My Dad loved riding a bike. I loved it too—but I did not love the crashing part.

When we moved to our house on Headgates Road, I started noticing my Dad’s interest in biking. Always the one to buy the most tricked-out, high-tech equipment associated with anything he did, my Dad went out and bought a 21-speed mountain bike shortly after we moved into the neighborhood. Before long, he would affix a headlight and a speedometer to the bike, upgrade the seat, and buy tires that would allow him to bike through the deepest of snow, the muddiest mud, or the gravelliest gravel.

The Headgates Road neighborhood really is a biker’s paradise—even more so now than it was when we first moved in. There was minimal traffic throughout the neighborhood, and it offered a ton of side streets and cul-de-sacs that were free of everything but the local traffic. The neighborhood was always pretty well-lit, and as more and more people desired to move to that part of town, the development of new homes brought with it more streets and sidewalks for my Dad to ride on. Our neighborhood was also perfectly located adjacent to Rentschler Park, a forest-like preserve with plenty of hiking and biking trails. Eventually, an expansion of the neighborhood connected our home to the park via a service road, and now, it’s even more grand. Many folks take advantage of the new bike path that connects Rentschler Park in Hamilton/Fairfield Township to Waterworks Park in Fairfield—a path that winds for about 12 miles along the Great Miami River.

Even before all of the paths were added in, though, Dad was a biker at heart. Oftentimes, that was how he relaxed after dinner. He would scarf down a delicious meal cooked by Mom, guzzle down a can of Coca-Cola (or two), and then hop on his bike for an evening ride as the sun would set.

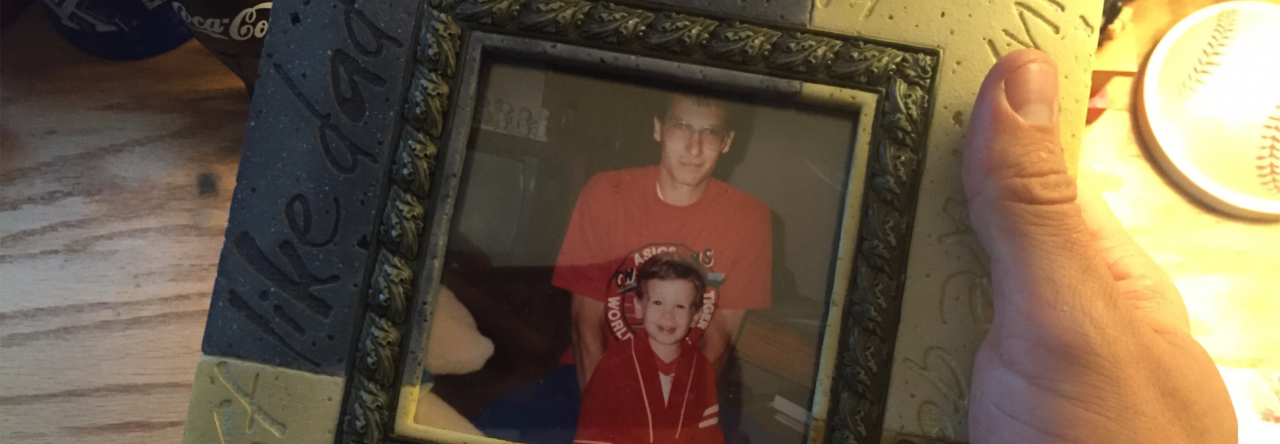

Dad was always willing to have me—his “little buddy”—along for the ride. From the time I was little, I always had a bike, and Dad always encouraged me to ride it. I remember how happy he was when I ditched the training wheels, and how he always threw caution to the wind and encouraged me to be adventurous. He was that Dad who always encouraged me to pedal faster, pop a wheelie, or jump on a ramp, even though that call to “go wild” never really sunk in. I was always a pretty cautious little biker. I enjoyed it, but I also appreciated the bones in both my arms and legs and didn’t want to do anything to put their operational ability in peril.

On those nights when I did join Dad for a bike ride, he was always patient. He always waited for me to catch up to him. He never treated me like I was a nuisance or annoyance, even though in hindsight I can see that I probably was. If I went on a ride with Dad, it actually worked out for him because he ended up getting two rides in that night. After dropping me off at the house to grab a post-pedal-popsicle, he would hop back on the saddle and cruise out again for a few more miles in the setting sun.

Dad loved everything about a bike ride. He loved the exercise. He loved the rhythm. He loved the wind in his hair; and then, when his hair was gone, he loved the wind on his scalp. He loved spending time in nature, and a bike allowed him to cover more ground and appreciate even more of it. Of all the times that I saw my Dad on a bike, I don’t think I ever saw him without a smile.

Except for that time when I went over the handlebars.

Have you ever flipped over the handlebars of a bike? It sounds more fun than it is. I mean, I guess the element of flight is fun; it’s the crashing part that’s brutal. Usually there’s some kind of painful cracking or bruising or loss of fluids that doesn’t sound like my idea of a good time. But it’s the risk you take when you ride a bike, and if you’re as uncoordinated as me, it’s a risk that comes with pretty bad odds.

My Dad was always the parent leader when it came to bike rides with all of my neighborhood friends, and there were many times that Dad would effortlessly lead a group of seven or eight grade schoolers—all with different biking skill and capability—on a trail ride through the hills at Rentschler Park. There were a number of different neighborhood playmates that I biked with: Devin, Brittany, her brother Jeremy, brothers Matt and Ryan (or “Peanut” as we always called him), and Anthony and Greg (otherwise known as “The Twins). It was funny that my Dad was often the adventurous “leader of the bike pack” considering that I was the absolute least adventurous kid on that list. All of my friends were much more risk-attuned than I was, and I think that’s why my Dad liked hanging out with them and liked that I was around them as well. Deep down, he had to secretly hope that some of their no-fear-nature would rub off on me.

