Both my credit card statement and the ever-tightening waistbands on all of my dress pants will confirm one thing about me: I love Cracker Barrel…possibly, a little too much.

In many respects beyond my diet, I’m a 65 year old man trapped in the body of a 30 year old (although my physique is also more resembling of that elderly man than the young one…). Old men like television game shows. I’ve probably seen every episode of Family Feud that’s ever been recorded, and I definitely scream answers at the television and claim I would be a better contestant than…just about anyone. Old men hate it when kids are on their lawns. I am in a never-ending battle with the young neighborhood whippersnappers who think that my corner lot is public congregation space when they get off the bus. A privacy wall is coming.

One look around in any Cracker Barrel will show you that old men love it…and so do I.

I can get breakfast anytime of the day I want to. They have a fireplace. They have rocking chairs and a checkerboard. They have pancakes and fried chicken and hashbrown casserole and everything that is bad for you. And if that weren’t enough, I can eat all of those foods at once and still go buy a bag of old fashioned candy and some ridiculous house decoration that I don’t need right in the lobby!

I think America just needs a little more Cracker Barrel to solve all of our problems.

Just last week, I had some downtime and decided to make a stop at Cracker Barrel for breakfast with the intent of ordering something moderately healthy. An order of cinnamon streusel French toast and bacon later (I said “intent”), I found myself scanning the restaurant because Cracker Barrels are the absolute best for people watching.

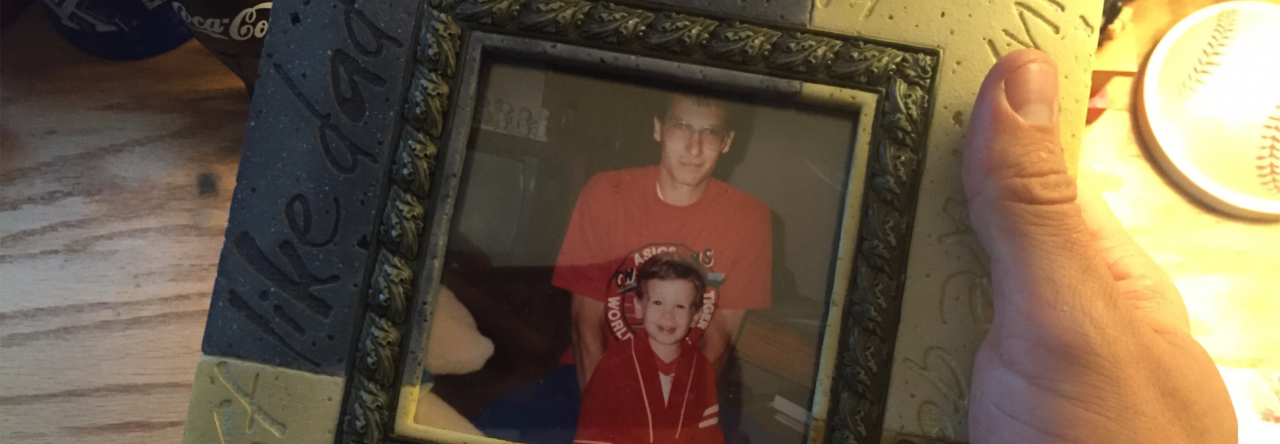

My eyes settled in on the table right next to me. It was a Father and his young (probably 5 or 6 year old) son. My heart sank, but it always does that when I see a father and son. It’s happened ever since Dad died. No matter where I am, if I see a dad and a son out together by themselves, it draws me back to what I don’t have. It reminds me of what I miss most. It makes me wish my Dad was still here.

This particular young boy immediately grabbed me because he was just a cute kid. He wore a flashy Under Armour hoodie and some cool tennis shoes. He had a toothy grin, freckles, and enough gel in his hair to spike up his light brown bangs. He had a gray bubble coat draped across the back of his chair, and he smiled at me when our eyes connected.

