The tiniest, simplest books are often the best books.

When I was a kid, one of my favorite books was one that my Mom bought for me at a library book sale called “Love Is Walking Hand in Hand.” The 1965 book is about as simple as you can get. Written by the famous illustrator Charles Schulz, the book features the Peanuts gang (Charlie Brown and Snoopy and all your other favorites) with simple but practical examples of what love can look like in our everyday lives. Each page features a new example: “Love is walking hand in hand,” “Love is having a special song,” “Love is messing up someone’s hair,” “Love is wishing you had nerve enough to go over and talk with that little girl with the red hair,” “Love is letting him win even though you know you could slaughter him” (There’s more awesome gems from this book at brainpickings.org).

When I was a kid, one of my favorite books was one that my Mom bought for me at a library book sale called “Love Is Walking Hand in Hand.” The 1965 book is about as simple as you can get. Written by the famous illustrator Charles Schulz, the book features the Peanuts gang (Charlie Brown and Snoopy and all your other favorites) with simple but practical examples of what love can look like in our everyday lives. Each page features a new example: “Love is walking hand in hand,” “Love is having a special song,” “Love is messing up someone’s hair,” “Love is wishing you had nerve enough to go over and talk with that little girl with the red hair,” “Love is letting him win even though you know you could slaughter him” (There’s more awesome gems from this book at brainpickings.org).

I loved that book because it was easy. I loved that book because it took a complex and nebulous idea, like love, and made it easy for me to see and understand. That book put hands and feet on love for me. That book didn’t just tell me what love was—it taught me how to love other people.

Isn’t it funny how we often come back to those simple little lessons as we age to deal with some of life’s most complex issues?

It’s true, my life after Dad’s death has been vastly more complicated, but the answers to those complicated questions can sometimes be beautifully, wonderfully simple.

Lately, I’ve been reading and revisiting a number of different books and articles written by survivors of suicide. Some of these books resonate really deeply with me, but others describe scenarios that I’m truly unfamiliar with. And it should be that way. The experience of each survivor of suicide is entirely different, and we all struggle with different feelings at different seasons. There’s no manual or “right way” to grieve. There’s no perfect way to do this because each person who suffers is imperfect in their own way.

One thing that we all have in common as survivors of suicide loss, however, is dealing with questions. And one of the worst ramifications of a suicide involves the many unanswered (and sometimes unanswerable) questions it creates in the lives of those left behind.

There is one question in the “life after your loved one” that is particularly haunting. It’s a question that gets to the roots and the motivations of suicide in general.

Oftentimes, whether reasonable or not, suicide survivors often wonder “If my loved one died by suicide, did they ever really love me?”

It’s heartbreaking for me to even write these questions down, mainly because this is a question that I’ve always been able to answer easily. Yes, I know that my Dad loved me. I know that he suffered from a debilitating brain illness that warped his mind and hacked his thought processes. I know that his decision was not a reflection of his love or lack thereof. It was uncontrollable. It was out of his ability to handle. He loved me so much that he couldn’t bear the thought of letting me (and the rest of his friends and family) down.

But even the most rock-solid faith in God and love can be subject to temptation and doubt. No matter how strong my belief, I have to admit…there have been moments in the three-and-more years since Dad passed where Satan has gotten the best of me. There have been moments so sad and heartbreaking that it’s made it hard to function, physically and emotionally. And yes, although I hate to admit it, there have been moments where (even temporarily) the pain of losing my Dad so suddenly and tragically have called into question everything I believe.

Alright, I’ll say it…I’ve always been the guy who rolls my eyes a bit at a wedding whenever the minister says “Our reading is from the 13th chapter of the book of 1st Corinthians…” Mainly, I used to think that people chose this particular passage because it’s the easiest one to understand. It’s easy to reprint on a coffee mug or desk sign. (Don’t act like I’m the only one who’s thought this.)

But suicide changed my life in dramatic ways, and that particular passage of Scripture took on a whole new meaning after Dad died. You’ve heard it before, and just to help you prepare for the Summer wedding season, you’ll hear it again here:

“Love is patient and kind; love does not envy or boast; it is not arrogant or rude. It does not insist on its own way; it is not irritable or resentful; it does not rejoice at wrongdoing but rejoices with the truth. Love bears all things, believes all things, hopes all things, endures all things. Love never ends.” 1 Corinthians 13:4-8 (ESV)

I think people love this verse because, just like my Charlie Brown book from my childhood, it makes love a tangible thing. It puts hands and feet to love. We can look at any scenario in our life, evaluate it against these standards, and judge accurately whether or not love is there.