As a kid, Dad always made these bike rides so fun and so enjoyable. Like he did at any family gathering, vacation bible school playtime, or church softball game, my Dad was a consummate entertainer. He was always on board for whatever silliness it took to propel my little legs on that bike. If it meant he had to pretend that he was a villain and I was the good guy chasing him, he’d do it. Or if he had to pretend that he was a rabid wolf that had somehow learned how to ride a bike and give me a 20-second headstart to get away as he foamed at the mouth and snarled, he’d do it. Dad loved having fun, he loved being outdoors, and he loved making people laugh—and taking me and all the neighborhood kids on a bike ride was pure joy for him.

Dad would often take us on a bicycle caravan through the infamous “Pinecone Trail” at Rentschler Park, a beautiful mile-and-a-half-or-so trail that includes hills, bridges, stairs, and narrow pathways that wind through tall trees along a stunning creek bed filled with rocks and calmly cascading water.

There’s not a caution sign to be had on that trail, and Dad absolutely loved it.

I don’t know how he did it, but Dad would ride that entire trail without getting off his bike seat once. He would pump his pedals up steeply-graded hills. He would whip through hairpin turns nearly skidding into tree stumps. And staircases? He didn’t even get off his bike at staircases!!! He’d either skirt the staircase and ride down the hill to the left of the stairs, or in a dangerous “kids, don’t try this at home” fashion, he’d just find a way to ride down the staircase on the bike.

It’s a good thing I didn’t have a daredevil spirit as a kid, because my Dad would have been a really bad influence on bike rides.

It didn’t stop him from trying though. Deep down, although he never would have admitted it, I think my Dad always wished I had a bit more of a rebellious streak in me. I think that my Dad wanted me to not be so cautious, to get a few more bumps, knicks, scrapes, and bruises. I know that my Dad loved me, but I also think that he often wondered how his only offspring could have ended up being so timid. Dad would goad me on during most of those bike rides, as I was inevitably the kid at the back of the line slowing down the entire chain of young peddlers and praying to my God and any others who would listen for a juice break. “Come on Bub,” he’d yell. “We gotta get home before it gets dark….heck, at the rate you’re going, we gotta get home before the sun comes up again!”

Every now and then, I’d get frustrated with Dad for pushing me to be a bit more adventurous when we rode bikes. I’d yell back at him and tell him that there was no way I could possibly pedal any further, and then tell him to just leave me for dead (did I mention that I had a flare for the dramatics as a kid?). Dad would bid me adieu and tell me to say hello to the coyotes that came out at night, and I’d pick up and pedal frantically to catch up to him.

But every now and then, the adventurous streak would flare up. It wasn’t much of a streak, but a streak nonetheless.

I don’t remember how old I was on this particular trip, but Dad had taken my friends and I out for a bike ride through the woods, and we were making our way home. The paths had been cleared and redirected as a result of some new housing developments in the area, and to Dad’s glee, the woods had been cleared to provide a new exit from Rentschler Park that involved speeding down a long, sloping hill, coming up another hill, and then flying down a much steeper hill on the other side to link up the newly-paved bike path.

It was a daredevil’s perfect ending to a long bike ride.

And I almost peed my pants just looking at it.

Per usual, Dad went first, hooting and hollering the entire way. My more adventurous friends followed, and before I knew it, I was the only kid at the top of the hill. I could feel the cold sweat forming across my body, and for a momentary second, I flirted with the idea of pretending to faint and collapse. However, I was afraid there might be snakes in the grass, so I ditched that plan quickly.

“Come on, Bub! It’s fun—you’re gonna love it!” Dad and all my friends continued to yell. After a few moments of back-and-forth in my mind, I decided I’d give the hill a chance. I’d keep a steady hand on the right brake, but it was worth a shot. No one else in front of me had injured anything, so I figured it had to be okay.

Slowly, I let go of the brake handle and gravity started to work its magic. I added a little pedal power to the proceedings, and before you knew it, I was gone faster than the Cincinnati Reds in the playoffs. There was no point in peddling because my silvery-blue Mongoose would have busted apart at the bolts had any more speed entered in the equation.

I sailed down the first hill, hit the trough at the bottom, and went up the hill in front of me. To my surprise, I had picked up so much speed that my bike barely slowed as I went up that hill. Upon reaching the crest, I didn’t even have time to pause and soak up the view from the apex, and before I knew it, I was cruising down the other side at an impressive rate of speed as a smile started to emerge on my face.

Maybe Dad was on to something about this whole “safety be damned” approach to living!

But then, it happened. The grass near the bottom of the hill hadn’t been mowed in quite a few weeks, and burrowed within that tall, green grass was an elevated manhole cover for a nearby water processing building. Unlike the manhole covers you see in the city that are flush with the ground, this one stuck up out of the ground by about a foot.

That’s enough to send you flying if you don’t see it. And I didn’t see a thing.

With an unsuspecting smile on my face from the happiness of finally overcoming a fear and finally feeling triumphant, I nailed that manhole cover without even realizing what had happened. The momentum flung me over the handlebars of my bike, and I landed flat on my back atop that manhole cover. Then, as if the crash itself wasn’t enough embarrassment, the bike continued to flip into the air and then landed on top of me with a thud.

For what I lack in grace, I can make up for in my ability to let out a guttural shriek of pain—which I promptly did after regaining my breath.

The disastrous display left me unable to breathe. My wind was completely knocked out, and I wretched and convulsed on the ground grasping at my chest like I needed an octuple bypass. That was, of course, after my friends and my Dad had run to my side and flung the bike off of me.

