to tell you how much I loved you, but until that day when I try, seeya Bub.

Dad, There isn’t a single day that goes by when I don’t think about you, but on Father’s Day I miss you even more. You were everything a Father should be. You taught me so much about life and how to live it, but I think the true testament to your life is that you’re still teaching me what it means to be a great man even after your gone. I learned something from you every day when you were here with us, and I’m still learning something from you every single day as I think back over the life you led. Dad, there were so many Father’s Days that I would redo if I had the option. There are so many moments and things I said (or didn’t say) that I would take back and change if I had the ability to do it. I wish that I had made you feel as special as you truly were on every Father’s Day and every other day. You deserved more, because you were the most loving, thoughtful, caring, and generous man I’ve ever known. And although I feel so much hurt when I can’t celebrate Father’s Day with you now, I rest easy knowing that we will get to celebrate together again someday, together with our Heavenly Father. Thank you, Dad. Thank you for everything. I’ll never be able to say thank you enough for all you’ve given me in this life. Happy Father’s Day, Bub.

Dad, There isn’t a single day that goes by when I don’t think about you, but on Father’s Day I miss you even more. You were everything a Father should be. You taught me so much about life and how to live it, but I think the true testament to your life is that you’re still teaching me what it means to be a great man even after your gone. I learned something from you every day when you were here with us, and I’m still learning something from you every single day as I think back over the life you led. Dad, there were so many Father’s Days that I would redo if I had the option. There are so many moments and things I said (or didn’t say) that I would take back and change if I had the ability to do it. I wish that I had made you feel as special as you truly were on every Father’s Day and every other day. You deserved more, because you were the most loving, thoughtful, caring, and generous man I’ve ever known. And although I feel so much hurt when I can’t celebrate Father’s Day with you now, I rest easy knowing that we will get to celebrate together again someday, together with our Heavenly Father. Thank you, Dad. Thank you for everything. I’ll never be able to say thank you enough for all you’ve given me in this life. Happy Father’s Day, Bub.

Dad, Each day I wrestle with telling your story and making sure people who never knew you know the type of man you were. I want them to know you were strong. I want them to know you were thoughtful. I want them to know you were caring and loving and everything a Father should be. I hope that the words I choose to use convey the love I have for you and the love you gave to all of us each and every day here on Earth. You never inflicted pain with the words you chose. You built people up by telling them and showing them how important they were to you. You and I had many wonderful conversations together, and we shared so many words. I’m sorry for the moments that my words may have hurt you. I wish I had spent more time telling you the words you deserved to hear—that I loved you, that I was proud of you, and that I was always there to listen when you were hurting. I know that we will have these conversations again. I wait longingly for that day. But until our words meet each other’s ears again, seeya Bub.

Dad, Each day I wrestle with telling your story and making sure people who never knew you know the type of man you were. I want them to know you were strong. I want them to know you were thoughtful. I want them to know you were caring and loving and everything a Father should be. I hope that the words I choose to use convey the love I have for you and the love you gave to all of us each and every day here on Earth. You never inflicted pain with the words you chose. You built people up by telling them and showing them how important they were to you. You and I had many wonderful conversations together, and we shared so many words. I’m sorry for the moments that my words may have hurt you. I wish I had spent more time telling you the words you deserved to hear—that I loved you, that I was proud of you, and that I was always there to listen when you were hurting. I know that we will have these conversations again. I wait longingly for that day. But until our words meet each other’s ears again, seeya Bub.

Dad, I still remember that Saturday afternoon when you and Mom gave me the new Envoy for graduation. I remember the smile on your face when you saw me come outside. I remember that you took so many pictures, and I remember how happy you were to show me every detail and feature the car had to offer. I cherished that car and I will always cherish that day. You made that entire day so special, but more than any tangible gift you ever gave me, you always told me how proud you were of me. I never told you how much confidence that gave me and how your belief in me helped me overcome so many obstacles. After you left, there were so many days where I would just hop in the car, drive down the road, and reminisce about the day you gave it to me. You blessed me with so many gifts in this life, and I am eagerly waiting for the day when I can see you and thank you again. Until then, seeya Bub.

