On most evenings (and much to my own personal dread on the cold ones), I take our golden retriever puppy, Penelope, for a walk around our neighborhood. Slowly but surely, Penny is figuring out how to walk like a respectable dog.

Let me rephrase that—very slowly, but surely nonetheless.

More and more, Penny is growing to like her walks. At first, she was always a bit too anxious and couldn’t enjoy the walks because of her nervousness. Paige and I didn’t give up, and after many failed attempts and one fantastic puppy training camp later (thanks Rhino Kennels!), Penny is getting more and more accustomed to her nighttime strolls around our corner of suburbia. She usually gives me a few excited jumps as we begin our walks together (even though I’m pretty sure our dog trainer told us not to let her do this but it really is pretty adorable—sorry Rhino Kennels!). She’s growing more interested in sniffing cars and flowers and fire hydrants along the way. And she has really enjoyed stopping at either of the ponds in our neighborhood if there happens to be a pack of geese or ducks that she can watch intently.

But even with all her progress, Penny still gets a bit nervous. Paige and I laugh about Penny’s nervous “head dip” that she does when she sees something she doesn’t recognize approaching in the distance. I can always tell when she’s spotted something coming her way. If she sees an approaching person, dog, or UWO (unidentified walking object), Penny’s pace slows ever so slightly. Her walking becomes much more deliberate and controlled. Locked in on the figure in the distance, Penny lowers her head slightly and hunches her little puppy shoulders (do puppies have shoulders?!). As we get closer and closer, Penny’s hunch gets lower and lower. Her walking slows even more until, finally, we reach the object. She either lowers her hunch all the way to the ground and stays in a submissive position, or if she’s feeling friendly, she investigates, jumps, and wags her tail.

Most of the time, I laugh at Penny—that is, until I spot something that I can’t identify on the horizon and get a little nervous myself.

My work schedule typically requires that I walk Penny in the evening, and the fantastic winter weather and daily 37-minutes of sunshine that we seem to get in southwestern Ohio at this time of year often require that I walk Penny in the dark. For the most part, our neighborhood is very well lit, but there are some stretches that tend to be a bit darker than others.

A few evenings ago, Penny and I were walking together in the cold when I noticed the familiar hunching behavior of my four-legged companion. Realizing that she had spotted something up ahead, I looked up and spotted something in the distance. I spotted it too, and after a few seconds of quick mental processing, I had identified three possible things that the darkened object on the sidewalk up ahead could have been:

- A small, toothy-little creature that was prepared to chew all of our ankles off,

- A carnivorous, vicious, prehistoric-style bird that would peck through my ribcage and ravage all of my internal organs, or

- A piece of trash.

Naturally, I chose the most realistic option of the three.

It was definitely the bird.

If you know me, you know that I have a particularly strong fear of any creature from the avian realm. I’ve got this whole ornithophobia thing down to a fear-inducing science of pure terror. When I was a child, my Dad used to torment me at the county fair by gleefully dragging me through the chicken barn as I shrieked, bawled, and prayed to my God and any others who might be listening that none of these foul fowls would decide to jump on me and peck my eyes out. When I visit Home Depot, I am that guy who ducks (no pun intended) anytime a bird flies down from the warehouse-style ceiling (WE ARE INSIDE! WHY IS A BIRD INSIDE?!). And one time while on vacation with our closest friends a few years ago, a seagull attacked me and stole the last bite of my delicious Cuban sandwich as I screamed for intervention from the Almighty. I still can’t eat a Cuban sandwich without feeling my heart rate increase. Thanks, bird.

On the night in question, as Penny and I both crept towards the vulture-like bird on the sidewalk in front of us, we each grew a bit more anxious. I could see Penny’s head go lower and lower and lower towards the ground as she slowed her walk, and I felt myself preparing for a bit of a run in the event that this bird did what I knew it was going to do (namely, kill me and my dog in a violent flurry of feathers and squawking).

A light in the distance flickered, and as we got closer and closer I decided to take out my phone and turn on the flashlight so I could look into the devilish eyes of the murderous beast. And once I cast the light up ahead of us, I had a clear vision of our dreaded enemy.

A mangled pizza box.

(But wait….there could still be a bird inside the pizza box ready to fly out and peck our eyeballs out, right?!)

That’s right. The fear-inducing figure in the distance turned out to be nothing more than someone’s old, empty pizza box that had likely blown from a garbage can down the street.

I was relieved, and so was Penny—although she really wishes there would have been a slice of pepperoni with extra cheese left for her. But it wasn’t until we were able to shine a light on the shadow in the distance and realize what it was before we could be free from our anxiety and fear.

And in many ways, I think that mental illness works the same way.

I firmly believe that mental illness is an enemy that, when left in the dark, grows stronger, more powerful, and more all-encompassing day by day. I also believe that, when talked about and brought out into the light, we diminish the stronghold that mental illness can have on our minds and on our lives. With each confession that we are struggling or hurting, we slowly strip mental illness of its power and fight against the culture of silence where it finds its control.

When I reflect and think back on my Dad’s struggle, I can see this playing out in the rearview mirror as I desperately wish I had paid more attention to it. For the longest time, my Dad refused to shine a light on his own depression, but instead chose to bury it deep below the surface—but his motivations weren’t egocentric in the slightest. My Dad was not a man who cared about image or his own ego, and I am confident that the reasons that my Dad felt he couldn’t talk about his depression were motivated by a fear of disappointment—more than most, he was afraid he would let people down.