All joking aside, I was in about as much pain as you could imagine one would be in after smashing into a manhole cover on a bike and landing atop an unmovable metal and concreate structure. My back had bent in a way that it shouldn’t have bent. I was sore immediately, and knew that this pain was going to last for a couple days.

Aside from the physical pain that I was in, my little ego had also been bruised. It’s never fun to do something stupid; it’s definitely not fun to do something stupid in front of friends that you want to admire you at such an impressionable young age. I had put my lack of athletic ability on display, yet again, in front of my friends who already teased me for being as uncoordinated as a baby giraffe in high heels. I couldn’t help but cry in this moment, and I was waiting for my Dad to ride up and laugh as well.

But good Dads don’t tease when they know that their child is bruised—physically and emotionally.

Without a word, Dad threw his bike to the ground and ran to me. He picked me up into his strong arms, and just held onto me until I could catch my breath again.

“It’s okay, Bub,” he just said until I could breathe again. He started to ask me what was hurting, and I told him that my back really was in a ton of pain. Because my Dad knew me well, he knew when I was faking and when I wasn’t—and in this moment, he knew that I wasn’t.

Without missing a beat, Dad sprung into action mode. I was amazed at how quickly and expeditiously he organized the troops and got us on the move.

“Alright guys, I’m going to need one of you to grab Ty’s bike and walk it home, along with yours. Who’s got it?”

One of my friends piped up and made their way over to my bike, and before I knew it, Dad had picked me up and rested me atop his bike handlebars. We still had about a mile to go to get home, but Dad pushed me cautiously and carefully while cradling me the entire way. I whimpered a bit (because that’s what wimpy little kids like me did), and Dad just kept talking to me to try to get my mind off of things as the hot summer sun started to set.

“Well, Bub,” Dad said, “if it counts for anything, you got some real good height on that front flip!”

Even in the middle of tears, you can’t help but laugh at a line like that.

Eventually, we made it home. Over the next few days, both the bruises to my back and to my ego started to fade—and, in time, my friends and my Dad never let me live down the “bike flip” incident. Every time we saw a manhole cover within 300 feet of us on a ride, they made sure to warn me.

But a good Dad swoops in, picks you up, and carries you when you’re not able to walk. That’s what I felt with my Dad on that day, and more importantly, that’s what I felt from him every time I crashed—both physically and metaphorically.

My Dad was always there to pick me up when I crashed. He did it that day of the bike debacle, and he did it on so many other days. He did it when in moments when I didn’t feel confident in my abilities. He did it after I would fail at an athletic event (he sure had a heck of a lot of opportunities to come to my aid in that category). He did it when I was in college and started having an identity crisis after giving up on my career trajectory of becoming an educator that I had professed since I was young. He did it when I suffered from my own, paralyzing, nine-month bout with clinical anxiety.

Dad never judged. He never criticized me or accused me of wrongdoing or fault when I was hurting. He just swooped in, picked me up, and carried me until I could walk again.

That’s what great Dads do. That’s what my Dad always did—both for me, and for others. That’s what I wish I had done for him more often.

When my Dad crashed as a result of his depression, it was a hard crash. Over time, we were able to see a pretty predictable pattern. My Dad would succumb to his clinical depression, he would shut down, and would even escape by leaving without telling anyone where he had gone. He was afraid to let people know that he was hurting. He was afraid he’d somehow disappoint them. I hate that Dad felt such shame—he didn’t deserve to.

Over time, I learned—we all learned—how to support Dad when he crashed, and I think we learned by watching how he supported all of us. We didn’t get it right every time, but we tried to be there for him because that’s what he always did. My Dad was the guy who was just there for people. He listened, he didn’t judge, he empathized, and he gave us all reassurance and confidence that the crash didn’t define us. That’s what we all tried to do to support Dad. It was imperfectly executed, especially by me, but we tried. We gave it our best effort.

Over time, I learned—we all learned—how to support Dad when he crashed, and I think we learned by watching how he supported all of us. We didn’t get it right every time, but we tried to be there for him because that’s what he always did. My Dad was the guy who was just there for people. He listened, he didn’t judge, he empathized, and he gave us all reassurance and confidence that the crash didn’t define us. That’s what we all tried to do to support Dad. It was imperfectly executed, especially by me, but we tried. We gave it our best effort.

And even though my Dad isn’t here any longer to support me or the people he loved when we inevitably crash, I think one of the best things we can do to honor his memory is to just continue being there. To swoop in when we see someone who is crashing. To serve them. To bolster their spirits, their mind, and their attitude. And, even though it takes a lot of work, we should be there to pick them up and carry them until they feel good enough to walk again.

That was the Scott Bradshaw way. It wasn’t my Dad’s crash that defined him; it was the way he helped others who were crashing that captures his true story.

I love my Dad and miss him desperately, especially in those moments where I’ve felt the same pain of crashing like I did on that day many years ago when I sailed over the handlebars. In a different way, I have felt my Dad there carrying me in all the years that he’s been gone. I have felt him, in those awful moments, continuing to carry me when I can’t walk. When you live a life as big as the one my Dad did, the love doesn’t stop when the heart does. I’m thankful for a Dad that was there to let me crash—because I learned from it. I’m thankful for a Dad that encouraged me to take risks, even if there was a high likelihood that a crash would occur. But more importantly, I’m thankful for a Dad that never turned his back on me when I did crash.

And…I’m pretty thankful for helmets, too.