For this reason, I often go to the version in The Message (MSG) that I think puts a perfect “Charlie Brown” picture with the original text:

“Love never gives up. Love cares more for others than for self. Love doesn’t want what it doesn’t have. Love doesn’t strut, doesn’t have a swelled head, doesn’t force itself on others, isn’t always ‘me first,’ doesn’t fly off the handle, doesn’t keep score of the sins of others, doesn’t revel when others grovel, takes pleasure in the flowering of truth, puts up with anything, trusts God always, always looks for the best, never looks back, but keeps going to the end. Love never dies.” 1 Corinthians 13: 4-8 (MSG)

So, like I’ve done so many times when the storms have come upon my soul after Dad died, I did just that to help reaffirm and strengthen my beliefs. Did my Dad really, really love me? Of course he did. Did he love me even though he died from suicide? Yes, undoubtedly. Even though life might have seemed unlivable to him, did he still love me?

Yes, yes, yes. I can answer that question with the firmest of faith. And it’s not just a whim or a feeling. It’s a fact. I can evaluate my Dad and his actions as a father against this beautiful, poetic Scripture, and I can know beyond a shadow of a doubt that he loved me…and loves me still.

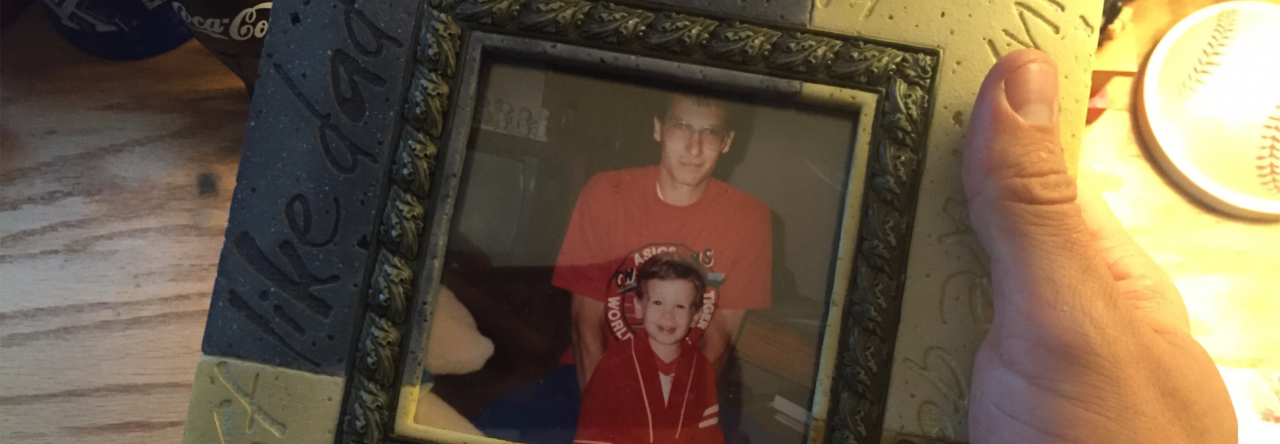

“Love is patient…” (v. 4) Boy, was my Dad ever patient…with me and with everything in life. All throughout my childhood, my Dad never tired of doing things that I’m sure weren’t all that exciting for him. I think specifically of the hours we used to spend each night wrestling on the floor of our family room. Much to Mom’s chagrin, I would often jump off of the stairs or the arm of a couch and Dad would catch me and body slam me. I think of all the times that Dad would take me to the playground or toss me off the deck of our backyard swimming pool. I’m sure that there were other things he would have rather done as an adult. But he always took the time to let me be a child. He was always patient with my constant pleas for entertainment. He was patient in everything he did, but I never once felt like I was a burden or distraction for my Dad.