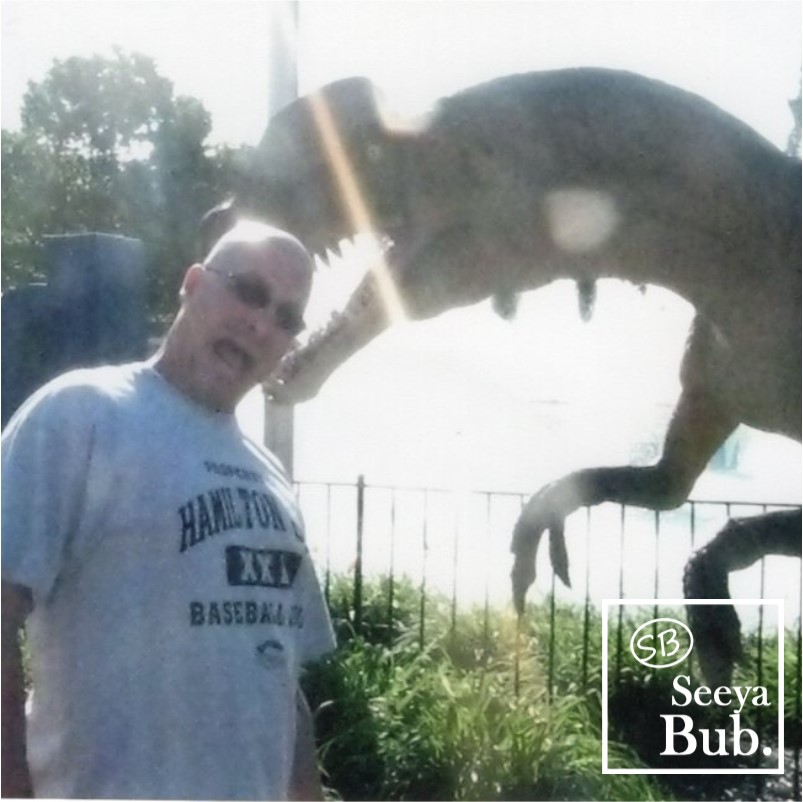

My Dad was a fixer. A builder. A carpenter, electrician, and maintenance technician by both trade and pure interest, and there was rarely a thing my Dad couldn’t do. My Dad was the guy that everyone called. If you needed a ceiling fan fixed or a shower tiled or a deck built, my Dad was the first call for many. His talents, as I’ve written about before, were abundant, and now that he’s gone, I think I’m even more in awe of what he could do. He was an artist, a craftsman of the highest order, obsessed with detail, quality, and perfection. But above all, he loved being able to make others happy with his talent. And by golly, it was genuine.

Above all, I know the motive for why my Dad helped people. It wasn’t about showing off those talents. It was never about boasting. It was because he had a fixer’s heart, and he liked being able to help others. More than anything, I think my Dad had a deep fear of disappointing people.

This fear of disappointing people was one of his most admirable qualities—but it was also the same fear that, left unchecked, led to him into periods of suffering in isolation and loneliness. Among his many great qualities, my Dad was also dependable beyond belief. If he told you he would be somewhere, he was there. If he told you he was going to fix something, it would be fixed. He held himself to a higher standard than anyone else, and that higher standard could create pressure that was difficult to reckon with. I believe that my Dad had an irrational fear that admitting he had depression and that he was suffering would cause people to think they couldn’t depend on him any longer—and I’m confident that it was that fear, more than anything, that kept him from talking about his illness.

It’s a fear that wasn’t unique to my Dad. It’s a mindset of silence that, unfortunately, is all too pervasive for those who are hurting, suffering, and struggling with mental illness.

When I reflect on my Dad’s story and think deeply about the moments when his depression controlled him most severely, it’s hard not to think of the scary and frightening moments. Those moments when, fueled by his depression, he would inexplicably leave without a trace and runaway, abandoning the home where all the comfort he ever needed lived.

But time gives the benefit of great perspective and holism, and I can simultaneously reflect on the moments immediately thereafter when he would come home, admit his defeat, and seek help. Those moments when Dad would return and when we would talk about his depression, dragging the monster that scared him out into the light to recognize it for what it was and to emphasize, strongly, that there was a path forward—to encourage and show Dad that he could manage and control this—were moments of unbelievable growth. We would recognize Dad’s depression and not deny the fact that it existed. He would visit the doctor, and be vulnerable about what was going on, and chart a path forward through medication and other treatments.

And then, with his depression called out into the open, Dad would get better. It wasn’t easy. It was never a “snap your fingers” type of treatment. It took weeks, sometimes months, for Dad to get better—but in nearly every situation, Dad did get better. And for a while (sometimes a long, long while), things would be at their best. And Dad would be at his best—a conquering fighter who would refuse to let his life be controlled by a powerful, dangerous illness.

It would be those moments when Dad’s depression was out in the open amongst our family in which he would feel most at ease—most comfortable with who he was at his core. During the times when Dad felt he could admit that he was struggling and he could avoid the shame of feeling like he needed to hide his illness, I think my Dad was truly at his happiest, his most content, and his most peaceful state.

Doesn’t it work that way for so many out there who are hurting and suffering from mental illness?

We all harbor different fears. Some of us are afraid of heights. Others are afraid of social situations. The smart people are afraid of birds. But then there are those deeper, emotionally-laden fears that are hard, even embarrassing, to talk about. Our fears of rejection. Our fears of solitude. Of financial inadequacy. Of pain and abuse. Of insecurity. And yes, of disappointment.

When we grow fearful, we often feel we have to wear a mask. And when we wear a mask, we are unnecessarily burdened by the shame of feeling that we have to hide how we feel. We shy away from honestly sharing our fears and insecurities, and as we do, those same fears and insecurities grow and grow and grow, eventually growing to a point that they take over our ability to function regularly.

But it’s the immediate relief that any of us who have suffered from mental illness can all relate to—the “shine a light” moment. That moment when we admit we are struggling while simultaneously taking a deep sigh of relief, knowing that we’ve identified the culprit—mental illness—and realizing that the enemy is exposed. There’s a physical response when we admit we are hurting—our shoulders relax, the tightness in our chest disappears, and it literally feels as if a weight has been lifted from our bodies. Think of it like a pressure valve or a cork in a bottle of champagne. All the pressure continues to build and build and build, and the moment that cork goes pop!, we feel an immediate relief of the pressure. Everything bubbles out and—if you’ve got a good bottle—life tastes really, really good in those first, fresh moments after you’ve opened the bottle.

I think we feel the most relief in those moments immediately after we shed the mask of shame and honestly talk about our fears, insecurities, and feelings. But for many who suffer and especially my Dad, as time wears on, we tend to slowly but surely put that mask back on. Over time, when we aren’t making our mental health a priority, we fall back into the old, comfortable patterns that led us down the wrong road in the first place. The less we talk about how we feel, the less light we shine on the enemy—and the less light we shine on the enemy, the more powerful it grows. And then, before we know it, the goodness that we felt in those immediate moments of relief completely retreats into the shadows. There we are again, stuck in the same place of guilt and inexplicable darkness that we were in before. The mask becomes comfortable again and seems to be a better alternative to being vulnerable.

Dear readers, I lost my Dad to suicide because of this, and I can promise you, there is nothing comfortable about not talking about our fears and feelings. It is a dead-end road, and one we must not pursue.

That’s why we have to talk, and we have to talk regularly. Yes, we must talk in the midst of our illness and in the immediate aftermath, but we also need to keep that conversation going as we begin to feel better, and yes, as we may begin to feel worse. We need to make vulnerability an everyday practice that’s as regular and accepted as brushing our teeth, washing our hands, or combing our hair. I confidently believe that so many of our real problems associated with mental illness are amplified and worsened when we don’t discuss them with others. I wish my Dad had felt comfortable enough to do more of that—and I wish that you would do more of it, too.