I looked across my own table and saw an empty seat—the spot where my Dad should have been sitting. My mind went back to all the times that he and I and Mom had sat at Cracker Barrel tables together—Dad always ordering chicken and dumplings, but always making time for a quick game of checkers by the fireplace before the food came out.

I see that empty seat quite often, and it makes me nauseous. I’ll immediately feel myself tearing up, and I often have to tell myself that I need to think about something else instead to fight off the waterworks. It’s not that I don’t want to think about my Dad—believe me, I do. Mostly, I just don’t want people to stare at my while I’m getting upset at a table by myself.

So, on this particular day, I decided to focus on the boy and his Dad sitting at the table next to me. Little did I know that this would probably make me just as upset as thinking about my own Dad would have.

The boy and his Father placed their orders shortly after I did. I paid particular attention to the little boy’s order: pancakes and bacon. I knew I liked this kid.

After the waitress left, I saw something that I see way too often. The boy’s Dad, sitting at a table with just his son, given the perfect opportunity to be an engaged Father, instead decided to pull out his cell phone. Apparently, there was something more entertaining on that tiny screen than the tiny and interesting human sitting right across from him. I’ve always been bothered by sights like these, mainly because my parents always taught me that time at the dinner table was insanely precious. We always engaged with one another. Little did I know just how valuable it would be when we couldn’t have it anymore…

I watched for a few minutes, and then a few minutes more, as this Father poured every ounce of attention he had into the small phone he held in his hands. The young boy tried to engage his Dad at first, as most young boys will do, but there was no reaction. This particular Dad wanted everything to do with his phone and nothing to do with his son. Absurd.

As young boys will do, this little guy began to get restless. He would occasionally spin around and rest his chin on the back of his chair and his coat, staring at the other families around the restaurant. Before long, he jumped up from his chair and walked over to his Dad, probably to see what was so interesting on that phone of his. That’s when my fury reached a brand new level.

The Dad snapped at this cute, innocent little boy, admonishing him sharply and telling him to sit down. The look on his face was pure meanness. I have an absolutely terrible poker face, so I’m sure my jaw was dropped onto the table by this point. With a force that no young boy deserves, the Dad thrust his son back towards his chair. My heart broke as I watched the young boy’s head hanging in shame, eyes glued to the floor. He kicked his legs back and forth slowly as his face turned red, probably worried that people in the restaurant were staring at him. There are few things more uncomfortable than feeling shame as a young child. It’s debilitating. He looked like he was on the verge of tears, and so was I.

But I was more than sad at this point. I was angry. I was furious. I wanted to get up and tell this Dad off. I wanted to tell him that he had no idea how precious this time was with his son. I wanted to tell him that he should cherish every moment—every single moment—that he has with this young boy. I wanted to tell them that he won’t have these opportunities forever. I wanted to tell him that he has a God-given responsibility to instill values and character into that young boy’s mind and heart, and that he wasn’t going to do that acting like a complete and total jerk.

Somehow, I restrained myself. I clenched my fists, studied the salt shaker, and even gave the Peg game on the table a go (I’m attributing my poor score of three remaining pegs to the low blood sugar of not having yet received my French toast). I tried to ignore what was happening (or not happening) at the table next to me, but after a while, I had to look again.

There sat the little boy, chin resting on his chair back, staring at the other families in the restaurant. And there sat the father, eyes still locked-in on the mobile screen in front of him.

Finally, the Dad looked up at his son. “Finally,” I thought to myself. “It took him long enough, but he’s going to talk to the little guy. Good for him.”

“You wanna put your straw in your water?” he said.

It wasn’t profound, but I told myself it was interaction nonetheless. Baby steps.

It was amazing and a bit saddening to watch the little boy’s composure change just because his Dad recognized him. Just because his Dad finally paid a little bit of attention to him. I thought things might be looking up. With his little hands, he grabbed the paper-wrapped straw from beside his tiny cup of water. Then, he did what most youngsters will do. He began to bang the end of the straw against the table until the paper would slide off.