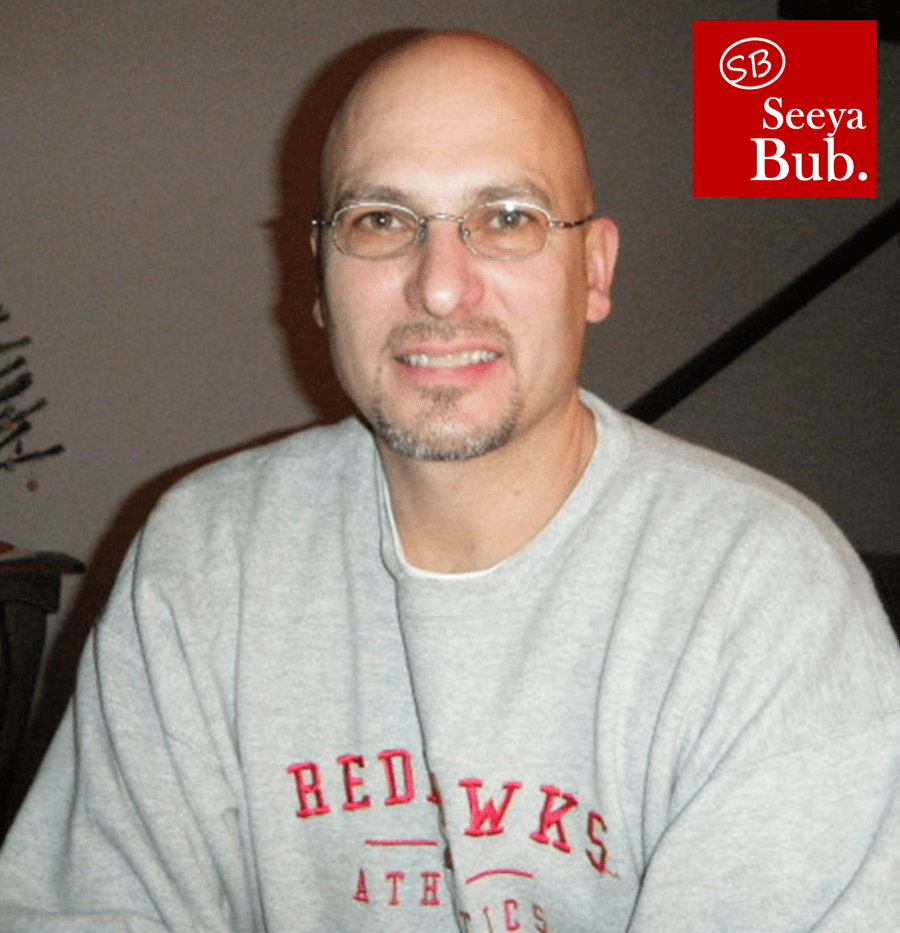

“Love is kind.” (v. 4) I remember from a very young age, that my Dad always taught me how to be gentle. He didn’t tell me what being gentle was; he simply showed me in the way he lived his life. My Dad had a heart for other people. In my opinion, kindness is often judged by how you treat people who can’t ever pay you back for your kindness. My Dad had a heart for those people—especially the physically disabled. I remember how special his relationship was with Madelyn, a young girl from our church who suffered from Down’s Syndrome. He loved seeing her and each time, he would bend his neck to let her rub his bald head as she smiled. My Dad also loved pets and animals of all kinds. Dad was never too busy to pet a dog or play fetch with it. He got so much enjoyment giving joy to other people (and many four-legged creatures as well).

Whenever I think of my Dad’s kindness, I think most about the times when I was hurt or injured as a child, and how he could make me feel safe, secure, and steady again. Dad often took me and my friends on bike rides to Rentschler Park when we were kids. My friends and I loved it, because Dad would often take us on the most challenging trails, encouraging us to pop wheelies, ramp small hills, and navigate particularly treacherous trails. One evening, I rode down a very steep hill, and the overgrown grass had concealed a rather large and raised manhole cover. I hit the manhole cover hard, went head over handlebars, and landed on top of the manhole cover on my back as the bike slammed down hard into my chest. I got the wind knocked out of me, and I had a lot of cuts and bruises to show for it. Without blinking, my Dad threw his bike down, came and scooped me up in his arms, and carried me all the way home. He enlisted my friends to help push our bikes so he could carry me. That’s kindness. That’s love. That’s my Dad. I miss feeling the kindness of his hug.

“Love does not envy or boast. It is not arrogant or rude.” (v. 4) The message translation of this portion says “Love doesn’t strut, doesn’t have a swelled head” (v. 4-5). I love that! My Dad was one of the most humble men I’ve ever met, and his entire life was centered around telling people how proud he was of me—sometimes to the point that it embarrassed me! Although he didn’t have much to brag on when it came to athletic achievements, there were the few miraculous Saturdays where I had a good day in the net as the keeper and he would tell everyone about my achievement. Whether it was a great report card, an award I won at the school, or a particularly strong drawing I had made as a child, I always knew that Dad was my biggest fan. He loved me for who I was, and he loved telling people about the things I was doing. It made me feel important. It made me feel special. My Dad’s love was always, always about other people.

“It does not insist on its own way.” (v. 5) My Dad always gave me the freedom to figure things out on my own. He loved me by letting me make mistakes. Ultimately, he loved me by letting me be me. Dad and I were similar in many ways, but we were also very different. Dad was a stellar athlete. I was…less than stellar. Dad was a builder and knew how to work with his hands. I complained about most physical labor and threatened to call Children’s Protective Services if he forced me to work. Dad enjoyed riding dirtbikes and motorcycles, and although he bought me my own to ride many times, I was often too nervous to ride them well. But Dad, in spite of all these differences, always loved me. He never made me feel inadequate because I enjoyed books or puppet shows or coloring or things that I’m sure he didn’t have an interest in. I think Dad loved that I was like him in many ways, but I know that he also loved me because I wasn’t a carbon copy of him.