If you’re reading this post and you find yourself suffering from mental illness or suicidal ideations, I know that it can feel daunting and inescapable—but I promise you that the power mental illness holds over your life will dissipate when you shine a light on it and when you talk. You don’t have to talk to everyone. You don’t have to broadcast it on social media or in front of a crowd of thousands. But talk to someone, anyone. Shine a light by finding the people you trust most in your life and sharing your fear and worries with them. You’ll be shocked at how good it feels to shine the light on your mental illness—how good it feels to relieve the pressure, pop the cork, and let the feelings bubble out. And you’ll be amazed at how quickly the grip of mental illness is loosened.

It is no secret that, as I write this post, we are living in scary, confusing, fear-laden, and intensely unpredictable times. Unfortunately, the COVID-19 outbreak has taken a society that was already smoldering with fear and poured gasoline on that fire. If we were fearful a month ago, it’s likely that those feelings have grown much, much worse in the past days as we scramble to understand what is happening across the globe. As I pray for those who are hurting, there has been a heavy weight on my heart recently. It’s a heavy weight for those who are hurting and suffering from mental illness. It’s a worry that the mental illness they suffer from will grow even more powerful because of the unintentional effects of our needed physical isolation. Everyone is hurting, but those who suffer from mental illness may feel even less in control of their lives than they normally do.

In my heart of hearts, I’m convinced that there will be good that comes from this crisis. No, I don’t want it to happen, but yes, I believe that the Gospel is meant to invade dark places. Yes, there has been so much good happening in the midst of this difficult chapter. Individuals are more cognizant of the impact of their actions upon their communities and the world. Moments of generosity, I believe, are more abundant than they were previously. Without the convenience of a meal at a restaurant, a workout at the gym, or a movie with friends, I believe we’ve all grown to appreciate the little things that, for so long, we’ve taken for granted. Maybe we all needed a bit of a reminder that, above all and even with its many difficulties, life is grand and beautiful, complex yet lovingly simple.

At the same time, however, our worst fears and our primal instincts for self-preservation have amplified in ways we never imagined. Although outnumbered by the good, I don’t think I’ll ever be able to shake the image of two grown adults in a fisticuffs over a pack of Charmin at a Walmart as long as I live. When I go to the grocery store, I see the panic in people’s eyes that, when the world is right, just shouldn’t be there—and, unfortunately, I’ve felt it in my own heart. And I can’t help but think that, as much fear as we are seeing exhibited outwardly by so many people, the fear that people aren’t exhibiting is even worse, even greater, and even more destructive if it ever bubbles to the surface.

So if you are hurting or struggling from mental illness that you can’t explain, I beg you to not let these times of isolation prevent you from talking with someone. Find that trusted loved one or friend, call them, and just ask them if you can share your heart. Talk with them about your fears. Not everyone will be receptive, but I promise you that someone will. More than ever before, reach out to a counselor, therapist, or psychiatrist who can help bring those feelings to the surface in a way that is redemptive. And if the thought of suicide has crossed your mind, I beg you to call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 1-800-273-8255 or 1-800-273-TALK. Never, never let those thoughts linger. Never underestimate their power. Do something, in this moment, that will protect you, your families, and the generations to come. The world is better because you’re in it—promise me you’ll be here.

So if you are hurting or struggling from mental illness that you can’t explain, I beg you to not let these times of isolation prevent you from talking with someone. Find that trusted loved one or friend, call them, and just ask them if you can share your heart. Talk with them about your fears. Not everyone will be receptive, but I promise you that someone will. More than ever before, reach out to a counselor, therapist, or psychiatrist who can help bring those feelings to the surface in a way that is redemptive. And if the thought of suicide has crossed your mind, I beg you to call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 1-800-273-8255 or 1-800-273-TALK. Never, never let those thoughts linger. Never underestimate their power. Do something, in this moment, that will protect you, your families, and the generations to come. The world is better because you’re in it—promise me you’ll be here.

And lastly, for those fellow believers, I beg you to talk with God. Yes, He knows all, but there is great power in shining a light on our biggest fears and concerns and letting God know that we need help. Reveal the depths of your heart to the One who can reach down, provide solace, and restore peace. And find comfort in talking with him regularly because, the more we talk, the more comfortable and easy it becomes to be vulnerable—which, after all, is how God created us to be.

Together, we can create a culture of light-shiners who refuse to let our hurts grow and gain power in the dark. Now, more than ever, it’s time for all of us to start shining a light.

And please, dear neighbors, pick up your pizza boxes. Poor Penny and I can’t take it any longer.

Dad, My heart hurts deeply when I think about how fearful you likely felt throughout your life. It breaks my heart to know that you experienced such shame which prevented you from reaching out and talking to those of us who loved you. Dad, I just want you to know that we were never, ever disappointed in you. No matter how sick you might have been, and even during the times when your mental illness led you to leave us, we were never disappointed in the man you were. And now, I hope you are resting in the peace of Heaven and allowing God to remind you, daily, that He was never disappointed either. Your life continues to guide me and remind me of the importance of sharing my feelings with others, and although I don’t always do it perfectly, I’m grateful that you’re still parenting me and teaching me daily. I carry you with me every single day, Dad. Thank you, Dad, for showing courage in all those moments that matter most. I can’t wait to tell you, face to face, how proud I am of you for fighting the way you did. Until that glorious reunion, seeya Bub.

Dad, My heart hurts deeply when I think about how fearful you likely felt throughout your life. It breaks my heart to know that you experienced such shame which prevented you from reaching out and talking to those of us who loved you. Dad, I just want you to know that we were never, ever disappointed in you. No matter how sick you might have been, and even during the times when your mental illness led you to leave us, we were never disappointed in the man you were. And now, I hope you are resting in the peace of Heaven and allowing God to remind you, daily, that He was never disappointed either. Your life continues to guide me and remind me of the importance of sharing my feelings with others, and although I don’t always do it perfectly, I’m grateful that you’re still parenting me and teaching me daily. I carry you with me every single day, Dad. Thank you, Dad, for showing courage in all those moments that matter most. I can’t wait to tell you, face to face, how proud I am of you for fighting the way you did. Until that glorious reunion, seeya Bub.