With a level of anger completely unwarranted by the situation, the Dad reached across the table yelling “Give me that!” from the young boy. He grabbed the straw from his little hands and opened it in a more “dignified” manner. Having opened the straw, he put it in the boy’s cup as his little eyes looked on, head hanging low once again.

Then, the Dad took things to an entirely new absurdity level. He shook his head back and forth a few times as his face began to grow red (from anger, not embarrassment) and said “I don’t understand why you do things like that.”

It took everything I had in me to not stand up from the table, bash his head with the oil lantern, and see myself expelled from every Cracker Barrel in North America. I had a few bottles of mini maple syrup, and I was pretty sure no one would have blamed me had I poured them right over this jerk’s head.

I was furious. Even more furious than this Dad was when his little boy didn’t know how to “properly” unwrap his straw.

“That’s it,” I said in my mind. “I’m saying something to this guy. He deserves it! Before I go, I’m going to tell them exactly what I think of his parenting. And he’s not that big so I can take him if he tries something funny. Or I can knock over a display of candles in the lobby and run really, really fast.”

In that moment, I looked across my own table—the empty table—and got even more upset than I had previously been. My Father was more than a father—he was a Dad. When I was little, he made me feel like I mattered. He talked to me and had conversations with me. He made me feel so important and so loved. He taught me things and was legitimately interested in me. And yes, it may have been a different time, but nothing as silly as a cell phone would have ever gotten in the way of a conversation with his son.

I got angry because my Dad was gone. I began to wallow in my own self-pity, thinking selfishly that it wasn’t fair that Dads like this still got time with their sons when Dads as deserving as mine had lost theirs way too soon. It’s a feeling I get quite often.

When the Dad and his boy finally received their food, the little boy didn’t even get any help from his Dad. He put his own syrup on the pancakes. He clumsily navigated a knife and fork to cut his pancakes into bite-size pieces. I grew even sadder watching him enjoy his little breakfast in unnecessary silence.

So, I did what I often do in moments like this. I began to talk to God. And I began to talk to Dad.

I don’t pride myself on being a theological expert, and I don’t know whether or not it’s even realistic, but when I think of what’s happening in Heaven while I’m down here on Earth, I will often picture my Dad and God standing right next to one another. Their elbows rest on a shelf of clouds, and they are looking down at me, watching over me, and encouraging me. They talk with one another. They roll their eyes when I do something foolish (there’s lots of eye rolling, by the way). They laugh at me. But more than anything, they send me lots of love from above.

The nice part of this visual is that, when times get tough and I don’t know what to do, I’ll often turn my face to the sky and simply ask them. I’ll cry out. I’ll say “Tell me what I should do here. I need you. I need you both.”

And that’s exactly what I did. In the middle of a Cracker Barrel, I looked upwards with my palms facing skyward on the wooden table, and mouthed the words “Tell me what you want me to do here, because I’m lost and I’m angry.”

I expected them to tell me to get courageous. To harden my resolve. That it was time for me to stand up for what I believed in. That I needed to be a man, tell this guy that he needed to be a man too, and walk out with my shoulders back and my head held high. I waited eagerly for their response, and I nearly threw up my French toast when I heard it.

“Ask for their check,” was what I heard. “Ask for their check,” was what came to my mind.

Apparently, people in Heaven are perfect but can still say crazy things.

My eyes must have been as wide as cornbread muffins as I stared across the table at the empty chair opposite me. My mouth was agape, and I was beginning to sweat a little bit. I looked at the spot where my Dad should’ve been sitting, and I told him exactly what I thought about his suggestion: “That’s probably your dumbest idea yet.”