“It is not irritable or resentful.” (v. 5) I am a lucky child in that I can’t really remember my Dad ever losing his temper with me. I look back on my life, and yes there were times where he was upset with me, but I never felt unloved. For the most part, I was a pretty good kid—but even the best of kids do something every now and then to send their parents into the stratosphere. Even when I made mistakes, Dad never let those mistakes influence how he felt about me or how he perceived my character. My Dad was the parent who could get his point across just by saying he was disappointed in me and the way I behaved. He loved me, and yes he disciplined me when I needed and deserved it, but he never lost his temper. I strive to be more like him in many ways, but especially in this way. I know I need more of his coolheadedness.

“It does not rejoice at wrongdoing but rejoices with the truth.” (v. 6) In everything he did and taught me, my Dad encouraged me to be a good person. I know that sounds simple, but because he loved me, he wanted me to love other people and do what was right by them. Dad’s actions were always evaluated in the context of how it might affect other people. It might sound like a minor lesson to some people, but my Dad refused to litter. And he also refused to let his son do the same thing. At the time, I didn’t understand how throwing a gum wrapper out the car window could be a big deal, but Dad cared too much about the planet and other people to make his garbage their problem. And yes, if I threw down a candy wrapper or Coke can behind my Dad’s back, he would make me walk all the way back and pick it up. In even the minor, day-to-day actions of life, my Dad taught me to think about other people. He loved me by helping me love others and care for their well being.

“Love bears all things, believes all things, hopes all things…” (v. 7) The Message translation from this portion of the passage says that love “always looks for the best” and “never looks back.” My Dad was an eternal optimist, especially when it came to seeing the goodness in other people. I’m thankful that my Dad always saw the best in me, even when I didn’t always show him my best. When it came to emotions and arguments that happen between a father and son, my Dad had an unbelievably short memory. If Dad and I had a disagreement on Friday night, Dad would be completely back to his normal, smiling self by that Saturday morning. He never, ever withheld his love, because he knew love could solve all of our problems. He knew that he could reach me by loving me, not by shunning me. He let love cover every interaction we ever had. I wish I had always done the same.

“Love endures all things.” (v. 7) I can think of few things that could have devastated my life more than losing one of my parents, but strangely enough I still felt that the love my Dad showed me each and every day could carry me through the pain of losing him. Strangely, the love he showed me helped prepare me for eventually losing him. I watched the way my Dad treated me when I was hurting, and in turn I learned how to better comfort my Mom and other family members when they were grieving. My Dad had the uncanny ability to nurture me authentically, and when he died I knew that one of the central callings of my life would be to love people the way he did.

“Love never ends.” (v. 8) My Dad’s life here on Earth might have ended, but I know that his love never has. It’s still with me. I feel it every single day. On certain days, I can still feel him talking to me. I don’t know if it’s Scripturally or theologically sound, but I’ve felt messages of love from my Dad numerous times since he died—especially in the dark moments where I needed them most. I think this is the greatest reflection of a person’s capacity to love—the body may be gone, but the heart and the soul are still here when you need them. When I lack confidence or feel nervous, I can still picture my Dad standing there with a huge smile on his face saying “I’m proud of you, Bub.” That’s all I need. That’s all I’ll ever need.

I’ve often heard that the best way to fight the Devil and the doubt he creates is to attack him with Scripture. This battle tactic isn’t a speculation…it’s directly evidenced when Jesus was tempted in the wilderness (Matthew 4 or Luke 4). When Satan tempted Jesus with food or power, and even pushed him to test God’s love for him by jumping from the Temple and calling on Angels to rescue him, Jesus fought back by quoting the word of God. Satan tried to create doubt, but Jesus relied on the unfailing truth of God’s Word to bolster his spirit. And it worked.

Doubt is, unfortunately, natural in the life of a suicide survivor. When something as unthinkable as a suicide happens to someone we love, it’s easy to question everything that previously seemed to be real or true. “If that could happen,” the suicide survivor says, “then how can I trust anything else I’ve ever believed?” It sounds dramatic, but I’ve experienced it myself…as have millions of others who are left behind with this heartache.

I’m so thankful, though, that in the midst of all my heartache and doubt and confusion I can know without question that, yes, my Dad loved me and that, yes, he still loves me.