“Help carry each other’s burdens. In this way you will follow Christ’s teachings.” Galatians 6:2 (GW)

Dad, At times, Christmas has felt so empty without you. My heart has been enraptured with pain when I think about what was stolen from you and us by mental illness. You deserved many more Christmases. You deserved to celebrate with our growing family, and to eventually be a Grandfather who were spoiled with your generosity and sense of childlike wonder. The holidays had a special sparkle when you were here to celebrate them, and since you’ve been gone, we’ve all felt an overwhelming sense of loss, guilt, and sadness. But the gift that was given to us was the reassuring truth of knowing that you are safe in God’s arms—free of pain, distress, and all the unfair difficulties that haunted you in this life. Dad, there is no question in my mind where your Eternal mailing address is. I know you are in Heaven, watching down over all of us and telling us that life is going to work out even on the days when the pain of losing you makes it hard to believe. I think of you all the time, but even more so on Christmas. Christmas was a happy time because you provided so much joy to those you loved. Watching the way you enjoyed spending time with your family has been an inspiration to me, and I wish you and I could sit around, share a glass of punch, and laugh again the way we always did. Dad, thank you for teaching me what it means to be a man who loves his family not just at Christmas, but every day of the year. I have many more Christmases to go without you, but I’m looking forward to that first one we can spend together in Eternity. Until that day, I love you. Merry Christmas, Bub.

Dad, At times, Christmas has felt so empty without you. My heart has been enraptured with pain when I think about what was stolen from you and us by mental illness. You deserved many more Christmases. You deserved to celebrate with our growing family, and to eventually be a Grandfather who were spoiled with your generosity and sense of childlike wonder. The holidays had a special sparkle when you were here to celebrate them, and since you’ve been gone, we’ve all felt an overwhelming sense of loss, guilt, and sadness. But the gift that was given to us was the reassuring truth of knowing that you are safe in God’s arms—free of pain, distress, and all the unfair difficulties that haunted you in this life. Dad, there is no question in my mind where your Eternal mailing address is. I know you are in Heaven, watching down over all of us and telling us that life is going to work out even on the days when the pain of losing you makes it hard to believe. I think of you all the time, but even more so on Christmas. Christmas was a happy time because you provided so much joy to those you loved. Watching the way you enjoyed spending time with your family has been an inspiration to me, and I wish you and I could sit around, share a glass of punch, and laugh again the way we always did. Dad, thank you for teaching me what it means to be a man who loves his family not just at Christmas, but every day of the year. I have many more Christmases to go without you, but I’m looking forward to that first one we can spend together in Eternity. Until that day, I love you. Merry Christmas, Bub.

Dad, For so long, I’ve tried to understand the level of despair you were feeling in the moment that your life ended. For the longest time, I wasn’t able to empathize with your pain. But individuals like Kathy have come into my life since losing you and have helped me gain that level of empathy. Dad, I am so sorry that you were hurting for so long. I’m so sorry that I wasn’t more forgiving in the times when you were hurting. I wish we had been able to help you find the healing that you needed and that you deserved. Dad, you had so much more to accomplish in this life. You had so many talents to contribute, and so many people left to love. I don’t know that I’ll ever understand how someone with such an unbelievable level of kindness, skill, and grace could feel as helpless as you did. But Dad, I promise to you that you will never be defined by your death. I will do everything I can to make sure that people remember you for the vivid life you lived, and I’ll make sure that your death (like Kathy’s story) gives people a hopeful reminder that life is worth living. Dad, thank you for equipping me with the courage to face life head-on in the aftermath of your death. It’s amazing to think that you were always teaching me the skills I would eventually need to deal with life after you. I’ll never stop learning from you, and I can’t wait to thank you for always giving me that inspiration. Until the day when I see your face again, seeya Bub.

Dad, For so long, I’ve tried to understand the level of despair you were feeling in the moment that your life ended. For the longest time, I wasn’t able to empathize with your pain. But individuals like Kathy have come into my life since losing you and have helped me gain that level of empathy. Dad, I am so sorry that you were hurting for so long. I’m so sorry that I wasn’t more forgiving in the times when you were hurting. I wish we had been able to help you find the healing that you needed and that you deserved. Dad, you had so much more to accomplish in this life. You had so many talents to contribute, and so many people left to love. I don’t know that I’ll ever understand how someone with such an unbelievable level of kindness, skill, and grace could feel as helpless as you did. But Dad, I promise to you that you will never be defined by your death. I will do everything I can to make sure that people remember you for the vivid life you lived, and I’ll make sure that your death (like Kathy’s story) gives people a hopeful reminder that life is worth living. Dad, thank you for equipping me with the courage to face life head-on in the aftermath of your death. It’s amazing to think that you were always teaching me the skills I would eventually need to deal with life after you. I’ll never stop learning from you, and I can’t wait to thank you for always giving me that inspiration. Until the day when I see your face again, seeya Bub.  Kathy Dolch

Kathy Dolch

Dad, You lived a big and vibrant life while you were here with all of us, and your absence is even more noticeable and painful because the void left behind is so great. You deserved to live a fuller life than the one you experienced, and I’m sorry I didn’t do more to make that dream reality. Dad, I would have loved watching you grow old—even though it might not have been as much fun for you as it would have been for me. I would have loved seeing you on my wedding day, and you have no idea how much I would have appreciated your wisdom about navigating this new chapter in my life because you were such an amazing husband for Mom. And yes, I would have loved watching you become a grandpa more than anything else. I know you would have been silly and goofy and ridiculous—and completely adored by your grandchildren. But Dad, as much as I wanted to watch those things for myself, I’m ultimately saddened because you earned the right to experience all of those wonderful things. I hate mental illness and suicide for robbing you of these life chapters. Mental illness separated you from us and from many wonderful, beautiful moments that awaited your future. And although I won’t get to watch you enjoy life, and although I’ll always have questions about why this happened to you, I do find peace knowing that you’re not suffering any longer. I find a sense of comfort knowing that the unjustified feelings of shame and embarrassment that you experienced in this world are completely gone and fully redeemed. And I know that as great as any experience you could have had here with us might have been, you’re experiencing a joy and beauty beyond any other as you bask in the glory of Heaven and God’s everlasting love and paradise. Dad, keep watching over me, and keep reassuring me that you were called Home for a reason. I love you, and I wish we could have experienced more of this life together; but I know there’s a greater reward and an unbelievable reunion awaiting us. Thank you Dad, and until the day when we are reunited forever, seeya Bub.

Dad, You lived a big and vibrant life while you were here with all of us, and your absence is even more noticeable and painful because the void left behind is so great. You deserved to live a fuller life than the one you experienced, and I’m sorry I didn’t do more to make that dream reality. Dad, I would have loved watching you grow old—even though it might not have been as much fun for you as it would have been for me. I would have loved seeing you on my wedding day, and you have no idea how much I would have appreciated your wisdom about navigating this new chapter in my life because you were such an amazing husband for Mom. And yes, I would have loved watching you become a grandpa more than anything else. I know you would have been silly and goofy and ridiculous—and completely adored by your grandchildren. But Dad, as much as I wanted to watch those things for myself, I’m ultimately saddened because you earned the right to experience all of those wonderful things. I hate mental illness and suicide for robbing you of these life chapters. Mental illness separated you from us and from many wonderful, beautiful moments that awaited your future. And although I won’t get to watch you enjoy life, and although I’ll always have questions about why this happened to you, I do find peace knowing that you’re not suffering any longer. I find a sense of comfort knowing that the unjustified feelings of shame and embarrassment that you experienced in this world are completely gone and fully redeemed. And I know that as great as any experience you could have had here with us might have been, you’re experiencing a joy and beauty beyond any other as you bask in the glory of Heaven and God’s everlasting love and paradise. Dad, keep watching over me, and keep reassuring me that you were called Home for a reason. I love you, and I wish we could have experienced more of this life together; but I know there’s a greater reward and an unbelievable reunion awaiting us. Thank you Dad, and until the day when we are reunited forever, seeya Bub.

