“We had no idea.”

When you’re standing next to a casket at a visitation, you hear lots of comments over and over again. “We will be praying for you.” “Is there anything we can do?” “If you need anything at all, please let us know.” “You’ll be in our thoughts and prayers.”

In reality, who knows what to say? Is there anything you can actually say to take the pain of losing a loved one away? I find myself saying the same things to grieving friends when I attend funerals or visitations. I don’t like that I say it, but I don’t know what else I could possibly say in its place. It’s what we do to show that we love.

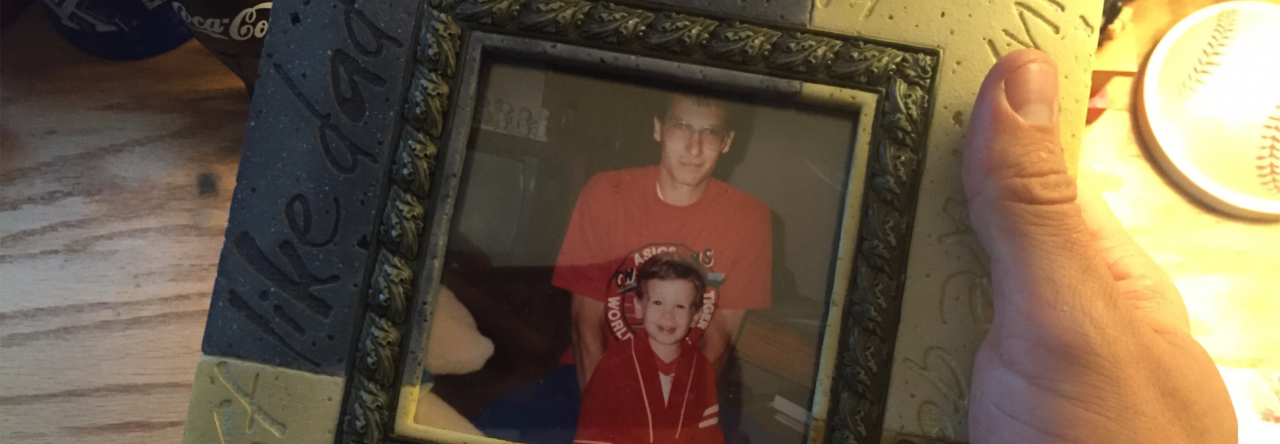

My Dad’s visitation, however, was a bit different. My Dad had passed from suicide, and there was a certain shock of losing someone suddenly who, just a few days prior, had seemed completely healthy. I heard one particular comment more than any other from the more than 1,000 people who came to pay their respects to my Dad.

“We had no idea.”

Over and over and over again, friends and loved ones and coworkers and neighbors and childhood acquaintances made their way through the line, some waiting upwards of a few hours (which still touches my heart in ways I can’t possibly describe). Just a few minutes after the service had started, I remember looking up and being completely overwhelmed by what I saw. Our extremely spacious sanctuary had a line that clung to the entirety of the wall, streaming through the back doors and into the foyer. Who knows how far it went from that point, which was beyond my vision. There were folks sitting in the pews, catching up with one another but I’m sure also trying to figure out why this gathering had even needed to occur.

I tried sincerely to look into the faces of those who came. I tried to assess how people were feeling. I looked out at the other people who had known my Dad—other people who were hurting, too—and I saw the same look on their eyes. Shock. Confusion. Pain. Bewilderment.

My Father had died from suicide, and the flabbergasted looks I saw the night of my Dad’s visitation were justified. Although my Mother and I (along with a close circle of family members) had known of my Dad’s struggle with depression, neither of us thought it would ever get this bad. Neither of us believed that my Dad was hurting as bad as he was. Neither of us believed that the depression could create a stranglehold strong enough to make my Dad feel that life wasn’t livable.

Unlike those folks, we knew; but like those folks, we didn’t.

Many of the people who loved my Dad didn’t know because my Dad wore a mask. I’ve heard that phrase used so many times to describe the coping mechanism that individuals suffering from mental illness will use. They hide their true feelings. They bury the anguish down deep below the surface. They put on a happy face when happiness eludes their heart. That mask metaphor has helped me understand how my Dad was able to hide his depression from those he loved. But more importantly, it’s helped me understand why he would feel the need to hide his depression in the first place.

I anticipated the shock of my Dad’s death in the hearts of those who knew him because so many people knew my Dad as a happy, jovial man. That’s how I knew him, too, even though I would occasionally see into the dark egresses of his depression. Those were usually brief moments confined to a short amount of time. Eventually, that depression would pass—or at least I thought it did. As I reflect on those moments, I am beginning to understand that the depression never truly disappeared. My Dad just got better at coping with it at times. And sometimes, unfortunately, he got better at hiding it.

But most of the time, he was happy.