I was angry that this was the solution that came into my mind. I was mad that this was the best solution that the Lord of all mankind and my Dad could come up with. I wasn’t about to reward bad behavior. I wasn’t going to give this guy any of my hard-earned money as he sat there and wasted the best gift he could have ever received—a relationship with his son. No way. I’m sorry, God. I’m sorry, Dad. It’s not happening. Try again.

But the phrase just kept coming back to me. “Ask for their check. Ask for their check. Ask for their check.” Over and over again I kept hearing this phrase. No matter how hard I fought it, it was like God and my Dad were telling me that there was no other way out. There was no other solution to what was happening in that moment. I knew this was a spiritual test, but I also knew it was bigger than that.

I asked God to tell me why. I asked God to explain to me why this was His solution. He didn’t tell me straight out, but He gave me some wisdom to think through this. And I knew that it was wisdom that both God and my Dad would appreciate.

First and foremost, I reminded myself that I was only seeing a snapshot of this family’s life. I hoped it didn’t get worse than this, but I had no idea what their morning had been like. I had no idea of this man’s story or anything he was dealing with at the time. I didn’t know what brought him to that table on that morning, what things were weighing on his heart, or the insecurities he might have been feeling as a father in that moment.

Then, I thought of my Dad. I thought of the types of things he would have done. My Dad was the type of man to pick up someone’s check. My Dad was the type of person to not judge people, even if he didn’t like their actions. My Dad gave people the benefit of the doubt in every circumstance, even when they upset him. My Dad was a giver, and he believed that you could teach people more through kindness as opposed to anger, retribution, and holy discipline. My Dad was a big fan of New Testament love. I was a fan of Old Testament fire and brimstone.

I also remembered something that I saw my Dad live out many, many times during his 50 years here on this Earth. Little actions of love can have big, lasting implications. Little interactions that show kindness can change a life and many more. Little moments of tenderness can spread like wildfire. Maybe, just maybe, I would pay this man’s check. And maybe, just maybe, it would put him in a good mood and change how he interacted with his son on that day. And maybe this little boy, who deserved it, would have a good day. And that good day would lead to other good days and a different relationship between these two. It was stupidly optimistic…and it was exactly the type of thing my Dad would have believed.

I did what I thought was unthinkable. I called upon the Holy Spirit to help me, and summoned some courage from my Dad. When the waitress came by, I signaled her, leaned over, and said to her… “Can I ask you for a Diet Coke to go?”

Just kidding. I said “Can I ask you for a Diet Coke to go? And, also, can you bring me their check without letting them see it?” I nodded towards their table.

“You want the check for the little boy’s table?” she responded.

“Yes, ma’am,” I said, feeling like a wimp. Feeling like I had lost the battle by not telling this man exactly what I thought of him.

“Absolutely,” she said with a huge smile across her face. She returned a few minutes later with a Diet Coke (I felt I deserved this much) and a check a few times larger than the one I had originally received.

I grabbed it, got up from the table, and walked past the man and his son.

As was expected, the Father was a bit too enamored with his chicken fried steak to notice me. But I didn’t want to look at him anyway. I looked at the boy. The little boy with the hoodie and the hair gel and the pancakes. He looked at me and I smiled and winked, walking out of the restaurant without saying a word. I paid my bill. Then I paid for their bill. I grabbed my to-go cup, walked out of the Cracker Barrel towards my car, and looked up towards the sky.

“There. Are you two happy?” I said begrudgingly.

I imagined that both God and Dad were smiling down nodding their heads yes, and laughing that I could get so frustrated showing love to someone else.

While I sat in my car, I began to cry a bit, feeling the emptiness of not having my Dad here with me. But it’s moments like these that remind me that he is always here. That his memory can live on each and every day, as long as I live my life the way he would have. His life and legacy live on in my heart. I know I’ll never be the man that my Dad was. The bar is just too high. But I’ve accepted that. I’d rather aim high and miss a little lower, though, than not try at all. It’s my duty to my Dad to do the things he would have done. If he can’t be here to do them, I need to be the one to live like my Dad. I didn’t pay the bill on that day. My Dad did.