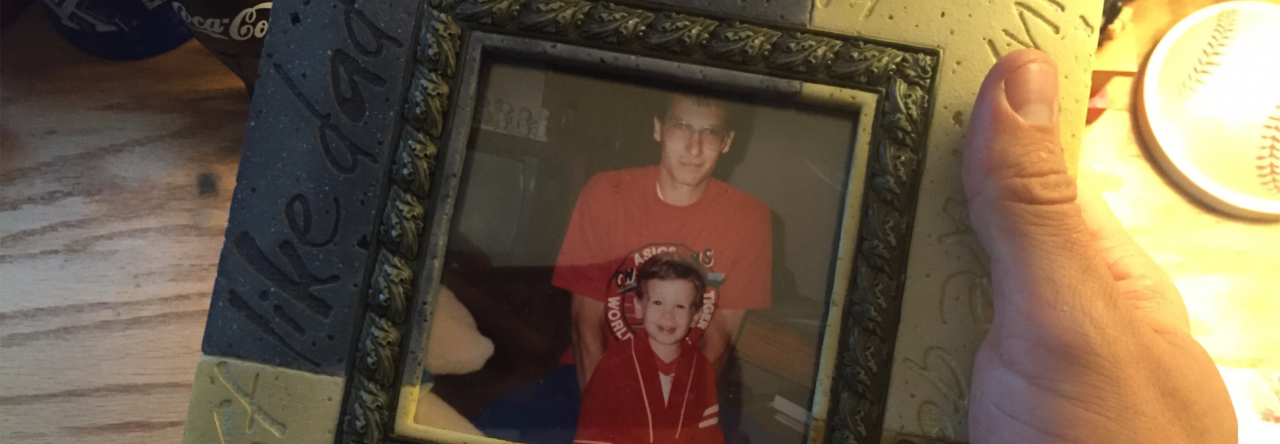

Dad, Of all the difficult things that have happened since losing you, watching other fathers and sons has likely been the hardest. I still get jealous when I see other fathers and sons enjoying life together, because deep down I feel that you and I were robbed of precious time spent with one another. I don’t always know how to deal with these feelings, but you taught me to appreciate what we have in life more than longing for what we don’t have. And for all the experiences and moments that we might not have been able to share with one another, the 26 years that we did spend together as Father and Son here on earth were always filled with life, adventure, appreciation, and love. You taught me that it’s okay to be hurt and to not know all of the answers, but that in spite of that hurt, we should strive to love others at all times. And Dad, in spite of the pain I still feel to this day, I often ask God to teach me how to love others like you did. Although I still experience jealousy, it’s always coupled with an unfailing sense of longing for what is to come—a heavenly reunion in which I’ll be able to tell you, again, how much I loved you. Thank you, Dad, for always modeling hope. Thank you for giving me indelible memories that will never, ever be erased by the pain of jealousy. And thank you for loving me and everyone in your life with gusto. I love you, Dad, and until we can enjoy the gift of being near one another again, seeya Bub.

Dad, Of all the difficult things that have happened since losing you, watching other fathers and sons has likely been the hardest. I still get jealous when I see other fathers and sons enjoying life together, because deep down I feel that you and I were robbed of precious time spent with one another. I don’t always know how to deal with these feelings, but you taught me to appreciate what we have in life more than longing for what we don’t have. And for all the experiences and moments that we might not have been able to share with one another, the 26 years that we did spend together as Father and Son here on earth were always filled with life, adventure, appreciation, and love. You taught me that it’s okay to be hurt and to not know all of the answers, but that in spite of that hurt, we should strive to love others at all times. And Dad, in spite of the pain I still feel to this day, I often ask God to teach me how to love others like you did. Although I still experience jealousy, it’s always coupled with an unfailing sense of longing for what is to come—a heavenly reunion in which I’ll be able to tell you, again, how much I loved you. Thank you, Dad, for always modeling hope. Thank you for giving me indelible memories that will never, ever be erased by the pain of jealousy. And thank you for loving me and everyone in your life with gusto. I love you, Dad, and until we can enjoy the gift of being near one another again, seeya Bub.

Dad, I’m sorry for all of those moments that we should have spent together. I’m sorry for all of those times that I wasted when we had the opportunity to just be together, but I didn’t realize the value of those moments. Ultimately, I’m just sorry we didn’t have more time. Dad, you brought such joy to my life—and to everyone’s life that you interacted with. Any amount of time with you would have failed to be enough. There are so many things we should have done together, and I’m sorry I didn’t make a more genuine effort to make those things happen. Dad, I hope that I’m still learning from your life. I hope that I am taking the time that God has given me and using it more wisely than I did before you died. It still doesn’t erase the pain of losing you and the desire to have more of you in my life, but I hope that I’m realizing the fragility of life and the need to invest my time in the things that matter—the things associated with loving God and loving other people. Dad, please continue teaching me. Thank you for living a vivid life that still feels important each and every day. And Dad, I’m keeping a list of all those things we should have done. Someday, we will have the opportunity to do them all, and I can’t wait. Until that day and the glorious reunion that awaits, seeya Bub.

Dad, I’m sorry for all of those moments that we should have spent together. I’m sorry for all of those times that I wasted when we had the opportunity to just be together, but I didn’t realize the value of those moments. Ultimately, I’m just sorry we didn’t have more time. Dad, you brought such joy to my life—and to everyone’s life that you interacted with. Any amount of time with you would have failed to be enough. There are so many things we should have done together, and I’m sorry I didn’t make a more genuine effort to make those things happen. Dad, I hope that I’m still learning from your life. I hope that I am taking the time that God has given me and using it more wisely than I did before you died. It still doesn’t erase the pain of losing you and the desire to have more of you in my life, but I hope that I’m realizing the fragility of life and the need to invest my time in the things that matter—the things associated with loving God and loving other people. Dad, please continue teaching me. Thank you for living a vivid life that still feels important each and every day. And Dad, I’m keeping a list of all those things we should have done. Someday, we will have the opportunity to do them all, and I can’t wait. Until that day and the glorious reunion that awaits, seeya Bub.