It’s more than that though. My Dad wasn’t just happy. He was one of the happiest men I’ve ever known. Happy to the point where, as a kid, I just wanted to see him get mad about things to know that he could. My Dad was the guy who could keep a smile on his face in any situation. The man who, in the most difficult moments, could tell the perfectly timed joked to make people laugh. In every circumstance, dark or light, my Dad was cheerful when he interacted with those around him. He had a bright smile, a twinkling eye, and a glistening personality that could instantly comfort other individuals and cheer them up.

Which is why depression confuses me so much. How could a man who could so instantly and effortlessly encourage and lift up others not do it for himself?

His entire life, my Dad worked in labor-intensive jobs. He worked in plants that were often entirely too hot during the summer and entirely too cold during the winter. He built things, and he fixed complex machines, and he worked long hours (a gene for which I have yet to inherit). And no matter the job, my Dad was always happy. He always had a smile on his face. His coworkers absolutely adored him. He was the guy you hoped would join you on a project because you knew you would not only get the job done but have fun while doing it. I wish I could tell him how much he meant to those he worked with.

Then, he would come home. And although he would find ways to relax, he would also find work to do there. He would spend hours sweating in the yard planting flowers and repairing the house. He loved gardening and outdoor work (once again, a gene I have not inherited). He would remodel bathrooms and fix electrical issues. And all the while, Dad would have a smile on his face. All the while, Dad would tell you that he was good, and that he was enjoying life. I wish I could tell him how much that meant to Mom and I. I wish I could go back and tell him that he didn’t have to work so hard.

And it wasn’t just work—his happiness invaded every corner of his life and his soul. Dad would go to church, and he would have a smile on his face while he stood around and chatted with folks for 45 minutes after the service as I rolled my eyes and tugged on his sleeve in an impatient effort to beat the Baptists to Frisch’s for lunch. He would go to my soccer games, which offered very few opportunities for smiles during my short-lived athletic career; but he would smile, and cheer, and even admit to other people that the horrible right fullback was actually his son. When we would go out to dinner and the food or service left something to be desired, Dad would smile and find ways to enjoy the time with his family. It was a contagious happiness that my Dad embodied. And it’s that contagious happiness of his that I miss every single day.

I don’t doubt that in many cases my Dad was simply happier than other people. I think he just had an appreciation for life and the simple things that make it wonderful which few of us are able to truly appreciate. This may sound strange considering that he eventually died from suicide, but my Dad found ways to appreciate life that I’ve yet to tap into.

However, I am also confident that there were likely times in my Dad’s life when he was extremely unhappy underneath the surface but felt as if he couldn’t let people see him in a state of weakness. I know that in the midst of his own personal turmoil, Dad was probably afraid to let people know that he just didn’t feel like himself. He was afraid to let them know that his depression was getting the best of him. He wanted to be a happy, smiling Superman to everyone at all times…and that is an unattainable expectation for anyone, even for my Dad, as great a man as he was.

My Dad was the man who was able to bring joy to other peoples’ lives whenever they needed it most. After his death, I heard countless stories of my Dad’s ability to help others find happiness. I heard stories about times when my Dad would take time out of his day to visit people, to talk with them, and to generally make them feel like someone cared. I heard stories about lunches that he bought for folks, repairs that he made at their homes, and silly things he had done to just get others to laugh a little.

I heard those stories and I believed them. Every single one. I believed them because he did the same thing with me in my life each and every day. There were so many times when I would feel down and my Dad would pick me up. Oftentimes, he didn’t even have to know I was down. I think he could simply sense it. Dad never made me feel ashamed or weak if I wasn’t feeling happy. Dad never judged me or told me to “snap out of it.” Dad gave me compassion. My Dad gave me unconditional and unabated love every single day.

More than anything, I think this is why I hated the fact that my Dad felt as if he couldn’t share his mental illness with the folks around him who loved him. Those folks loved him deeply, and had he shared his struggles, I’m confident that they still would have loved him. And they would have helped him. And they never, ever would have given up on him.

Instead, my Dad felt it was necessary to wear a mask. My Dad felt that he should hide the feelings he couldn’t explain from those he loved most. My Dad wore that mask because he couldn’t bear to let people see the depths of his depression, which he perceived as a personal weakness.

I wish I could tell him that he wasn’t weak. I wish I could tell them that he had no reason to be ashamed. And I wish, more than anything, I could tell him that he didn’t have to wear that mask anymore.

The mask, however, is not a tool of deception; it’s a weapon against embarrassment and shame. My Dad was not a deceitful man, and that’s the point I try to get across to individuals when I talk about depression or mental illness. He didn’t hide his depression because he was attempting to lie or mislead people. He hid his depression because he loved them. He masked his depression because he didn’t want others to worry about them. He buried his depression because he was ashamed of it. And unfortunately, it’s that very shame that led us to bury him.

Dear people, we must arrive at a point in this world where there is no shame surrounding depression and mental illness. And we should do this because…there is no reason for those individuals to feel ashamed. There is no reason for us to wear those masks, and there are other survival mechanisms that actually lead to true healing.