Dad, The comfort I felt in your arms walking home after my failed-and-unintentional-bike-stunt was a feeling that I can instantly snap back to at any moment—and it’s a feeling that I desperately miss. You were my rock. You were my safe haven. You provided protection from the dangers of the world, but you encouraged me to not play it safe. Dad, thank you for giving me the feeling of safety that allowed me to ride freely. Thank you for being there on all those days when I needed you most. I never questioned whether or not you were at my side, and even since your death, I’ve known that you were there. I think about you each day and wonder what life would look like if you were still here. Even though there’s sadness at that longing, I know that you’re in a place where the pain you experienced here exists no more. I’m thankful that you’re basking in the glow and warmth of Eternity where the pain of crashing is no more. Dad, I love you, and I miss you like crazy. Thanks for always being there for me—both in this world, and in the next. Until I can thank you face-to-face, seeya Bub.

Dad, The comfort I felt in your arms walking home after my failed-and-unintentional-bike-stunt was a feeling that I can instantly snap back to at any moment—and it’s a feeling that I desperately miss. You were my rock. You were my safe haven. You provided protection from the dangers of the world, but you encouraged me to not play it safe. Dad, thank you for giving me the feeling of safety that allowed me to ride freely. Thank you for being there on all those days when I needed you most. I never questioned whether or not you were at my side, and even since your death, I’ve known that you were there. I think about you each day and wonder what life would look like if you were still here. Even though there’s sadness at that longing, I know that you’re in a place where the pain you experienced here exists no more. I’m thankful that you’re basking in the glow and warmth of Eternity where the pain of crashing is no more. Dad, I love you, and I miss you like crazy. Thanks for always being there for me—both in this world, and in the next. Until I can thank you face-to-face, seeya Bub.

“…and if you give what you have to the hungry, and fill the needs of those who suffer, then your light will rise in the darkness, and your darkness will be like the brightest time of day.” Isaiah 58:10 (NLV)

Dad, You lived a big and vibrant life while you were here with all of us, and your absence is even more noticeable and painful because the void left behind is so great. You deserved to live a fuller life than the one you experienced, and I’m sorry I didn’t do more to make that dream reality. Dad, I would have loved watching you grow old—even though it might not have been as much fun for you as it would have been for me. I would have loved seeing you on my wedding day, and you have no idea how much I would have appreciated your wisdom about navigating this new chapter in my life because you were such an amazing husband for Mom. And yes, I would have loved watching you become a grandpa more than anything else. I know you would have been silly and goofy and ridiculous—and completely adored by your grandchildren. But Dad, as much as I wanted to watch those things for myself, I’m ultimately saddened because you earned the right to experience all of those wonderful things. I hate mental illness and suicide for robbing you of these life chapters. Mental illness separated you from us and from many wonderful, beautiful moments that awaited your future. And although I won’t get to watch you enjoy life, and although I’ll always have questions about why this happened to you, I do find peace knowing that you’re not suffering any longer. I find a sense of comfort knowing that the unjustified feelings of shame and embarrassment that you experienced in this world are completely gone and fully redeemed. And I know that as great as any experience you could have had here with us might have been, you’re experiencing a joy and beauty beyond any other as you bask in the glory of Heaven and God’s everlasting love and paradise. Dad, keep watching over me, and keep reassuring me that you were called Home for a reason. I love you, and I wish we could have experienced more of this life together; but I know there’s a greater reward and an unbelievable reunion awaiting us. Thank you Dad, and until the day when we are reunited forever, seeya Bub.

Dad, You lived a big and vibrant life while you were here with all of us, and your absence is even more noticeable and painful because the void left behind is so great. You deserved to live a fuller life than the one you experienced, and I’m sorry I didn’t do more to make that dream reality. Dad, I would have loved watching you grow old—even though it might not have been as much fun for you as it would have been for me. I would have loved seeing you on my wedding day, and you have no idea how much I would have appreciated your wisdom about navigating this new chapter in my life because you were such an amazing husband for Mom. And yes, I would have loved watching you become a grandpa more than anything else. I know you would have been silly and goofy and ridiculous—and completely adored by your grandchildren. But Dad, as much as I wanted to watch those things for myself, I’m ultimately saddened because you earned the right to experience all of those wonderful things. I hate mental illness and suicide for robbing you of these life chapters. Mental illness separated you from us and from many wonderful, beautiful moments that awaited your future. And although I won’t get to watch you enjoy life, and although I’ll always have questions about why this happened to you, I do find peace knowing that you’re not suffering any longer. I find a sense of comfort knowing that the unjustified feelings of shame and embarrassment that you experienced in this world are completely gone and fully redeemed. And I know that as great as any experience you could have had here with us might have been, you’re experiencing a joy and beauty beyond any other as you bask in the glory of Heaven and God’s everlasting love and paradise. Dad, keep watching over me, and keep reassuring me that you were called Home for a reason. I love you, and I wish we could have experienced more of this life together; but I know there’s a greater reward and an unbelievable reunion awaiting us. Thank you Dad, and until the day when we are reunited forever, seeya Bub.

Every single day is difficult—all 1,827 of them; but every single year, July 24 is a date that stares at me from the calendar. It looms in the distance for months, and when it passes, I always breathe a sigh of relief that it’s come and gone. But I know, deep down, that it’s coming again. It will always be there. No particular July 24 has been more or less difficult—just different. But because of the nice, round number, this one feels like a milestone. A milestone I wish I didn’t have to reach.

Every single day is difficult—all 1,827 of them; but every single year, July 24 is a date that stares at me from the calendar. It looms in the distance for months, and when it passes, I always breathe a sigh of relief that it’s come and gone. But I know, deep down, that it’s coming again. It will always be there. No particular July 24 has been more or less difficult—just different. But because of the nice, round number, this one feels like a milestone. A milestone I wish I didn’t have to reach. But guess what? No amount of procrastination could stop that date from coming. No amount of denial could stop me from thinking about what this day represents. This day would come—and yes, it would eventually pass—but the second it did, the clock just begin counting down towards another unfortunate milestone. The next Christmas. The next birthday. The next Father’s Day.