My Dad’s death from suicide was not a conscious decision, but one that occurred in the middle of a terrible storm and illness that took over his thought processes. If anything, I think my Dad’s love for us might have been so strong that he didn’t want his illness to be a burden to me or Mom or the rest of our family. I wish that I had told him that he would never be a burden, and that one of the greatest gifts in my life was receiving his love.

Why would I ever let one defeat like my Dad’s death erase a lifetime of evidence that proves he was loving and caring and kind? One moment does not define a person’s entirety. Suicide, although permanent and irreversible in this situation, does not tell my Dad’s story. The love he showed is what defines him. The love he gave made him the man he was. It’s making me into a better man even though he’s gone.

So yes, amidst all the doubt and confusion that a suicide creates, I know my Dad loved me. I know that he still loves me. It’s there in the pages of my Bible. It’s reflected in the moments of my life. It’s in everything I do, and it always will be.

Dad, I hate that the confusion over your death would even lead to any doubt about whether or not you loved me, but I’m glad that I can quickly rely on the truth of God’s Word and the example you gave me each and every day to reaffirm your love. You were the epitome of a loving Father. I try each day to love people the way you did, and no matter how hard I try I know that I’ll always fall short—that’s how high you set the bar. You made love your mission. You made love your calling. You let God show you how to love, and then you showed God’s people how to love in everything you did. I pray that I’m able to become more and more like you as days go by. As those days pass, I rest assured knowing I will get to see you again. I’ll get to feel your hug and see your smile and know that everything about you is right, even though your circumstances here on Earth weren’t. Keep loving me, Dad. Keep watching over me and pushing me to be a better man. I’ll never stop loving you. Until I can tell you in person, seeya Bub.

Dad, I hate that the confusion over your death would even lead to any doubt about whether or not you loved me, but I’m glad that I can quickly rely on the truth of God’s Word and the example you gave me each and every day to reaffirm your love. You were the epitome of a loving Father. I try each day to love people the way you did, and no matter how hard I try I know that I’ll always fall short—that’s how high you set the bar. You made love your mission. You made love your calling. You let God show you how to love, and then you showed God’s people how to love in everything you did. I pray that I’m able to become more and more like you as days go by. As those days pass, I rest assured knowing I will get to see you again. I’ll get to feel your hug and see your smile and know that everything about you is right, even though your circumstances here on Earth weren’t. Keep loving me, Dad. Keep watching over me and pushing me to be a better man. I’ll never stop loving you. Until I can tell you in person, seeya Bub.

“And now these three remain: faith, hope and love. But the greatest of these is love.” 1 Corinthians 13:13 (NIV)

Dad, Each day I wrestle with telling your story and making sure people who never knew you know the type of man you were. I want them to know you were strong. I want them to know you were thoughtful. I want them to know you were caring and loving and everything a Father should be. I hope that the words I choose to use convey the love I have for you and the love you gave to all of us each and every day here on Earth. You never inflicted pain with the words you chose. You built people up by telling them and showing them how important they were to you. You and I had many wonderful conversations together, and we shared so many words. I’m sorry for the moments that my words may have hurt you. I wish I had spent more time telling you the words you deserved to hear—that I loved you, that I was proud of you, and that I was always there to listen when you were hurting. I know that we will have these conversations again. I wait longingly for that day. But until our words meet each other’s ears again, seeya Bub.

Dad, Each day I wrestle with telling your story and making sure people who never knew you know the type of man you were. I want them to know you were strong. I want them to know you were thoughtful. I want them to know you were caring and loving and everything a Father should be. I hope that the words I choose to use convey the love I have for you and the love you gave to all of us each and every day here on Earth. You never inflicted pain with the words you chose. You built people up by telling them and showing them how important they were to you. You and I had many wonderful conversations together, and we shared so many words. I’m sorry for the moments that my words may have hurt you. I wish I had spent more time telling you the words you deserved to hear—that I loved you, that I was proud of you, and that I was always there to listen when you were hurting. I know that we will have these conversations again. I wait longingly for that day. But until our words meet each other’s ears again, seeya Bub.

Dad, It still doesn’t seem right that this is the fourth birthday that’s passed since you left us. It doesn’t feel right that life is going on without you. There are times when my heart feels so much pain that I can’t imagine ever celebrating anything without you again. But, in a weird way, I’m thankful for this pain because it reminds me how special you made life feel while you were here. You brought a vivid color and energy to my life each and every day that I don’t know I’ll ever be able to experience until I see you again. But I will see you again. I’ll make up for all those birthdays that I wished I could do over. You and I will, one day, celebrate our new birthdays in heaven. And fortunately, we will never, ever, see those birthdays come to an end. Happy birthday, Bub. You live on in my heart each and every day. Until I can tell you this face to face once again, seeya Bub.