Dad, I still remember that Saturday afternoon when you and Mom gave me the new Envoy for graduation. I remember the smile on your face when you saw me come outside. I remember that you took so many pictures, and I remember how happy you were to show me every detail and feature the car had to offer. I cherished that car and I will always cherish that day. You made that entire day so special, but more than any tangible gift you ever gave me, you always told me how proud you were of me. I never told you how much confidence that gave me and how your belief in me helped me overcome so many obstacles. After you left, there were so many days where I would just hop in the car, drive down the road, and reminisce about the day you gave it to me. You blessed me with so many gifts in this life, and I am eagerly waiting for the day when I can see you and thank you again. Until then, seeya Bub.

Ty: Dad, you would have loved spending time with Jeff, and more importantly I’m confident that he would have been able to help you find a level of peace and comfort in the midst of your depression. I have many regrets in this life, but one of my biggest is that I didn’t encourage you to go seek professional help more vigorously. I know that his style of counseling is something that would have resonated with you. I know that you would have been comfortable talking to him, and I have no doubt that you would have befriended him, just like you did with nearly everyone you crossed paths with. I wish that, as a family, we could have found a way to make you more comfortable with the idea of counseling. But, I find peace in the fact that you are now in a place where you no longer experience the pain of depression. You are living in a beautiful paradise with our Maker in a land where the trials of this world are long forgotten. I long to see you experience this peace, but until then, seeya Bub.

Ty: Dad, you would have loved spending time with Jeff, and more importantly I’m confident that he would have been able to help you find a level of peace and comfort in the midst of your depression. I have many regrets in this life, but one of my biggest is that I didn’t encourage you to go seek professional help more vigorously. I know that his style of counseling is something that would have resonated with you. I know that you would have been comfortable talking to him, and I have no doubt that you would have befriended him, just like you did with nearly everyone you crossed paths with. I wish that, as a family, we could have found a way to make you more comfortable with the idea of counseling. But, I find peace in the fact that you are now in a place where you no longer experience the pain of depression. You are living in a beautiful paradise with our Maker in a land where the trials of this world are long forgotten. I long to see you experience this peace, but until then, seeya Bub. Jeffrey Yetter, M.Ed., LPCC

Jeffrey Yetter, M.Ed., LPCC

Dad, I know that there were so many times when I didn’t understand why you would tell me to slow down, but now it all makes sense. I look back on the moments when you were happiest here in this life, and it seemed to be the moments when you were unplugged, disconnected, and severed from all the chatter and distraction that we think is important. You found what was really important in life, and you embraced it head on. You found ways to enjoy the beauty and simplicity of God’s creation, and you found a state of quietude that led to happiness and rest. I’m striving to be like you in so many ways, Dad, but I’m working especially hard on slowing down. You’d be proud to know that I still drive a little fast, just like you, but I’m slowing down to enjoy the things that were important to you and are important to me. Until we can enjoy them together in heave, I’ll seeya, Bub.

Dad, I know that there were so many times when I didn’t understand why you would tell me to slow down, but now it all makes sense. I look back on the moments when you were happiest here in this life, and it seemed to be the moments when you were unplugged, disconnected, and severed from all the chatter and distraction that we think is important. You found what was really important in life, and you embraced it head on. You found ways to enjoy the beauty and simplicity of God’s creation, and you found a state of quietude that led to happiness and rest. I’m striving to be like you in so many ways, Dad, but I’m working especially hard on slowing down. You’d be proud to know that I still drive a little fast, just like you, but I’m slowing down to enjoy the things that were important to you and are important to me. Until we can enjoy them together in heave, I’ll seeya, Bub.