Dad, There are many moments when I think about your last day here on Earth and wish, desperately, that it would have ended differently. I can’t even begin to fathom or understand the pain and despair you must have felt in those moments. You loved life so much, which shows me how much hopelessness you were experiencing to believe that life wasn’t worth living any longer. I cry when I think of those moments because, Dad, you were so loved by so many. You should be here, right now, living life and loving every step along the way. You deserved that type of hope. But Dad, even in the midst of the pain you probably felt in those last few minutes, I’m grateful that you aren’t experiencing that pain any longer. You now reside in an everlasting paradise of joy, hope, comfort, and eternal fellowship with the God who loves you and loves all of us. Dad, I wake up every day wishing I could see you again. I picture your face and I can see your smile, and I just want you to be back here with us. But because you’re not, I’ll take comfort in the fact that I know where you are. And that I know I’ll see you again. I love you Dad. Until that wonderful reunion, seeya Bub.

Dad, There are many moments when I think about your last day here on Earth and wish, desperately, that it would have ended differently. I can’t even begin to fathom or understand the pain and despair you must have felt in those moments. You loved life so much, which shows me how much hopelessness you were experiencing to believe that life wasn’t worth living any longer. I cry when I think of those moments because, Dad, you were so loved by so many. You should be here, right now, living life and loving every step along the way. You deserved that type of hope. But Dad, even in the midst of the pain you probably felt in those last few minutes, I’m grateful that you aren’t experiencing that pain any longer. You now reside in an everlasting paradise of joy, hope, comfort, and eternal fellowship with the God who loves you and loves all of us. Dad, I wake up every day wishing I could see you again. I picture your face and I can see your smile, and I just want you to be back here with us. But because you’re not, I’ll take comfort in the fact that I know where you are. And that I know I’ll see you again. I love you Dad. Until that wonderful reunion, seeya Bub.  Reverend Dan Walters

Reverend Dan Walters

Every single day is difficult—all 1,827 of them; but every single year, July 24 is a date that stares at me from the calendar. It looms in the distance for months, and when it passes, I always breathe a sigh of relief that it’s come and gone. But I know, deep down, that it’s coming again. It will always be there. No particular July 24 has been more or less difficult—just different. But because of the nice, round number, this one feels like a milestone. A milestone I wish I didn’t have to reach.

Every single day is difficult—all 1,827 of them; but every single year, July 24 is a date that stares at me from the calendar. It looms in the distance for months, and when it passes, I always breathe a sigh of relief that it’s come and gone. But I know, deep down, that it’s coming again. It will always be there. No particular July 24 has been more or less difficult—just different. But because of the nice, round number, this one feels like a milestone. A milestone I wish I didn’t have to reach. But guess what? No amount of procrastination could stop that date from coming. No amount of denial could stop me from thinking about what this day represents. This day would come—and yes, it would eventually pass—but the second it did, the clock just begin counting down towards another unfortunate milestone. The next Christmas. The next birthday. The next Father’s Day.

But guess what? No amount of procrastination could stop that date from coming. No amount of denial could stop me from thinking about what this day represents. This day would come—and yes, it would eventually pass—but the second it did, the clock just begin counting down towards another unfortunate milestone. The next Christmas. The next birthday. The next Father’s Day. On the other side of all that grief and sadness, there will be an everlasting love made whole again. On the other side of that grief, there will be a man whom I recognize, smiling and welcoming me into his arms. In that moment, I’ll love never having to say “seeya, Bub” again. That day is coming, although it’s very far off.

On the other side of all that grief and sadness, there will be an everlasting love made whole again. On the other side of that grief, there will be a man whom I recognize, smiling and welcoming me into his arms. In that moment, I’ll love never having to say “seeya, Bub” again. That day is coming, although it’s very far off. Dad, I cry so much when I think that it’s been five years since you and I last talked. Sometimes, those tears are unstoppable. We never even went five days in this life without talking to one another. Dad, it really has felt like an eternity—but sometimes your memory is so real and so vivid that it seems like it was just yesterday when we lost you. But I know the real time. I know that it’s been five whole years since we’ve been able to be in your presence. And life simply isn’t the same without you. We all cling to your memory. We marvel at the things you built and the way you provided for our family. We laugh about the funny things you did to make life more fun. But I also weep when I think about how much life you had left to live. Dad, I’m so sorry that you were sick. I feel horrible that we couldn’t do more to help you find the cure you deserved. I’m sorry that you were robbed of the life you deserved to enjoy. I’ve felt so much guilt in losing you Dad. I know that you don’t want me to feel this way, but I just wish there was more I could have done. You deserved that, Dad. You deserved more, because you gave everything. As painful as these five years have been, Dad, I find peace in the truth of Eternity. I find comfort knowing that you are enjoying God’s eternal glory in a paradise that I can’t even begin to fathom. Dad, thank you for watching over me for these past five years. Thank you for never giving up on me—both in this life, and in the next. Thank you for giving me a lifetime of memories and an example of what fatherhood should be. I love you, Dad. I always did, and I always will. Thank you for loving me back. Until I see you again, seeya Bub.

Dad, I cry so much when I think that it’s been five years since you and I last talked. Sometimes, those tears are unstoppable. We never even went five days in this life without talking to one another. Dad, it really has felt like an eternity—but sometimes your memory is so real and so vivid that it seems like it was just yesterday when we lost you. But I know the real time. I know that it’s been five whole years since we’ve been able to be in your presence. And life simply isn’t the same without you. We all cling to your memory. We marvel at the things you built and the way you provided for our family. We laugh about the funny things you did to make life more fun. But I also weep when I think about how much life you had left to live. Dad, I’m so sorry that you were sick. I feel horrible that we couldn’t do more to help you find the cure you deserved. I’m sorry that you were robbed of the life you deserved to enjoy. I’ve felt so much guilt in losing you Dad. I know that you don’t want me to feel this way, but I just wish there was more I could have done. You deserved that, Dad. You deserved more, because you gave everything. As painful as these five years have been, Dad, I find peace in the truth of Eternity. I find comfort knowing that you are enjoying God’s eternal glory in a paradise that I can’t even begin to fathom. Dad, thank you for watching over me for these past five years. Thank you for never giving up on me—both in this life, and in the next. Thank you for giving me a lifetime of memories and an example of what fatherhood should be. I love you, Dad. I always did, and I always will. Thank you for loving me back. Until I see you again, seeya Bub.