When I think of my Dad on the morning of July 24, 2013 (his last day on this Earth), my heart breaks when I picture how broken he was. He stared at the floor, unable to make eye contact with me. He looked disconnected and detached from everything around him. When I asked him about all of the pressures he was dealing with in life—and boy did he have a lot to deal with—he was even ashamed to admit he couldn’t handle all of those things. At one point, he even said to me, “Yeah, but I should be able to deal with this.”

No, Dad. You shouldn’t have been expected to deal with everything easily. You shouldn’t have been expected to be Superman in every moment of every day.

As much as it tears me apart to think of my Dad on that last day, it also causes me deep pain to think of the weight that must have burdened my Dad’s life from wearing that mask each and every day. This is a heavy mask that those with mental illness are wearing. This is a difficult load that they carry. That mask may hide fear and shame, but it doesn’t eradicate it.

I also know this from personal experience. Although much less severe than my Father’s struggle, my own struggles with anxiety have helped me understand this principle. Dealing with anxiety (or any mental illness) on its own is difficult enough; feeling like you have to lie and convince everyone around you that you’re fine when you’re really not takes that exhaustion to a whole new level. And that exhaustion just continues to fuel the mental illness in a vicious cycle, and before you know it the mask is not merely a coping tactic but a necessary tool for survival.

My Dad’s life may be finished, but his story is not. And what can we do about it? What can I do? What can you do? What can all of those shocked, hurting people who attended my Father’s visitation and funeral do to redeem his story?

Let people know that it’s okay to take off their mask. When individuals are suffering from mental illness, we have to let them know that it’s okay to let down their defenses. We have to let them know that taking off their mask is an act of bravery, not an admission of weakness. We have to let them know that their inexplicable feelings of sadness, despair, nervousness, or guilt are real but remediable. We have to make them feel that there are so, so many more solutions to ease their pain than suicide. Simply, we have to make people feel loved—and not just loved, but unconditionally loved. Loved regardless of their feelings. Loved regardless of their circumstances. Loved regardless of the things they can’t control or fix. Unconditional love is the true mask destroyer.

In order to love others, however, we have to make sure we love ourselves.

That’s why it’s ridiculously important to take off your own mask, too. We can’t tell people to take off their masks if we aren’t willing to take off our own. The best way to promote mental health is to model it. Removing our own mask requires courage and bravery, but it takes the most dangerous weapon mental illness wields—the unjustified humiliation—and completely removes its power. We show others who aren’t okay, in those instances, that we aren’t always okay either.

And we teach them, more than anything, that it’s okay to not be okay…but that it’s never okay to stay that way.

As time moves on from my Dad’s death, I am beginning to see his mask in a new light. I see it as a coping mechanism, not an act of deceit. I see it as an act of love. Yes, an act of love that I wish we could have redirected. But even though he wore that mask, I know that love existed underneath. I know it’s there. I feel it every day—and I’ll never forget it.

Dad, You didn’t have to wear a mask. I think I know why you did. You wore a mask because you loved me and you loved all of us. And you couldn’t bear the thought of letting us down. Dad, you never would have let any of us down. Even in your death, you aren’t letting me down. You could never disappoint me. I would never be ashamed of you, no matter how sick you felt. Dad, you were courageous. You were brave. And you always had a huge smile on your face because you wanted others to smile, too. I know you were trying to be brave, but I wish I could have told you that being vulnerable and getting help was one of the bravest things you ever could have done. Thank you, Dad, for making my life happier. Thank you for teaching me how to enjoy life. And Dad, thank you for being the fighter that you were. Your story is teaching us all so much. Thanks for teaching me how to share it. Until I can say that I love you in person, seeya Bub.

Dad, You didn’t have to wear a mask. I think I know why you did. You wore a mask because you loved me and you loved all of us. And you couldn’t bear the thought of letting us down. Dad, you never would have let any of us down. Even in your death, you aren’t letting me down. You could never disappoint me. I would never be ashamed of you, no matter how sick you felt. Dad, you were courageous. You were brave. And you always had a huge smile on your face because you wanted others to smile, too. I know you were trying to be brave, but I wish I could have told you that being vulnerable and getting help was one of the bravest things you ever could have done. Thank you, Dad, for making my life happier. Thank you for teaching me how to enjoy life. And Dad, thank you for being the fighter that you were. Your story is teaching us all so much. Thanks for teaching me how to share it. Until I can say that I love you in person, seeya Bub.

“But he said to me, ‘My grace is sufficient for you, for my power is made perfect in weakness.’ Therefore I will boast all the more gladly of my weaknesses, so that the power of Christ may rest upon me. For the sake of Christ, then, I am content with weaknesses, insults, hardships, persecutions, and calamities. For when I am weak, then I am strong.” 2 Corinthians 12:9-10 (ESV)

God wanted me to hear that message the day that I originally wrote it down, but he wanted me to live it in this new storm. That was the message God gave to me in a moment of ease to prepare me for a lifetime of perplexing grief. That was the message that God put on Harville’s heart, knowing he would need to pass it along to the members of the flock he cared for. That would be the message of my life, given to help save it.