But guess what? No amount of procrastination could stop that date from coming. No amount of denial could stop me from thinking about what this day represents. This day would come—and yes, it would eventually pass—but the second it did, the clock just begin counting down towards another unfortunate milestone. The next Christmas. The next birthday. The next Father’s Day. On the other side of all that grief and sadness, there will be an everlasting love made whole again. On the other side of that grief, there will be a man whom I recognize, smiling and welcoming me into his arms. In that moment, I’ll love never having to say “seeya, Bub” again. That day is coming, although it’s very far off.

On the other side of all that grief and sadness, there will be an everlasting love made whole again. On the other side of that grief, there will be a man whom I recognize, smiling and welcoming me into his arms. In that moment, I’ll love never having to say “seeya, Bub” again. That day is coming, although it’s very far off. Dad, I cry so much when I think that it’s been five years since you and I last talked. Sometimes, those tears are unstoppable. We never even went five days in this life without talking to one another. Dad, it really has felt like an eternity—but sometimes your memory is so real and so vivid that it seems like it was just yesterday when we lost you. But I know the real time. I know that it’s been five whole years since we’ve been able to be in your presence. And life simply isn’t the same without you. We all cling to your memory. We marvel at the things you built and the way you provided for our family. We laugh about the funny things you did to make life more fun. But I also weep when I think about how much life you had left to live. Dad, I’m so sorry that you were sick. I feel horrible that we couldn’t do more to help you find the cure you deserved. I’m sorry that you were robbed of the life you deserved to enjoy. I’ve felt so much guilt in losing you Dad. I know that you don’t want me to feel this way, but I just wish there was more I could have done. You deserved that, Dad. You deserved more, because you gave everything. As painful as these five years have been, Dad, I find peace in the truth of Eternity. I find comfort knowing that you are enjoying God’s eternal glory in a paradise that I can’t even begin to fathom. Dad, thank you for watching over me for these past five years. Thank you for never giving up on me—both in this life, and in the next. Thank you for giving me a lifetime of memories and an example of what fatherhood should be. I love you, Dad. I always did, and I always will. Thank you for loving me back. Until I see you again, seeya Bub.

Dad, I cry so much when I think that it’s been five years since you and I last talked. Sometimes, those tears are unstoppable. We never even went five days in this life without talking to one another. Dad, it really has felt like an eternity—but sometimes your memory is so real and so vivid that it seems like it was just yesterday when we lost you. But I know the real time. I know that it’s been five whole years since we’ve been able to be in your presence. And life simply isn’t the same without you. We all cling to your memory. We marvel at the things you built and the way you provided for our family. We laugh about the funny things you did to make life more fun. But I also weep when I think about how much life you had left to live. Dad, I’m so sorry that you were sick. I feel horrible that we couldn’t do more to help you find the cure you deserved. I’m sorry that you were robbed of the life you deserved to enjoy. I’ve felt so much guilt in losing you Dad. I know that you don’t want me to feel this way, but I just wish there was more I could have done. You deserved that, Dad. You deserved more, because you gave everything. As painful as these five years have been, Dad, I find peace in the truth of Eternity. I find comfort knowing that you are enjoying God’s eternal glory in a paradise that I can’t even begin to fathom. Dad, thank you for watching over me for these past five years. Thank you for never giving up on me—both in this life, and in the next. Thank you for giving me a lifetime of memories and an example of what fatherhood should be. I love you, Dad. I always did, and I always will. Thank you for loving me back. Until I see you again, seeya Bub.

Dad, There have been so many times when I’ve thought about the fear you must have experienced in your life. You were always my Superman—that strong rock and foundation in my life when everything else seemed dangerous. On the outside, you were always “Mr. Fix It,” and I know it bothered you that you couldn’t solve your own struggles with depression. On the surface, you always held everything together—for your family, for your friends, and especially for Mom and I. But Dad, I wish I could have told you that your struggles with mental illness were never a disappointment to any of us. We never thought less of you when you battled with your depression. Sick or healthy, we always loved you and wanted to be near you. You were never a failure to us, Dad. You never failed us, and I wish you had known that more. I am afraid of doing life without you. I have a fear that I can’t do what God is calling me to do to tell your story. But I know that He is with me, and I know that you are with me. I know that you are watching down and pushing me and urging me onward, just as you always did when you were here with us. We all miss you, Dad. We will never stop missing you. You never let me down, and I can’t wait to tell you that in person. Until that day, seeya Bub.

Dad, There have been so many times when I’ve thought about the fear you must have experienced in your life. You were always my Superman—that strong rock and foundation in my life when everything else seemed dangerous. On the outside, you were always “Mr. Fix It,” and I know it bothered you that you couldn’t solve your own struggles with depression. On the surface, you always held everything together—for your family, for your friends, and especially for Mom and I. But Dad, I wish I could have told you that your struggles with mental illness were never a disappointment to any of us. We never thought less of you when you battled with your depression. Sick or healthy, we always loved you and wanted to be near you. You were never a failure to us, Dad. You never failed us, and I wish you had known that more. I am afraid of doing life without you. I have a fear that I can’t do what God is calling me to do to tell your story. But I know that He is with me, and I know that you are with me. I know that you are watching down and pushing me and urging me onward, just as you always did when you were here with us. We all miss you, Dad. We will never stop missing you. You never let me down, and I can’t wait to tell you that in person. Until that day, seeya Bub. Reverend Dan Walters

Reverend Dan Walters

When I was extremely young, my family never took beach vacations. To this day, I’m not sure why because we all loved the beach so much. My very first time seeing the ocean was on a family trip to Panama City, Florida as an eighth grader. Our entire family (grandparents and cousins included) spent a wonderful week on the Gulf Coast, and I remember the momentous nature of that trip, even as a middle schooler. A 12-hour, multi-day car ride had finally concluded, and my Mom and Dad walked me out towards the ocean once we arrived. With my parents, I saw the ocean for the very first time and I got to experience its magnitude. I got to touch sand, and taste saltwater, and splash in the world’s largest pool. Even as a young kid, I appreciated the significance of this experience.