Dad, It still doesn’t seem right that this is the fourth birthday that’s passed since you left us. It doesn’t feel right that life is going on without you. There are times when my heart feels so much pain that I can’t imagine ever celebrating anything without you again. But, in a weird way, I’m thankful for this pain because it reminds me how special you made life feel while you were here. You brought a vivid color and energy to my life each and every day that I don’t know I’ll ever be able to experience until I see you again. But I will see you again. I’ll make up for all those birthdays that I wished I could do over. You and I will, one day, celebrate our new birthdays in heaven. And fortunately, we will never, ever, see those birthdays come to an end. Happy birthday, Bub. You live on in my heart each and every day. Until I can tell you this face to face once again, seeya Bub.

God has given me so many wonderful blessings in this life, but none greater than the two loving parents that have been with me since before I took my first breath. I’ve always had a special connection with my Mom since I was little. As an only child, I was fortunate to have all of her love and attention. I’m thankful that even though I’m growing older, I’ve never stopped receiving that.

God has given me so many wonderful blessings in this life, but none greater than the two loving parents that have been with me since before I took my first breath. I’ve always had a special connection with my Mom since I was little. As an only child, I was fortunate to have all of her love and attention. I’m thankful that even though I’m growing older, I’ve never stopped receiving that. Farm (for those of you who are old enough to remember this place), picnics, movies, making crafts, zoo trips and much more. Birthdays and holidays were also special times at the Bradshaw house. Scott and I always wanted to make Tyler’s birthdays special. Every year we would plan a big birthday party for him, and Scott was always excited and would always try to plan something different each year.

Farm (for those of you who are old enough to remember this place), picnics, movies, making crafts, zoo trips and much more. Birthdays and holidays were also special times at the Bradshaw house. Scott and I always wanted to make Tyler’s birthdays special. Every year we would plan a big birthday party for him, and Scott was always excited and would always try to plan something different each year. Dad, I always pictured you growing old with Mom. I knew you would make a tremendous Grandpa, but just as importantly I know that Mom will be an amazing Grandma someday. I hate that you didn’t get to enjoy this chapter of life here on this Earth with her. But I know that you are so unbelievably proud of her as you watch how she’s handled the troubles of this life without you. I know that you are watching over her each and every day. She is lucky to have such an amazing guardian angel. It doesn’t change the fact that we would rather have you here with us, but it does make life easier to handle knowing that, someday, we will all be reunited—a family again. Although we don’t have you here with us, we will always cherish and hold near to our hearts the memories that you gave us. You gave us so many. Thank you for always doing that. Thank you for being a wonderful Father, and thank you for choosing the best Mother any kid could ever hope for. Until we get to relive those wonderful memories together again, seeya Bub.

Dad, I always pictured you growing old with Mom. I knew you would make a tremendous Grandpa, but just as importantly I know that Mom will be an amazing Grandma someday. I hate that you didn’t get to enjoy this chapter of life here on this Earth with her. But I know that you are so unbelievably proud of her as you watch how she’s handled the troubles of this life without you. I know that you are watching over her each and every day. She is lucky to have such an amazing guardian angel. It doesn’t change the fact that we would rather have you here with us, but it does make life easier to handle knowing that, someday, we will all be reunited—a family again. Although we don’t have you here with us, we will always cherish and hold near to our hearts the memories that you gave us. You gave us so many. Thank you for always doing that. Thank you for being a wonderful Father, and thank you for choosing the best Mother any kid could ever hope for. Until we get to relive those wonderful memories together again, seeya Bub.  Becky Bradshaw

Becky Bradshaw

Dad, I can’t even begin to tell you how much I miss seeing you at my games. I may not have always shown it like I should have, but I always loved having you there. You made it a priority to come and hear me announce, and you didn’t do it out of obligation—you did it because you loved me. You did it because you enjoyed the simple moments that life provided. Every time I look down at the grandstand at a Joes game, I picture you sitting there. Every time I announce a game at Miami Hamilton, I can still see you strolling across the court towards me once the game ends. I long for the day where I can be there at a game with you again. If there are baseball games in heaven, I can’t wait to sit next to you and enjoy one together. But for now, seeya Bub.

Dad, I can’t even begin to tell you how much I miss seeing you at my games. I may not have always shown it like I should have, but I always loved having you there. You made it a priority to come and hear me announce, and you didn’t do it out of obligation—you did it because you loved me. You did it because you enjoyed the simple moments that life provided. Every time I look down at the grandstand at a Joes game, I picture you sitting there. Every time I announce a game at Miami Hamilton, I can still see you strolling across the court towards me once the game ends. I long for the day where I can be there at a game with you again. If there are baseball games in heaven, I can’t wait to sit next to you and enjoy one together. But for now, seeya Bub.