I pray that my Dad’s gesture made that little boy’s day a little better. And I pray that it warmed that Dad’s heart. And I desperately hope that they had a wonderful day together. I mean…it started at Cracker Barrel so how could it be bad?!

I thank my Dad for inspiring me to do things in moments like that. I thank my Dad for helping to change my heart. Initially, I had hoped this man would choke a bit on his chicken fried steak, and just a few minutes later I was paying for his meal. Well played, Dad. Well played.

And, more than anything, I pray that for as long as I live, my Dad keeps guiding me. That he keeps giving me instructions. That he keeps forcing me to do things I would never, ever do on my own.

I’m a better man because my Dad was here for 26 wonderful years, and I’ll be a better man because he will always be in my mind and in my heart for as long as I live.

And next time, I’ll try a bit harder to order the fruit and yogurt.

Dad, Even though you’re not here with me, I know you’re always with me. I know you’re always watching over me and guiding me and pushing me to be a better Christian. On the days when I feel sad that you’re not around, it’s always moments like this one that remind me that you’ll never leave. Yes, we haven’t talked face to face since that horrible July day in 2013; but I feel like we’ve been talking ever since. Little things happen in my life that allow your memory to shine through, and I’m so grateful for that. Dad, you would be so proud to know that your story is inspiring people to live better lives. You have no idea how many people miss you and love you and wish you were here. Remind them, and remind me, that you’re always here as long as we live life the way you did. Remind us all that love is more important than absolutely anything. I’m reminded each and every day how much I love you. Thank you for teaching me what it means to be a Father. Thank you for giving your entire self to me. And thanks for never taking it easy on me when we played checkers. I love you Dad, and I miss you terribly. Until we can share a seat at a table even better than one at Cracker Barrel, seeya Bub.

Dad, Even though you’re not here with me, I know you’re always with me. I know you’re always watching over me and guiding me and pushing me to be a better Christian. On the days when I feel sad that you’re not around, it’s always moments like this one that remind me that you’ll never leave. Yes, we haven’t talked face to face since that horrible July day in 2013; but I feel like we’ve been talking ever since. Little things happen in my life that allow your memory to shine through, and I’m so grateful for that. Dad, you would be so proud to know that your story is inspiring people to live better lives. You have no idea how many people miss you and love you and wish you were here. Remind them, and remind me, that you’re always here as long as we live life the way you did. Remind us all that love is more important than absolutely anything. I’m reminded each and every day how much I love you. Thank you for teaching me what it means to be a Father. Thank you for giving your entire self to me. And thanks for never taking it easy on me when we played checkers. I love you Dad, and I miss you terribly. Until we can share a seat at a table even better than one at Cracker Barrel, seeya Bub.

“But love your enemies, do good to them, and lend to them without expecting to get anything back. Then your reward will be great, and you will be children of the Most High, because he is kind to the ungrateful and wicked.” Luke 6:35 (NIV)

Dad, When I think of the things you enjoyed, I always think of bonfires. They provided you with such amusement, but deep down I think they also provided you with a lot of peace. Your mind and soul just seemed to be quieter and happier when you were sitting around a good fire. I wish I could take back all of those days when you’d ask me to come sit with you and I said no. I wish I had spent more time with you around the fire, but there never would have been enough time with you because you made life so exciting and full of love. It may not be around a fire, but I’ll spend more time with those I love because I realize that I should have spent more time with you when I had the chance. I love you, Dad. I miss you like crazy, although I don’t miss the constant bamboo explosions. Okay, who am I kidding…of course I miss those. Thanks for all the fires we did share, but more importantly thanks for keeping the fire in my heart going even after you’re gone. I’m looking forward to that first bonfire together on the other side…I’ll bring the flamethrower. But for now, seeya Bub.