When I was extremely young, my family never took beach vacations. To this day, I’m not sure why because we all loved the beach so much. My very first time seeing the ocean was on a family trip to Panama City, Florida as an eighth grader. Our entire family (grandparents and cousins included) spent a wonderful week on the Gulf Coast, and I remember the momentous nature of that trip, even as a middle schooler. A 12-hour, multi-day car ride had finally concluded, and my Mom and Dad walked me out towards the ocean once we arrived. With my parents, I saw the ocean for the very first time and I got to experience its magnitude. I got to touch sand, and taste saltwater, and splash in the world’s largest pool. Even as a young kid, I appreciated the significance of this experience. After a really, really long drive, my family finally arrived to our condo in Gulf Shores. Shortly after arriving, I think we all knew then that we had found our family vacation spot. There was something about it that made us feel like we were home.

After a really, really long drive, my family finally arrived to our condo in Gulf Shores. Shortly after arriving, I think we all knew then that we had found our family vacation spot. There was something about it that made us feel like we were home. As I’ve written before, Dad was a tremendous athlete. And also as I’ve written before, I was a horrible one. But Dad never let my lack of athleticism curb an opportunity to play. At the beach, Dad and I could throw a frisbee for hours—as long as the wind cooperated. We would warm up close to one another and gradually step back as we threw until we would finally hit a point where we had to wind our torsos like a corkscrew to get the frisbee to sail over the white sand. Dad and I would leap and dive into the sand to catch a frisbee—his leaps and dives always significantly more graceful than mine—and we would yell at each other for not being able to properly hit our target. “Did you actually expect me to catch that?!” we would yell across the beach at one another. “You’re gonna kill a kid with that thing if you don’t learn how to throw it!”

As I’ve written before, Dad was a tremendous athlete. And also as I’ve written before, I was a horrible one. But Dad never let my lack of athleticism curb an opportunity to play. At the beach, Dad and I could throw a frisbee for hours—as long as the wind cooperated. We would warm up close to one another and gradually step back as we threw until we would finally hit a point where we had to wind our torsos like a corkscrew to get the frisbee to sail over the white sand. Dad and I would leap and dive into the sand to catch a frisbee—his leaps and dives always significantly more graceful than mine—and we would yell at each other for not being able to properly hit our target. “Did you actually expect me to catch that?!” we would yell across the beach at one another. “You’re gonna kill a kid with that thing if you don’t learn how to throw it!” And at the beach, Dad never played it safe. More than anything, I think Dad and I probably got the most enjoyment of our daily game of “See Who Can Swim the Furthest Out from the Shore and Make Mom Freak Out the Most” (catchy, no?). Much to my Mom’s displeasure, Dad and I were notorious for jumping into the water and swimming straight ahead until our arms gave out. The water would grow colder and colder the further we would swim, and periodically Dad would stick his arms high above his head and straight-dive down to see if he could still touch the bottom. If he could, we still weren’t out far enough. All the while, my poor Mother would sit anxiously in her beach chair watching our bobbing heads grow smaller and smaller in the waves. The best version of the game was on the beaches where there were life guards on duty, and in those scenarios, we tried to see how loud we could get them to blow their whistles at us! We knew we were really killing the game if we could swim far enough to encounter a deeper sandbar, and if we did, we would sit out on the sandbar and rest until it was time to swim back in. Dad would wave to Mom on occasion from the depths of the mighty ocean, and it was amazing how peaceful the deep ocean water can be. All the ambient noises of the beach fade away when you’re that far out (you especially can’t hear life guard whistles or motherly-shrieks).

And at the beach, Dad never played it safe. More than anything, I think Dad and I probably got the most enjoyment of our daily game of “See Who Can Swim the Furthest Out from the Shore and Make Mom Freak Out the Most” (catchy, no?). Much to my Mom’s displeasure, Dad and I were notorious for jumping into the water and swimming straight ahead until our arms gave out. The water would grow colder and colder the further we would swim, and periodically Dad would stick his arms high above his head and straight-dive down to see if he could still touch the bottom. If he could, we still weren’t out far enough. All the while, my poor Mother would sit anxiously in her beach chair watching our bobbing heads grow smaller and smaller in the waves. The best version of the game was on the beaches where there were life guards on duty, and in those scenarios, we tried to see how loud we could get them to blow their whistles at us! We knew we were really killing the game if we could swim far enough to encounter a deeper sandbar, and if we did, we would sit out on the sandbar and rest until it was time to swim back in. Dad would wave to Mom on occasion from the depths of the mighty ocean, and it was amazing how peaceful the deep ocean water can be. All the ambient noises of the beach fade away when you’re that far out (you especially can’t hear life guard whistles or motherly-shrieks). My Grandpa even told a story at Dad’s funeral about his love for always being the last one up. On occasion, my family would take vacations with our extended family, which included my Grandpa Vern, Grandma Sharon, my Uncle Lee, my Aunt Beth, and my two cousins Jake and Megan. Those were always wonderful vacations, and every day, my Grandpa and my Dad were always the last ones up to the condo. But even my Grandpa couldn’t hang with my Dad.