God wanted me to hear that message the day that I originally wrote it down, but he wanted me to live it in this new storm. That was the message God gave to me in a moment of ease to prepare me for a lifetime of perplexing grief. That was the message that God put on Harville’s heart, knowing he would need to pass it along to the members of the flock he cared for. That would be the message of my life, given to help save it.

Dad, You were always so courageous and so brave, and I wish I had more of that in me. You never let a daunting challenge intimidate you. You believed in your ability, and you believed in your God. Ironically, it was watching your brave example that prepared me to survive the grief of losing you. You taught me that I could do anything if I believed in God and let Him lead my way. Dad, I don’t focus on the one battle that you lost with depression. Instead, I focus on the many years that you fought successfully and conquered your sickness. You tried so hard—for me, for Mom, and for those who loved you. You fought the hardest fight of your life each and every day, and you were unbelievably brave. I’ll always remember that. I’ll always live my life through your example. And until I can see you again and tell you just how courageous you truly were, seeya Bub.

Dad, You were always so courageous and so brave, and I wish I had more of that in me. You never let a daunting challenge intimidate you. You believed in your ability, and you believed in your God. Ironically, it was watching your brave example that prepared me to survive the grief of losing you. You taught me that I could do anything if I believed in God and let Him lead my way. Dad, I don’t focus on the one battle that you lost with depression. Instead, I focus on the many years that you fought successfully and conquered your sickness. You tried so hard—for me, for Mom, and for those who loved you. You fought the hardest fight of your life each and every day, and you were unbelievably brave. I’ll always remember that. I’ll always live my life through your example. And until I can see you again and tell you just how courageous you truly were, seeya Bub.

Dad, I can still go back to that specific Sunday morning and remember the quizzical look on your face when we were handed that baggie with a grape and a raisin. I can remember and picture the way you engaged in that illustration. I can remember you always reminding me many Sundays after that about how I needed to live with a grape heart. But more than all of those memories, I remember the way you lived. I remember the way you loved others. I remember the way you lived and loved with a grape heart every single day. I’m trying to live more like you because you always showed people that your love was more than a sentiment. It meant something and it made a difference. It’s hard to find people who love others the way you did—and the way you still do from above. I still feel your love each and every day. I still feel your love guiding me through all the good times and the difficult times, and I’m thankful that your grape heart lives on. I wish I could tell you this in person. I wish I could give you the praise that you deserved. Until I can see you again and give you a big hug, seeya Bub.

Dad, I can still go back to that specific Sunday morning and remember the quizzical look on your face when we were handed that baggie with a grape and a raisin. I can remember and picture the way you engaged in that illustration. I can remember you always reminding me many Sundays after that about how I needed to live with a grape heart. But more than all of those memories, I remember the way you lived. I remember the way you loved others. I remember the way you lived and loved with a grape heart every single day. I’m trying to live more like you because you always showed people that your love was more than a sentiment. It meant something and it made a difference. It’s hard to find people who love others the way you did—and the way you still do from above. I still feel your love each and every day. I still feel your love guiding me through all the good times and the difficult times, and I’m thankful that your grape heart lives on. I wish I could tell you this in person. I wish I could give you the praise that you deserved. Until I can see you again and give you a big hug, seeya Bub.

Dad, You have no idea how I wish I could wind back the clock and play this song for you. I wish that I could play it, watch you listen, and then say to you that whenever I hear the words I immediately think of you. I desperately wish I could see you thumping your thumb on the console of your truck like you always used to do. I’m sorry that the first time I had a chance to play this for you was at your funeral. So many people have heard the song and told me how perfect it was for you, which is the best testament to your life. It’s what you deserve. Dad, people still talk about how strong you are. People still talk about how courageous you were for fighting through your mental illness for so many years. I know you were hurting desperately, Dad. I know that your soul was troubled. But I pray that you’re able to hear this song in heaven and know that I think of you each and every time I hear it. I’ll always love you, Dad, and I’ll always admire how strong you were. I’ll try to live up to example you gave me—the example that you gave all of us—each day for as long as I live. Someday, I’ll look you in the eyes again and tell you that you were the strongest man I’ve ever known. Until that reunion when we can listen together, seeya Bub.