Dad, When I think of the things you enjoyed, I always think of bonfires. They provided you with such amusement, but deep down I think they also provided you with a lot of peace. Your mind and soul just seemed to be quieter and happier when you were sitting around a good fire. I wish I could take back all of those days when you’d ask me to come sit with you and I said no. I wish I had spent more time with you around the fire, but there never would have been enough time with you because you made life so exciting and full of love. It may not be around a fire, but I’ll spend more time with those I love because I realize that I should have spent more time with you when I had the chance. I love you, Dad. I miss you like crazy, although I don’t miss the constant bamboo explosions. Okay, who am I kidding…of course I miss those. Thanks for all the fires we did share, but more importantly thanks for keeping the fire in my heart going even after you’re gone. I’m looking forward to that first bonfire together on the other side…I’ll bring the flamethrower. But for now, seeya Bub.

Dad, I have such fond memories of my childhood because you and Mom always made them so special. I remember all the wonderful trips we went on together, and I remember all of the things we used to do together that made those moments so memorable. I loved mining for rocks when I was little, and as nerdy as it might have been, you always encouraged me and kept the excitement at an all-time high. Dad, there were so many things I wish we could have had the opportunity together. I hate that we can’t do them now, but I am thankful that I’m able to remember you simply by grabbing a rock off of the ground. You are an amazing Father, both in life and in death, because you always made life worth living and you left an impression on everyone who knew you. Thank you, Dad, for always being my rock. Thank you for giving me the love I needed every day. Until I can thank you in person, seeya Bub.

Dad, I have such fond memories of my childhood because you and Mom always made them so special. I remember all the wonderful trips we went on together, and I remember all of the things we used to do together that made those moments so memorable. I loved mining for rocks when I was little, and as nerdy as it might have been, you always encouraged me and kept the excitement at an all-time high. Dad, there were so many things I wish we could have had the opportunity together. I hate that we can’t do them now, but I am thankful that I’m able to remember you simply by grabbing a rock off of the ground. You are an amazing Father, both in life and in death, because you always made life worth living and you left an impression on everyone who knew you. Thank you, Dad, for always being my rock. Thank you for giving me the love I needed every day. Until I can thank you in person, seeya Bub.

Dad, There are so many days when I wish I could snap my fingers and have my old life back. The life when you existed here on Earth. I wish that I could have lunch with you, or go on a bike ride, or listen to country music together, or sit by the bonfire. I wish I could hear your laugh again. I wish I could feel you rub my head when you left for work in the morning. I wish that these memories weren’t memories, but instead were real life. But I know life is difficult, and I am amazingly grateful that I can look back over the twenty-six years we spent together and know that you gave every ounce of love you had, each and every day. Ironically, you being in my life prepared me to live life without you. You taught me to enjoy life in spite of hard circumstances or difficult moments. When times get tough, especially when I think about losing you, I’m able to resort to the things you taught me. I’m able to remember the appreciation you had for life’s little moments. And I smile. Sometimes through tears, but I’m smiling nonetheless. I have you to thank for that smile, and so much more. Until I can thank you again in person and experience a new Dad Day that will last through eternity, seeya Bub.

Dad, There are so many days when I wish I could snap my fingers and have my old life back. The life when you existed here on Earth. I wish that I could have lunch with you, or go on a bike ride, or listen to country music together, or sit by the bonfire. I wish I could hear your laugh again. I wish I could feel you rub my head when you left for work in the morning. I wish that these memories weren’t memories, but instead were real life. But I know life is difficult, and I am amazingly grateful that I can look back over the twenty-six years we spent together and know that you gave every ounce of love you had, each and every day. Ironically, you being in my life prepared me to live life without you. You taught me to enjoy life in spite of hard circumstances or difficult moments. When times get tough, especially when I think about losing you, I’m able to resort to the things you taught me. I’m able to remember the appreciation you had for life’s little moments. And I smile. Sometimes through tears, but I’m smiling nonetheless. I have you to thank for that smile, and so much more. Until I can thank you again in person and experience a new Dad Day that will last through eternity, seeya Bub.