Dad, What I wouldn’t give to hear you sing another song right next to me. What I wouldn’t give to go back to those days where we would ride around in your truck and listen to country music together. I’m thankful that you always set the right example for me in church by singing along with the worship songs. I’m thankful that you always remembered that singing songs of praise and worship aren’t about us but are about developing a relationship with God. Certain songs come on the radio, and I still think of you. I’ll always be appreciative of the memories you gave me as a young child listening to country music in your truck. Thank you for being a Dad who always had a song of love in your heart. Until we both join the chorus of heavenly angels together, seeya Bub.

Dad, What I wouldn’t give to hear you sing another song right next to me. What I wouldn’t give to go back to those days where we would ride around in your truck and listen to country music together. I’m thankful that you always set the right example for me in church by singing along with the worship songs. I’m thankful that you always remembered that singing songs of praise and worship aren’t about us but are about developing a relationship with God. Certain songs come on the radio, and I still think of you. I’ll always be appreciative of the memories you gave me as a young child listening to country music in your truck. Thank you for being a Dad who always had a song of love in your heart. Until we both join the chorus of heavenly angels together, seeya Bub.

Dad, I always admired your energy and vitality. You attacked life and took on new challenges, and you were never that Dad who loved the couch more than he loved spending time with his family. In your life, you always seemed to be able to find a good balance between rest and being active, but when you were active, you always made the most of it and there was always a huge smile on your face. Whether it was riding bikes, walking the dog, playing softball, schooling a bunch of youngsters in basketball, or simply goofing around in the backyard swimming pool, you realized that life was designed to be lived. Even though I didn’t always listen (and boy do I wish I would have), you always encouraged me to get up and get going. You always encouraged me to believe there was life outside of a TV set or computer screen, and since you left I’ve tried to live this out. I’m looking forward to many bike rides together on the other side of Eternity. And if you could talk to the Big Guy upstairs and have him send me a little more muscle mass, I’d be appreciative. Until then, seeya Bub.

Dad, I always admired your energy and vitality. You attacked life and took on new challenges, and you were never that Dad who loved the couch more than he loved spending time with his family. In your life, you always seemed to be able to find a good balance between rest and being active, but when you were active, you always made the most of it and there was always a huge smile on your face. Whether it was riding bikes, walking the dog, playing softball, schooling a bunch of youngsters in basketball, or simply goofing around in the backyard swimming pool, you realized that life was designed to be lived. Even though I didn’t always listen (and boy do I wish I would have), you always encouraged me to get up and get going. You always encouraged me to believe there was life outside of a TV set or computer screen, and since you left I’ve tried to live this out. I’m looking forward to many bike rides together on the other side of Eternity. And if you could talk to the Big Guy upstairs and have him send me a little more muscle mass, I’d be appreciative. Until then, seeya Bub.

Dad, I would never fault you for the sickness you experienced, but I sure wish we could have gotten you the right treatment you needed. You had so much to live for and experience, and I know that Jeff could have helped you fight off the demons and doubts you were facing. I’m still learning from you even after you’re gone, and because I love you I promise that I will always get help when I need it. I’ll never let my emotions overwhelm the plan God has for my life, and I’ll always encourage other people to get help when they need it. If nothing else, you would have loved talking baseball with Jeff. I’d give anything to see the two of you meet—and someday you will. But for now, seeya Bub.

Dad, I would never fault you for the sickness you experienced, but I sure wish we could have gotten you the right treatment you needed. You had so much to live for and experience, and I know that Jeff could have helped you fight off the demons and doubts you were facing. I’m still learning from you even after you’re gone, and because I love you I promise that I will always get help when I need it. I’ll never let my emotions overwhelm the plan God has for my life, and I’ll always encourage other people to get help when they need it. If nothing else, you would have loved talking baseball with Jeff. I’d give anything to see the two of you meet—and someday you will. But for now, seeya Bub.  Jeffrey Yetter, M.Ed., LPCC

Jeffrey Yetter, M.Ed., LPCC

Dad, I don’t think a single day goes by where I don’t replay the sights and sounds of that awful July morning. I constantly fight against my mind to not let the tragedy overshadow the love you showed me, but I’m not always successful. There are days when it’s hard for me to feel happy. There are days when it’s hard for me to feel like I couldn’t have done more to help you. But I never questioned your love for me and for our family. In the moments where life gets really tough and the waters especially overwhelming, I can always feel your presence right there with me. I can always feel you helping me fight against those aftershocks. I’m thankful that you taught me how to love others. I’m thankful that you helped prepare me for the difficulties that would come my way. I’m grateful to have had a Dad who always knew how to comfort me, and I’m thankful that, even from Heaven, you still continue to love me and direct me. Until then, seeya Bub.