Dad, You have no idea how I wish I could wind back the clock and play this song for you. I wish that I could play it, watch you listen, and then say to you that whenever I hear the words I immediately think of you. I desperately wish I could see you thumping your thumb on the console of your truck like you always used to do. I’m sorry that the first time I had a chance to play this for you was at your funeral. So many people have heard the song and told me how perfect it was for you, which is the best testament to your life. It’s what you deserve. Dad, people still talk about how strong you are. People still talk about how courageous you were for fighting through your mental illness for so many years. I know you were hurting desperately, Dad. I know that your soul was troubled. But I pray that you’re able to hear this song in heaven and know that I think of you each and every time I hear it. I’ll always love you, Dad, and I’ll always admire how strong you were. I’ll try to live up to example you gave me—the example that you gave all of us—each day for as long as I live. Someday, I’ll look you in the eyes again and tell you that you were the strongest man I’ve ever known. Until that reunion when we can listen together, seeya Bub.

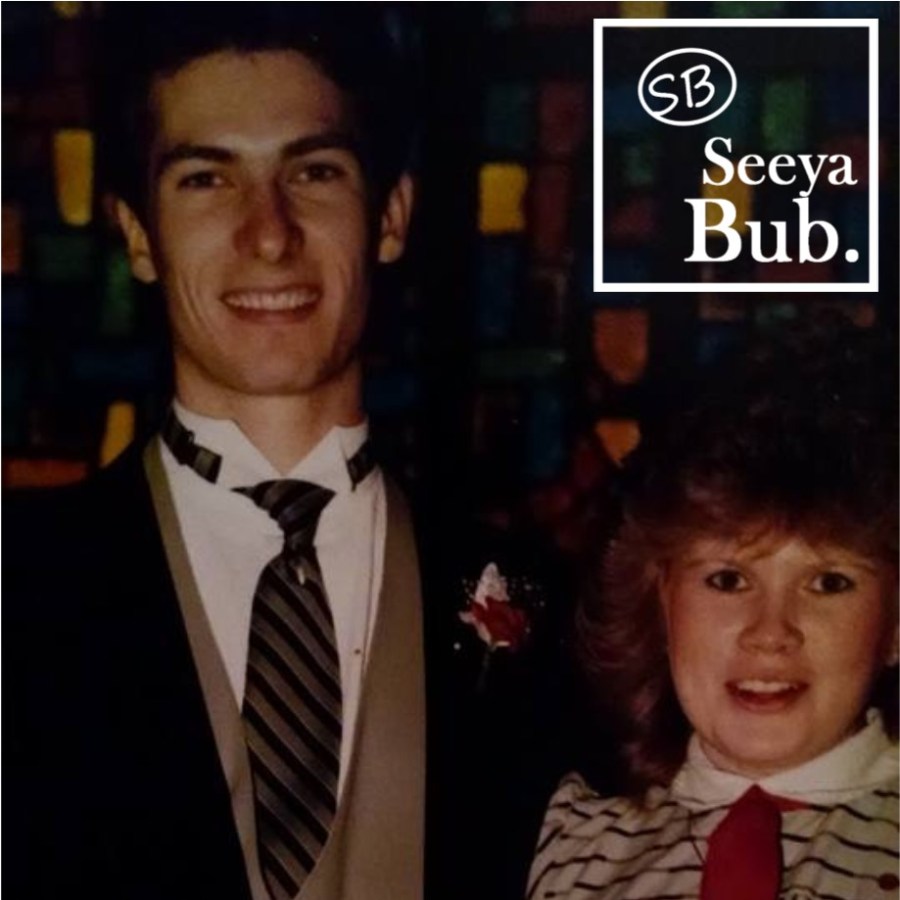

Jeff didn’t know me in high school, but I knew of him. Rather than equitably distributing golf talent across all the boys at Fairfield High School, God had taken mine and consolidated it all into Jeff Sullivan. Jeff was a graceful golfer. He would hit shots that I wouldn’t even believe I could hit in my own dreams. Natural talent? Maybe a bit. But more than anything, Jeff is one of the hardest working athletes I’ve ever seen. He spends more time honing his abilities than anyone, and it shows in his competitive spirit.

Jeff didn’t know me in high school, but I knew of him. Rather than equitably distributing golf talent across all the boys at Fairfield High School, God had taken mine and consolidated it all into Jeff Sullivan. Jeff was a graceful golfer. He would hit shots that I wouldn’t even believe I could hit in my own dreams. Natural talent? Maybe a bit. But more than anything, Jeff is one of the hardest working athletes I’ve ever seen. He spends more time honing his abilities than anyone, and it shows in his competitive spirit. I was 9 years old when “Papa Sully”, as my high school teammates would later name him, first took me to the driving range. One trip, and I was hooked. As I mentioned before, this was when Tiger madness was really starting to hit its peak. Tiger had already won 3 U.S. Junior Amateurs and had just locked up back-to-back U.S Amateurs. The next year, he would turn pro, and I was probably on my Dad’s last nerves!