My Grandpa even told a story at Dad’s funeral about his love for always being the last one up. On occasion, my family would take vacations with our extended family, which included my Grandpa Vern, Grandma Sharon, my Uncle Lee, my Aunt Beth, and my two cousins Jake and Megan. Those were always wonderful vacations, and every day, my Grandpa and my Dad were always the last ones up to the condo. But even my Grandpa couldn’t hang with my Dad. Standing there at the beach, I told Steve how much I missed my Dad. I really didn’t have to say anything, because Steve knew—and he was experiencing the grief himself. Steve had been tremendously close with my entire family, and my Dad treated him just like he would treat his own son. Instead of only crying, though, I was able to share tremendous memories and stories of my Dad, telling Steve all about the funny things he had done at the beach on our family vacations. I shared stories about Dad’s Banana Boat expedition, his wave-runner sandbar collision, and how he was always the last one up for dinner. Little by little, the tears were slowly replaced with a smile and laughter. I didn’t miss him any less; I just had a different focus. Instead of focusing on the loss, I was able to focus on his life. Instead of focusing on the time we didn’t have together, I focused on all the wonderful times we did.

Standing there at the beach, I told Steve how much I missed my Dad. I really didn’t have to say anything, because Steve knew—and he was experiencing the grief himself. Steve had been tremendously close with my entire family, and my Dad treated him just like he would treat his own son. Instead of only crying, though, I was able to share tremendous memories and stories of my Dad, telling Steve all about the funny things he had done at the beach on our family vacations. I shared stories about Dad’s Banana Boat expedition, his wave-runner sandbar collision, and how he was always the last one up for dinner. Little by little, the tears were slowly replaced with a smile and laughter. I didn’t miss him any less; I just had a different focus. Instead of focusing on the loss, I was able to focus on his life. Instead of focusing on the time we didn’t have together, I focused on all the wonderful times we did. I spend a lot of time on the beach during dusk as many of the families on the shore will begin to retreat to their condos. And I do this for a simple reason: that’s what Dad would have done. I’ve learned why he loved it so much. As the beach starts to quiet down from a busy day of frivolity and fun, there’s a quiet stillness that begins to wash across the shore. That stillness is enticing and comforting, and it’s in those moments that I often feel closest to God. And I think about how peaceful those moments must have been to a man who struggled with depression. Dad treasured that peace. And now, I treasure the memory of his life during those peaceful moments, and I try to live it out every chance I get.

I spend a lot of time on the beach during dusk as many of the families on the shore will begin to retreat to their condos. And I do this for a simple reason: that’s what Dad would have done. I’ve learned why he loved it so much. As the beach starts to quiet down from a busy day of frivolity and fun, there’s a quiet stillness that begins to wash across the shore. That stillness is enticing and comforting, and it’s in those moments that I often feel closest to God. And I think about how peaceful those moments must have been to a man who struggled with depression. Dad treasured that peace. And now, I treasure the memory of his life during those peaceful moments, and I try to live it out every chance I get. Dad, there has never been a time when I’ve gone to the beach without thinking of you—and there never will be. You made our time at the beach together so memorable, but more than that, you taught me so many important life lessons while we were there. You taught me to slow down and relax. You taught me to soak in God’s beautiful creation. You taught me to be kind to people and get to know them, because God created them, too. You taught me to let go of all the busy things from back home and simply enjoy the life that was in front of me in that moment. I take these lessons with me everywhere I go, but especially when I go to the beach. Even though I’m still able to have fun when I go, it just isn’t the same without you. I miss our throwing sessions, and sometimes I’ll just carry a baseball in my backpack to turn over and over in my hands and think of the time we spent together. I miss trying to see who could swim the furthest out, and watching you beckon me further even when I felt like I couldn’t keep swimming. I miss walking along the shoreline with you and listening to your stories about oil rigs in the distance or planes flying overhead. You had an inquisitive, appreciative spirit for all life had to offer. And more than anything, I miss watching you enjoy those moments on the shore by yourself being the last one up. It’s strange, but sometimes it’s like I look down from the balcony and I can still see you sitting there. Dad, I know you’re still with me. I know that you’re guiding me and watching over me in everything that I do. Thank you for always being my best teacher. Thank you for being a Dad unlike any other. And thank you for always teaching me that the last one up wins. I love you, Dad. I miss you tremendously. I sure hope there are beaches in heaven, because if there are, I promise I’m going to swim further out than you. Until that day when we can be beachside together again, seeya Bub.

Dad, there has never been a time when I’ve gone to the beach without thinking of you—and there never will be. You made our time at the beach together so memorable, but more than that, you taught me so many important life lessons while we were there. You taught me to slow down and relax. You taught me to soak in God’s beautiful creation. You taught me to be kind to people and get to know them, because God created them, too. You taught me to let go of all the busy things from back home and simply enjoy the life that was in front of me in that moment. I take these lessons with me everywhere I go, but especially when I go to the beach. Even though I’m still able to have fun when I go, it just isn’t the same without you. I miss our throwing sessions, and sometimes I’ll just carry a baseball in my backpack to turn over and over in my hands and think of the time we spent together. I miss trying to see who could swim the furthest out, and watching you beckon me further even when I felt like I couldn’t keep swimming. I miss walking along the shoreline with you and listening to your stories about oil rigs in the distance or planes flying overhead. You had an inquisitive, appreciative spirit for all life had to offer. And more than anything, I miss watching you enjoy those moments on the shore by yourself being the last one up. It’s strange, but sometimes it’s like I look down from the balcony and I can still see you sitting there. Dad, I know you’re still with me. I know that you’re guiding me and watching over me in everything that I do. Thank you for always being my best teacher. Thank you for being a Dad unlike any other. And thank you for always teaching me that the last one up wins. I love you, Dad. I miss you tremendously. I sure hope there are beaches in heaven, because if there are, I promise I’m going to swim further out than you. Until that day when we can be beachside together again, seeya Bub.