Dad, There have been so many times when I’ve thought about the fear you must have experienced in your life. You were always my Superman—that strong rock and foundation in my life when everything else seemed dangerous. On the outside, you were always “Mr. Fix It,” and I know it bothered you that you couldn’t solve your own struggles with depression. On the surface, you always held everything together—for your family, for your friends, and especially for Mom and I. But Dad, I wish I could have told you that your struggles with mental illness were never a disappointment to any of us. We never thought less of you when you battled with your depression. Sick or healthy, we always loved you and wanted to be near you. You were never a failure to us, Dad. You never failed us, and I wish you had known that more. I am afraid of doing life without you. I have a fear that I can’t do what God is calling me to do to tell your story. But I know that He is with me, and I know that you are with me. I know that you are watching down and pushing me and urging me onward, just as you always did when you were here with us. We all miss you, Dad. We will never stop missing you. You never let me down, and I can’t wait to tell you that in person. Until that day, seeya Bub.

Dad, There have been so many times when I’ve thought about the fear you must have experienced in your life. You were always my Superman—that strong rock and foundation in my life when everything else seemed dangerous. On the outside, you were always “Mr. Fix It,” and I know it bothered you that you couldn’t solve your own struggles with depression. On the surface, you always held everything together—for your family, for your friends, and especially for Mom and I. But Dad, I wish I could have told you that your struggles with mental illness were never a disappointment to any of us. We never thought less of you when you battled with your depression. Sick or healthy, we always loved you and wanted to be near you. You were never a failure to us, Dad. You never failed us, and I wish you had known that more. I am afraid of doing life without you. I have a fear that I can’t do what God is calling me to do to tell your story. But I know that He is with me, and I know that you are with me. I know that you are watching down and pushing me and urging me onward, just as you always did when you were here with us. We all miss you, Dad. We will never stop missing you. You never let me down, and I can’t wait to tell you that in person. Until that day, seeya Bub. Reverend Dan Walters

Reverend Dan Walters

When I was extremely young, my family never took beach vacations. To this day, I’m not sure why because we all loved the beach so much. My very first time seeing the ocean was on a family trip to Panama City, Florida as an eighth grader. Our entire family (grandparents and cousins included) spent a wonderful week on the Gulf Coast, and I remember the momentous nature of that trip, even as a middle schooler. A 12-hour, multi-day car ride had finally concluded, and my Mom and Dad walked me out towards the ocean once we arrived. With my parents, I saw the ocean for the very first time and I got to experience its magnitude. I got to touch sand, and taste saltwater, and splash in the world’s largest pool. Even as a young kid, I appreciated the significance of this experience.

When I was extremely young, my family never took beach vacations. To this day, I’m not sure why because we all loved the beach so much. My very first time seeing the ocean was on a family trip to Panama City, Florida as an eighth grader. Our entire family (grandparents and cousins included) spent a wonderful week on the Gulf Coast, and I remember the momentous nature of that trip, even as a middle schooler. A 12-hour, multi-day car ride had finally concluded, and my Mom and Dad walked me out towards the ocean once we arrived. With my parents, I saw the ocean for the very first time and I got to experience its magnitude. I got to touch sand, and taste saltwater, and splash in the world’s largest pool. Even as a young kid, I appreciated the significance of this experience. After a really, really long drive, my family finally arrived to our condo in Gulf Shores. Shortly after arriving, I think we all knew then that we had found our family vacation spot. There was something about it that made us feel like we were home.

After a really, really long drive, my family finally arrived to our condo in Gulf Shores. Shortly after arriving, I think we all knew then that we had found our family vacation spot. There was something about it that made us feel like we were home. As I’ve written before, Dad was a tremendous athlete. And also as I’ve written before, I was a horrible one. But Dad never let my lack of athleticism curb an opportunity to play. At the beach, Dad and I could throw a frisbee for hours—as long as the wind cooperated. We would warm up close to one another and gradually step back as we threw until we would finally hit a point where we had to wind our torsos like a corkscrew to get the frisbee to sail over the white sand. Dad and I would leap and dive into the sand to catch a frisbee—his leaps and dives always significantly more graceful than mine—and we would yell at each other for not being able to properly hit our target. “Did you actually expect me to catch that?!” we would yell across the beach at one another. “You’re gonna kill a kid with that thing if you don’t learn how to throw it!”

As I’ve written before, Dad was a tremendous athlete. And also as I’ve written before, I was a horrible one. But Dad never let my lack of athleticism curb an opportunity to play. At the beach, Dad and I could throw a frisbee for hours—as long as the wind cooperated. We would warm up close to one another and gradually step back as we threw until we would finally hit a point where we had to wind our torsos like a corkscrew to get the frisbee to sail over the white sand. Dad and I would leap and dive into the sand to catch a frisbee—his leaps and dives always significantly more graceful than mine—and we would yell at each other for not being able to properly hit our target. “Did you actually expect me to catch that?!” we would yell across the beach at one another. “You’re gonna kill a kid with that thing if you don’t learn how to throw it!” And at the beach, Dad never played it safe. More than anything, I think Dad and I probably got the most enjoyment of our daily game of “See Who Can Swim the Furthest Out from the Shore and Make Mom Freak Out the Most” (catchy, no?). Much to my Mom’s displeasure, Dad and I were notorious for jumping into the water and swimming straight ahead until our arms gave out. The water would grow colder and colder the further we would swim, and periodically Dad would stick his arms high above his head and straight-dive down to see if he could still touch the bottom. If he could, we still weren’t out far enough. All the while, my poor Mother would sit anxiously in her beach chair watching our bobbing heads grow smaller and smaller in the waves. The best version of the game was on the beaches where there were life guards on duty, and in those scenarios, we tried to see how loud we could get them to blow their whistles at us! We knew we were really killing the game if we could swim far enough to encounter a deeper sandbar, and if we did, we would sit out on the sandbar and rest until it was time to swim back in. Dad would wave to Mom on occasion from the depths of the mighty ocean, and it was amazing how peaceful the deep ocean water can be. All the ambient noises of the beach fade away when you’re that far out (you especially can’t hear life guard whistles or motherly-shrieks).