I was 9 years old when “Papa Sully”, as my high school teammates would later name him, first took me to the driving range. One trip, and I was hooked. As I mentioned before, this was when Tiger madness was really starting to hit its peak. Tiger had already won 3 U.S. Junior Amateurs and had just locked up back-to-back U.S Amateurs. The next year, he would turn pro, and I was probably on my Dad’s last nerves! From that day forward, my golf is played for him. Not only to win, but to show him that I can be the man and player that he always wanted me to be. To show great sportsmanship, character and class on the golf course. That’s why I play the game now. In 2011 and 2012 I wanted to win our city tournament SO bad, even more than ever before because I wanted to do it for my Dad. I couldn’t get the job done until 2013 and I will remember that win more than any other as long as I play the game.

From that day forward, my golf is played for him. Not only to win, but to show him that I can be the man and player that he always wanted me to be. To show great sportsmanship, character and class on the golf course. That’s why I play the game now. In 2011 and 2012 I wanted to win our city tournament SO bad, even more than ever before because I wanted to do it for my Dad. I couldn’t get the job done until 2013 and I will remember that win more than any other as long as I play the game.

Jeff “Sully” Sullivan

Jeff “Sully” Sullivan

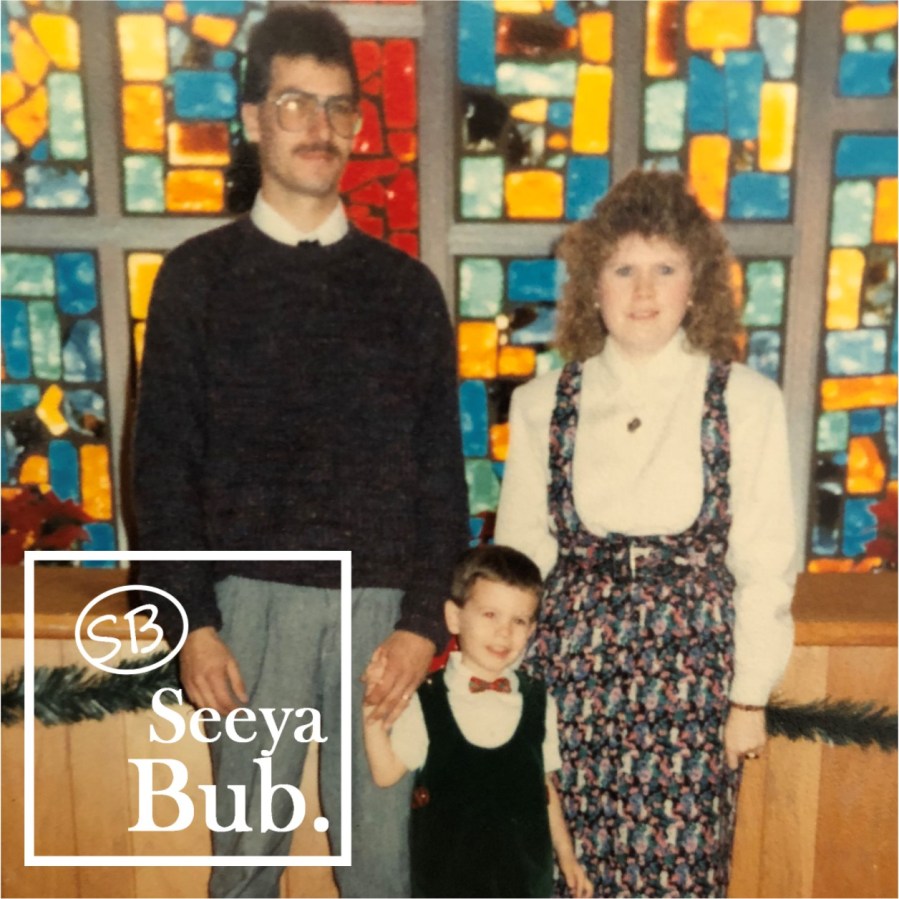

Dad, Christmas hasn’t been the same without you. I have such wonderful memories of the special Christmases we spent together as a little family. You bought thoughtful gifts for all of us. You laughed as our family pup would open up gifts, just like you always taught them. You put amazing detail into the wrapping and the decorating, and you had a smile on your face no matter how hectic things got. You made us especially happy around Christmas, but you honestly did that each and every day. Now, your memory and your spirit get us through the tough times and remind us to continue celebrating in spite of our grief. Dad, please continue reminding us how we can make the Christmas season special. Continue watching over us as you rest among the angels. I miss you so much, Dad. I know that I still have many wonderful Christmases ahead of me, but I desperately long for that first Christmas with you in heaven. Until that day when we can celebrate together again, Merry Christmas, bub.

Dad, Christmas hasn’t been the same without you. I have such wonderful memories of the special Christmases we spent together as a little family. You bought thoughtful gifts for all of us. You laughed as our family pup would open up gifts, just like you always taught them. You put amazing detail into the wrapping and the decorating, and you had a smile on your face no matter how hectic things got. You made us especially happy around Christmas, but you honestly did that each and every day. Now, your memory and your spirit get us through the tough times and remind us to continue celebrating in spite of our grief. Dad, please continue reminding us how we can make the Christmas season special. Continue watching over us as you rest among the angels. I miss you so much, Dad. I know that I still have many wonderful Christmases ahead of me, but I desperately long for that first Christmas with you in heaven. Until that day when we can celebrate together again, Merry Christmas, bub.