Dad, Although I miss you terribly, I am envious that you are living in the absolute perfection of heaven where all your pain is gone. I know that you are now in a perfect relationship with God—the one that he intended when he created mankind. I hope that I can find the strength to bring this world as close to that perfection as humanly possible. I think about all the times that I didn’t support you when you were suffering the way I should have, and for that I will always be sorry. But, I’m doing my best to make up for my shortcomings. I’m trying to be to others what I wish I would have been to you all along. Dad, I wish I could have created a place where you felt it was okay to admit that you weren’t feeling well and that you were hurting. I promise to make that a reality for all those who are still suffering. And I’ll honor your memory all along the way. Until I can see you and tell you all these things face to face, I’ll always love you. Seeya, Bub.

Dad, Although I miss you terribly, I am envious that you are living in the absolute perfection of heaven where all your pain is gone. I know that you are now in a perfect relationship with God—the one that he intended when he created mankind. I hope that I can find the strength to bring this world as close to that perfection as humanly possible. I think about all the times that I didn’t support you when you were suffering the way I should have, and for that I will always be sorry. But, I’m doing my best to make up for my shortcomings. I’m trying to be to others what I wish I would have been to you all along. Dad, I wish I could have created a place where you felt it was okay to admit that you weren’t feeling well and that you were hurting. I promise to make that a reality for all those who are still suffering. And I’ll honor your memory all along the way. Until I can see you and tell you all these things face to face, I’ll always love you. Seeya, Bub.

Dad, Since the time I was a little boy, you always taught me the importance of my relationship with Jesus. But you always taught me that my relationship with Jesus always needed to be reflected in my relationship with other people. I can’t imagine how many times we must have went to church together when you were hurting more than I ever knew. I wish I knew what to do then. I hope that I know what to do now. I’m trying my hardest to change the world around me, to make it a better place for those who are suffering like you did. Thank you for giving me a lifetime of inspiration, Dad. I’ll never get over losing you, but until we are together again, seeya Bub.

Dad, Since the time I was a little boy, you always taught me the importance of my relationship with Jesus. But you always taught me that my relationship with Jesus always needed to be reflected in my relationship with other people. I can’t imagine how many times we must have went to church together when you were hurting more than I ever knew. I wish I knew what to do then. I hope that I know what to do now. I’m trying my hardest to change the world around me, to make it a better place for those who are suffering like you did. Thank you for giving me a lifetime of inspiration, Dad. I’ll never get over losing you, but until we are together again, seeya Bub.

Dad, Even though I know you would tell me not to feel regret, I do wish that I had the chance to hit the “do-over” button on so many things in my life. I wish I had been more of a support to you when you needed me. I wish that I had spent more time with you doing the things you loved to do. I wish that I could have done more to help you find peace and solace in the tumult of your depression. I don’t know the answer to why this terrible tragedy happened, but I do know that God has a plan to make something good out of it. I often wonder what could possibly be better than more time with you, but I know that although I feel a horrible separation from you in these moments, there will come a day when you and I can both live completely free of regret and goodbyes. I long for that day, but until then, seeya Bub.

Dad, Even though I know you would tell me not to feel regret, I do wish that I had the chance to hit the “do-over” button on so many things in my life. I wish I had been more of a support to you when you needed me. I wish that I had spent more time with you doing the things you loved to do. I wish that I could have done more to help you find peace and solace in the tumult of your depression. I don’t know the answer to why this terrible tragedy happened, but I do know that God has a plan to make something good out of it. I often wonder what could possibly be better than more time with you, but I know that although I feel a horrible separation from you in these moments, there will come a day when you and I can both live completely free of regret and goodbyes. I long for that day, but until then, seeya Bub.