And at the beach, Dad never played it safe. More than anything, I think Dad and I probably got the most enjoyment of our daily game of “See Who Can Swim the Furthest Out from the Shore and Make Mom Freak Out the Most” (catchy, no?). Much to my Mom’s displeasure, Dad and I were notorious for jumping into the water and swimming straight ahead until our arms gave out. The water would grow colder and colder the further we would swim, and periodically Dad would stick his arms high above his head and straight-dive down to see if he could still touch the bottom. If he could, we still weren’t out far enough. All the while, my poor Mother would sit anxiously in her beach chair watching our bobbing heads grow smaller and smaller in the waves. The best version of the game was on the beaches where there were life guards on duty, and in those scenarios, we tried to see how loud we could get them to blow their whistles at us! We knew we were really killing the game if we could swim far enough to encounter a deeper sandbar, and if we did, we would sit out on the sandbar and rest until it was time to swim back in. Dad would wave to Mom on occasion from the depths of the mighty ocean, and it was amazing how peaceful the deep ocean water can be. All the ambient noises of the beach fade away when you’re that far out (you especially can’t hear life guard whistles or motherly-shrieks). My Grandpa even told a story at Dad’s funeral about his love for always being the last one up. On occasion, my family would take vacations with our extended family, which included my Grandpa Vern, Grandma Sharon, my Uncle Lee, my Aunt Beth, and my two cousins Jake and Megan. Those were always wonderful vacations, and every day, my Grandpa and my Dad were always the last ones up to the condo. But even my Grandpa couldn’t hang with my Dad.

My Grandpa even told a story at Dad’s funeral about his love for always being the last one up. On occasion, my family would take vacations with our extended family, which included my Grandpa Vern, Grandma Sharon, my Uncle Lee, my Aunt Beth, and my two cousins Jake and Megan. Those were always wonderful vacations, and every day, my Grandpa and my Dad were always the last ones up to the condo. But even my Grandpa couldn’t hang with my Dad. Standing there at the beach, I told Steve how much I missed my Dad. I really didn’t have to say anything, because Steve knew—and he was experiencing the grief himself. Steve had been tremendously close with my entire family, and my Dad treated him just like he would treat his own son. Instead of only crying, though, I was able to share tremendous memories and stories of my Dad, telling Steve all about the funny things he had done at the beach on our family vacations. I shared stories about Dad’s Banana Boat expedition, his wave-runner sandbar collision, and how he was always the last one up for dinner. Little by little, the tears were slowly replaced with a smile and laughter. I didn’t miss him any less; I just had a different focus. Instead of focusing on the loss, I was able to focus on his life. Instead of focusing on the time we didn’t have together, I focused on all the wonderful times we did.

Standing there at the beach, I told Steve how much I missed my Dad. I really didn’t have to say anything, because Steve knew—and he was experiencing the grief himself. Steve had been tremendously close with my entire family, and my Dad treated him just like he would treat his own son. Instead of only crying, though, I was able to share tremendous memories and stories of my Dad, telling Steve all about the funny things he had done at the beach on our family vacations. I shared stories about Dad’s Banana Boat expedition, his wave-runner sandbar collision, and how he was always the last one up for dinner. Little by little, the tears were slowly replaced with a smile and laughter. I didn’t miss him any less; I just had a different focus. Instead of focusing on the loss, I was able to focus on his life. Instead of focusing on the time we didn’t have together, I focused on all the wonderful times we did. I spend a lot of time on the beach during dusk as many of the families on the shore will begin to retreat to their condos. And I do this for a simple reason: that’s what Dad would have done. I’ve learned why he loved it so much. As the beach starts to quiet down from a busy day of frivolity and fun, there’s a quiet stillness that begins to wash across the shore. That stillness is enticing and comforting, and it’s in those moments that I often feel closest to God. And I think about how peaceful those moments must have been to a man who struggled with depression. Dad treasured that peace. And now, I treasure the memory of his life during those peaceful moments, and I try to live it out every chance I get.

I spend a lot of time on the beach during dusk as many of the families on the shore will begin to retreat to their condos. And I do this for a simple reason: that’s what Dad would have done. I’ve learned why he loved it so much. As the beach starts to quiet down from a busy day of frivolity and fun, there’s a quiet stillness that begins to wash across the shore. That stillness is enticing and comforting, and it’s in those moments that I often feel closest to God. And I think about how peaceful those moments must have been to a man who struggled with depression. Dad treasured that peace. And now, I treasure the memory of his life during those peaceful moments, and I try to live it out every chance I get. Dad, there has never been a time when I’ve gone to the beach without thinking of you—and there never will be. You made our time at the beach together so memorable, but more than that, you taught me so many important life lessons while we were there. You taught me to slow down and relax. You taught me to soak in God’s beautiful creation. You taught me to be kind to people and get to know them, because God created them, too. You taught me to let go of all the busy things from back home and simply enjoy the life that was in front of me in that moment. I take these lessons with me everywhere I go, but especially when I go to the beach. Even though I’m still able to have fun when I go, it just isn’t the same without you. I miss our throwing sessions, and sometimes I’ll just carry a baseball in my backpack to turn over and over in my hands and think of the time we spent together. I miss trying to see who could swim the furthest out, and watching you beckon me further even when I felt like I couldn’t keep swimming. I miss walking along the shoreline with you and listening to your stories about oil rigs in the distance or planes flying overhead. You had an inquisitive, appreciative spirit for all life had to offer. And more than anything, I miss watching you enjoy those moments on the shore by yourself being the last one up. It’s strange, but sometimes it’s like I look down from the balcony and I can still see you sitting there. Dad, I know you’re still with me. I know that you’re guiding me and watching over me in everything that I do. Thank you for always being my best teacher. Thank you for being a Dad unlike any other. And thank you for always teaching me that the last one up wins. I love you, Dad. I miss you tremendously. I sure hope there are beaches in heaven, because if there are, I promise I’m going to swim further out than you. Until that day when we can be beachside together again, seeya Bub.

Dad, there has never been a time when I’ve gone to the beach without thinking of you—and there never will be. You made our time at the beach together so memorable, but more than that, you taught me so many important life lessons while we were there. You taught me to slow down and relax. You taught me to soak in God’s beautiful creation. You taught me to be kind to people and get to know them, because God created them, too. You taught me to let go of all the busy things from back home and simply enjoy the life that was in front of me in that moment. I take these lessons with me everywhere I go, but especially when I go to the beach. Even though I’m still able to have fun when I go, it just isn’t the same without you. I miss our throwing sessions, and sometimes I’ll just carry a baseball in my backpack to turn over and over in my hands and think of the time we spent together. I miss trying to see who could swim the furthest out, and watching you beckon me further even when I felt like I couldn’t keep swimming. I miss walking along the shoreline with you and listening to your stories about oil rigs in the distance or planes flying overhead. You had an inquisitive, appreciative spirit for all life had to offer. And more than anything, I miss watching you enjoy those moments on the shore by yourself being the last one up. It’s strange, but sometimes it’s like I look down from the balcony and I can still see you sitting there. Dad, I know you’re still with me. I know that you’re guiding me and watching over me in everything that I do. Thank you for always being my best teacher. Thank you for being a Dad unlike any other. And thank you for always teaching me that the last one up wins. I love you, Dad. I miss you tremendously. I sure hope there are beaches in heaven, because if there are, I promise I’m going to swim further out than you. Until that day when we can be beachside together again, seeya Bub.