Whether you know it or not, you’ve seen C.F. Payne’s work. You’ll find his art on the covers of Time Magazine, Readers Digest, Sports Illustrated, The New York Times Book Review, MAD Magazine, U.S. News and World Report, The Atlantic Monthly, Texas Monthly, Boys Life and more. He has illustrated popular children’s books, and his art hangs in art museums all across the country.

Whether you know it or not, you’ve seen C.F. Payne’s work. You’ll find his art on the covers of Time Magazine, Readers Digest, Sports Illustrated, The New York Times Book Review, MAD Magazine, U.S. News and World Report, The Atlantic Monthly, Texas Monthly, Boys Life and more. He has illustrated popular children’s books, and his art hangs in art museums all across the country. If you’re somebody, C.F. Payne has likely captured you in one of his illustrations. President Barack Obama, Joe Nuxhall, Magic Johnson, Albert Einstein, President Ronald Reagan, David Letterman, Secretary of State Hillary Clinton, Andy Griffith, Katie Couric, President Thomas Jefferson, the Pope…heck, he’s even done Santa!

If you’re somebody, C.F. Payne has likely captured you in one of his illustrations. President Barack Obama, Joe Nuxhall, Magic Johnson, Albert Einstein, President Ronald Reagan, David Letterman, Secretary of State Hillary Clinton, Andy Griffith, Katie Couric, President Thomas Jefferson, the Pope…heck, he’s even done Santa!

Mom slowly ran her hands over the paper. “Oh, Scott…” she said. She cried as I put my hand on her shoulder, and I recounted the story of how that portrait came to be.

Mom slowly ran her hands over the paper. “Oh, Scott…” she said. She cried as I put my hand on her shoulder, and I recounted the story of how that portrait came to be. Dad, Christmas mornings aren’t the same without you. We miss your smile. We miss your silly Dad humor and goofiness. We miss everything about having you there with us. But deep down, in our hearts, we know you’re there. And now, we have a beautiful portrait to remind us that you’re always there. I know what a humble guy you were here in this life, and I’m sure you would feel completely undeserving of having your own portrait done by C.F. But Dad, this is exactly what you deserved. Your life was more important and consequential for me and those whom you loved than most people could ever hope to have. Your life was incredible. Your character was impeccable. And you made people feel loved each and every day. And now, I can gaze upon a beautiful portrait of your face and remind myself that those things have never left us. Keep watching over me, Dad. I miss you terribly, and I long for another Christmas morning like the ones we used to have. I know it’s going to be a long time until we have that again, but oh what an amazing day that will be. Until our first Christmas morning together again, seeya Bub.

Dad, Christmas mornings aren’t the same without you. We miss your smile. We miss your silly Dad humor and goofiness. We miss everything about having you there with us. But deep down, in our hearts, we know you’re there. And now, we have a beautiful portrait to remind us that you’re always there. I know what a humble guy you were here in this life, and I’m sure you would feel completely undeserving of having your own portrait done by C.F. But Dad, this is exactly what you deserved. Your life was more important and consequential for me and those whom you loved than most people could ever hope to have. Your life was incredible. Your character was impeccable. And you made people feel loved each and every day. And now, I can gaze upon a beautiful portrait of your face and remind myself that those things have never left us. Keep watching over me, Dad. I miss you terribly, and I long for another Christmas morning like the ones we used to have. I know it’s going to be a long time until we have that again, but oh what an amazing day that will be. Until our first Christmas morning together again, seeya Bub.

Dad, I really, really miss you on Halloween—and every other holiday for that matter. The Bert and Ernie jack-o-lanterns you carved for us every year were spectacular. Not just because of your talent, but because you took the time to do them over and over again when I’m sure you had other things you would rather carve. My childhood was special because I had tremendous, loving parents. I wish I had said it more then, but thank you. Thank you for always doing the little things to leave me with big memories. Thank you for showing me on the holidays and every day that you loved me and that you cared about me. And thanks for all the Bert and Ernie pumpkins. I wish I could have them one more time, but until I get to see you and thank you face to face, seeya Bub.

Dad, I really, really miss you on Halloween—and every other holiday for that matter. The Bert and Ernie jack-o-lanterns you carved for us every year were spectacular. Not just because of your talent, but because you took the time to do them over and over again when I’m sure you had other things you would rather carve. My childhood was special because I had tremendous, loving parents. I wish I had said it more then, but thank you. Thank you for always doing the little things to leave me with big memories. Thank you for showing me on the holidays and every day that you loved me and that you cared about me. And thanks for all the Bert and Ernie pumpkins. I wish I could have them one more time, but until I get to see you and thank you face to face, seeya Bub.