Dad, I wish you could have read Reverend Walters’ book and heard his story, because I think you felt many of the things he did. I know you struggled with how to share your hurt and your pain because you didn’t want to appear weak. You didn’t want people to think you were a failure. Dad, you never failed any of us—ever. You had an illness that you couldn’t understand, and I wish we had done more to help you escape the trap that forced you into silent suffering. But Dad, I know that our Heavenly Father has welcome you into His loving arms. I know that He is redeeming your story day by day with each individual who loves you and learns from you. Dad, I will never stop loving you. I will never stop trying to find ways to help those who are hurting like you were. Keep watching over me, because I can feel it. Until I can tell you how much you are loved face-to-face, seeya Bub.

Dad, I wish you could have read Reverend Walters’ book and heard his story, because I think you felt many of the things he did. I know you struggled with how to share your hurt and your pain because you didn’t want to appear weak. You didn’t want people to think you were a failure. Dad, you never failed any of us—ever. You had an illness that you couldn’t understand, and I wish we had done more to help you escape the trap that forced you into silent suffering. But Dad, I know that our Heavenly Father has welcome you into His loving arms. I know that He is redeeming your story day by day with each individual who loves you and learns from you. Dad, I will never stop loving you. I will never stop trying to find ways to help those who are hurting like you were. Keep watching over me, because I can feel it. Until I can tell you how much you are loved face-to-face, seeya Bub.  Reverend Dan Walters

Reverend Dan Walters

Dad, There are so many days when I wish I could snap my fingers and have my old life back. The life when you existed here on Earth. I wish that I could have lunch with you, or go on a bike ride, or listen to country music together, or sit by the bonfire. I wish I could hear your laugh again. I wish I could feel you rub my head when you left for work in the morning. I wish that these memories weren’t memories, but instead were real life. But I know life is difficult, and I am amazingly grateful that I can look back over the twenty-six years we spent together and know that you gave every ounce of love you had, each and every day. Ironically, you being in my life prepared me to live life without you. You taught me to enjoy life in spite of hard circumstances or difficult moments. When times get tough, especially when I think about losing you, I’m able to resort to the things you taught me. I’m able to remember the appreciation you had for life’s little moments. And I smile. Sometimes through tears, but I’m smiling nonetheless. I have you to thank for that smile, and so much more. Until I can thank you again in person and experience a new Dad Day that will last through eternity, seeya Bub.

Dad, There are so many days when I wish I could snap my fingers and have my old life back. The life when you existed here on Earth. I wish that I could have lunch with you, or go on a bike ride, or listen to country music together, or sit by the bonfire. I wish I could hear your laugh again. I wish I could feel you rub my head when you left for work in the morning. I wish that these memories weren’t memories, but instead were real life. But I know life is difficult, and I am amazingly grateful that I can look back over the twenty-six years we spent together and know that you gave every ounce of love you had, each and every day. Ironically, you being in my life prepared me to live life without you. You taught me to enjoy life in spite of hard circumstances or difficult moments. When times get tough, especially when I think about losing you, I’m able to resort to the things you taught me. I’m able to remember the appreciation you had for life’s little moments. And I smile. Sometimes through tears, but I’m smiling nonetheless. I have you to thank for that smile, and so much more. Until I can thank you again in person and experience a new Dad Day that will last through eternity, seeya Bub.

Dad, Although I miss you terribly, I am envious that you are living in the absolute perfection of heaven where all your pain is gone. I know that you are now in a perfect relationship with God—the one that he intended when he created mankind. I hope that I can find the strength to bring this world as close to that perfection as humanly possible. I think about all the times that I didn’t support you when you were suffering the way I should have, and for that I will always be sorry. But, I’m doing my best to make up for my shortcomings. I’m trying to be to others what I wish I would have been to you all along. Dad, I wish I could have created a place where you felt it was okay to admit that you weren’t feeling well and that you were hurting. I promise to make that a reality for all those who are still suffering. And I’ll honor your memory all along the way. Until I can see you and tell you all these things face to face, I’ll always love you. Seeya, Bub.

Dad, Although I miss you terribly, I am envious that you are living in the absolute perfection of heaven where all your pain is gone. I know that you are now in a perfect relationship with God—the one that he intended when he created mankind. I hope that I can find the strength to bring this world as close to that perfection as humanly possible. I think about all the times that I didn’t support you when you were suffering the way I should have, and for that I will always be sorry. But, I’m doing my best to make up for my shortcomings. I’m trying to be to others what I wish I would have been to you all along. Dad, I wish I could have created a place where you felt it was okay to admit that you weren’t feeling well and that you were hurting. I promise to make that a reality for all those who are still suffering. And I’ll honor your memory all along the way. Until I can see you and tell you all these things face to face, I’ll always love you. Seeya, Bub.

Dad, Even though I know you would tell me not to feel regret, I do wish that I had the chance to hit the “do-over” button on so many things in my life. I wish I had been more of a support to you when you needed me. I wish that I had spent more time with you doing the things you loved to do. I wish that I could have done more to help you find peace and solace in the tumult of your depression. I don’t know the answer to why this terrible tragedy happened, but I do know that God has a plan to make something good out of it. I often wonder what could possibly be better than more time with you, but I know that although I feel a horrible separation from you in these moments, there will come a day when you and I can both live completely free of regret and goodbyes. I long for that day, but until then, seeya Bub.

Dad, Even though I know you would tell me not to feel regret, I do wish that I had the chance to hit the “do-over” button on so many things in my life. I wish I had been more of a support to you when you needed me. I wish that I had spent more time with you doing the things you loved to do. I wish that I could have done more to help you find peace and solace in the tumult of your depression. I don’t know the answer to why this terrible tragedy happened, but I do know that God has a plan to make something good out of it. I often wonder what could possibly be better than more time with you, but I know that although I feel a horrible separation from you in these moments, there will come a day when you and I can both live completely free of regret and goodbyes. I long for that day, but until then, seeya Bub.