Dad, I don’t think a single day goes by where I don’t replay the sights and sounds of that awful July morning. I constantly fight against my mind to not let the tragedy overshadow the love you showed me, but I’m not always successful. There are days when it’s hard for me to feel happy. There are days when it’s hard for me to feel like I couldn’t have done more to help you. But I never questioned your love for me and for our family. In the moments where life gets really tough and the waters especially overwhelming, I can always feel your presence right there with me. I can always feel you helping me fight against those aftershocks. I’m thankful that you taught me how to love others. I’m thankful that you helped prepare me for the difficulties that would come my way. I’m grateful to have had a Dad who always knew how to comfort me, and I’m thankful that, even from Heaven, you still continue to love me and direct me. Until then, seeya Bub.

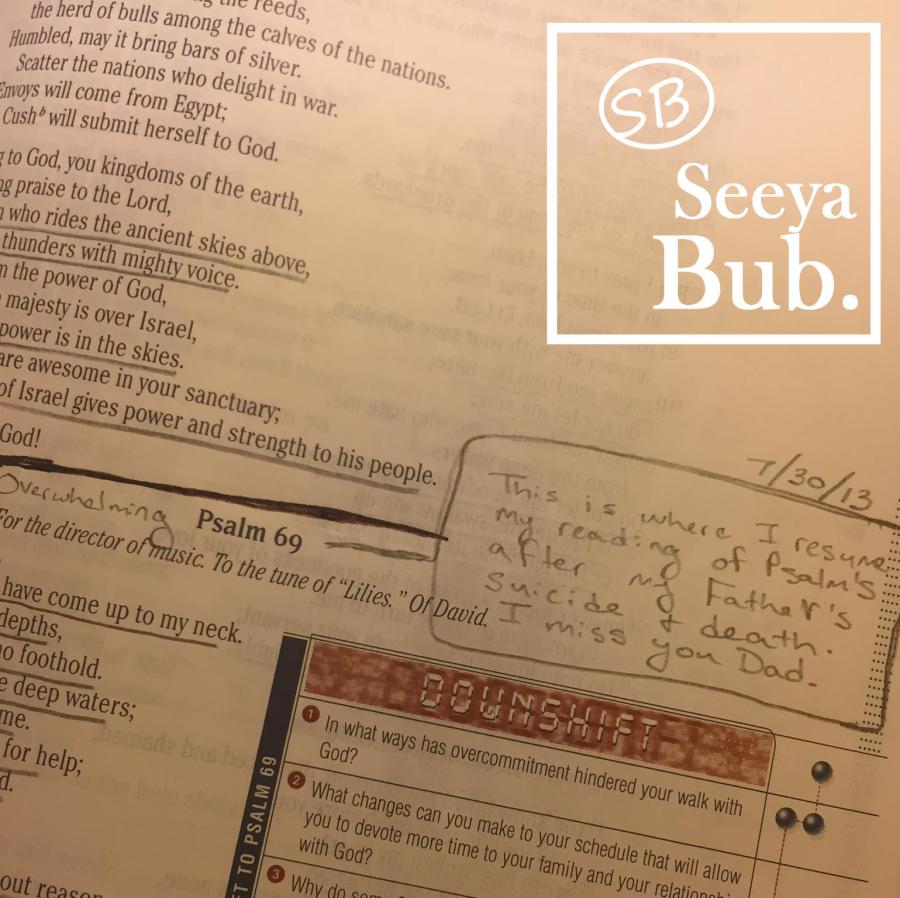

Dad, I’d do anything to go back to that awful day in July 2013 and never have to draw a line in my Bible. But the fact that I’m even drawing that line means you made a tremendous impact on me and my life. You always approached your work with the utmost sincerity and dedication, but there was no job more important to you than being my Dad and the leader of our family. I’ll always be appreciative of that. I’m sad when I see the line, but I smile when I remember the man whose memory deserved it. I promise that my life after the line will honor you and make you proud. I promise that you will not have died in vain—that people will live their lives differently when they hear about you. Keep watching over me. Seeya, bub.

Dad, I’d do anything to go back to that awful day in July 2013 and never have to draw a line in my Bible. But the fact that I’m even drawing that line means you made a tremendous impact on me and my life. You always approached your work with the utmost sincerity and dedication, but there was no job more important to you than being my Dad and the leader of our family. I’ll always be appreciative of that. I’m sad when I see the line, but I smile when I remember the man whose memory deserved it. I promise that my life after the line will honor you and make you proud. I promise that you will not have died in vain—that people will live their lives differently when they hear about you. Keep watching over me. Seeya, bub.