Dad, There have been so many days when life has seemed unlivable without you in it. There have been moments when I’ve completely collapsed under the weight of my own worry and troubles, and I wish more than anything that you were here to encourage me in those moments of doubt and frustration. But in a sense, you are here with me. The lessons you taught me throughout my life were always lessons of empowerment. You taught me that I am always stronger than I think I am, and that when I am weak God is strong. You also showed me that it’s okay to have feelings and emotions and that I can express those when I feel them. You showed such bravery in your life, and I hate that in your final moments you doubted your own courage. Dad, you were the most courageous man I’ve ever known. You fought so hard for so long, and I’m glad you’re not fighting anymore because that enemy that you faced is defeated once and for all. I’m so thankful that you are completely at peace, completely healed, and completely perfected in God’s love and image. Dad, you deserve eternal rest in paradise (hopefully free of snakes), but boy do I wish you were still here with me to help me in this imperfect world. Keep giving me that courage when I need it most. And until I can thank you in person, seeya Bub.

Dad, There have been so many days when life has seemed unlivable without you in it. There have been moments when I’ve completely collapsed under the weight of my own worry and troubles, and I wish more than anything that you were here to encourage me in those moments of doubt and frustration. But in a sense, you are here with me. The lessons you taught me throughout my life were always lessons of empowerment. You taught me that I am always stronger than I think I am, and that when I am weak God is strong. You also showed me that it’s okay to have feelings and emotions and that I can express those when I feel them. You showed such bravery in your life, and I hate that in your final moments you doubted your own courage. Dad, you were the most courageous man I’ve ever known. You fought so hard for so long, and I’m glad you’re not fighting anymore because that enemy that you faced is defeated once and for all. I’m so thankful that you are completely at peace, completely healed, and completely perfected in God’s love and image. Dad, you deserve eternal rest in paradise (hopefully free of snakes), but boy do I wish you were still here with me to help me in this imperfect world. Keep giving me that courage when I need it most. And until I can thank you in person, seeya Bub.

Dad, In lieu of the letter I should have written to you before you died, I have been writing letters to you ever since. Letters that share my love for you and my sadness that you are no longer here. There isn’t a single day that goes by when I don’t miss you. You writing such an honest and authentic letter to me as a young freshie is just one of the many spectacular gifts you gave me as your son. I read your words, and although they still bring tears to my eyes as they did on the first day I read it, they also bring a sense of gratitude that I had you as a Father here on earth for all the years I did. I wasn’t just lucky to have you as a Dad—I was blessed beyond belief. Your words in that letter are so important to me because I know they aren’t just words. They are reflections of your innermost beliefs, and you lived and loved me in a way that made those words come to life. Thank you for writing that letter, Dad. I’m sorry that I never wrote you the one you deserved to read. It breaks my heart knowing that I never handed you a letter in return, but it gives me hope knowing that I’ll get to tell you exactly how much I love you face to face someday. Until that wonderful day, seeya Bub.

Dad, In lieu of the letter I should have written to you before you died, I have been writing letters to you ever since. Letters that share my love for you and my sadness that you are no longer here. There isn’t a single day that goes by when I don’t miss you. You writing such an honest and authentic letter to me as a young freshie is just one of the many spectacular gifts you gave me as your son. I read your words, and although they still bring tears to my eyes as they did on the first day I read it, they also bring a sense of gratitude that I had you as a Father here on earth for all the years I did. I wasn’t just lucky to have you as a Dad—I was blessed beyond belief. Your words in that letter are so important to me because I know they aren’t just words. They are reflections of your innermost beliefs, and you lived and loved me in a way that made those words come to life. Thank you for writing that letter, Dad. I’m sorry that I never wrote you the one you deserved to read. It breaks my heart knowing that I never handed you a letter in return, but it gives me hope knowing that I’ll get to tell you exactly how much I love you face to face someday. Until that wonderful day, seeya Bub.