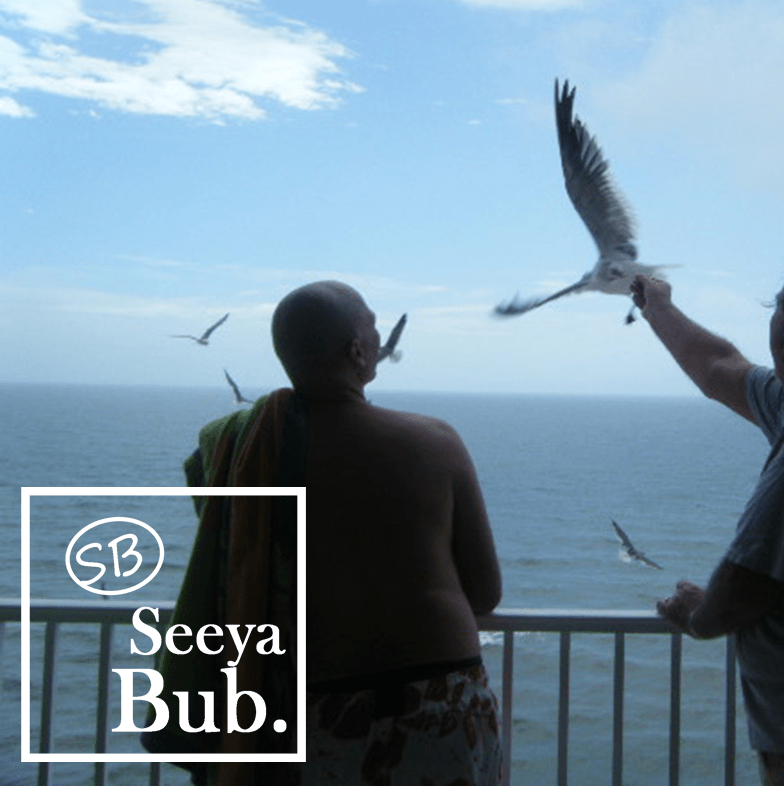

Dad, When I think of the things you enjoyed, I always think of bonfires. They provided you with such amusement, but deep down I think they also provided you with a lot of peace. Your mind and soul just seemed to be quieter and happier when you were sitting around a good fire. I wish I could take back all of those days when you’d ask me to come sit with you and I said no. I wish I had spent more time with you around the fire, but there never would have been enough time with you because you made life so exciting and full of love. It may not be around a fire, but I’ll spend more time with those I love because I realize that I should have spent more time with you when I had the chance. I love you, Dad. I miss you like crazy, although I don’t miss the constant bamboo explosions. Okay, who am I kidding…of course I miss those. Thanks for all the fires we did share, but more importantly thanks for keeping the fire in my heart going even after you’re gone. I’m looking forward to that first bonfire together on the other side…I’ll bring the flamethrower. But for now, seeya Bub.

Dad, When I think of the things you enjoyed, I always think of bonfires. They provided you with such amusement, but deep down I think they also provided you with a lot of peace. Your mind and soul just seemed to be quieter and happier when you were sitting around a good fire. I wish I could take back all of those days when you’d ask me to come sit with you and I said no. I wish I had spent more time with you around the fire, but there never would have been enough time with you because you made life so exciting and full of love. It may not be around a fire, but I’ll spend more time with those I love because I realize that I should have spent more time with you when I had the chance. I love you, Dad. I miss you like crazy, although I don’t miss the constant bamboo explosions. Okay, who am I kidding…of course I miss those. Thanks for all the fires we did share, but more importantly thanks for keeping the fire in my heart going even after you’re gone. I’m looking forward to that first bonfire together on the other side…I’ll bring the flamethrower. But for now, seeya Bub.

Dad, I miss you every single day. I replay our last conversation together in my head so frequently. I can see your face, I can hear your voice, and I can feel the warmth of our last embrace before I left the house that day. Dad, I’m so thankful that we told each other that we loved one another one last time before I left that day. And I’m sorry for all the days when I didn’t tell you I loved you. When I didn’t express my gratitude and appreciation for all the things you did for our family. When I didn’t tell you how proud I was of you for fighting so hard. Your death has proven to me just how fragile life really is. I hate that it took losing you for me to learn this lesson. Dad, you are still teaching me important life lessons every single day. I pray for those who are hurting this week in the aftermath of the Las Vegas shooting, and even though their departure (like yours) was far too soon, I hope that you are welcoming those 59 brave souls home in Heaven. I love you, Dad. Until our last words can be our first on the other side, seeya Bub.

Dad, I miss you every single day. I replay our last conversation together in my head so frequently. I can see your face, I can hear your voice, and I can feel the warmth of our last embrace before I left the house that day. Dad, I’m so thankful that we told each other that we loved one another one last time before I left that day. And I’m sorry for all the days when I didn’t tell you I loved you. When I didn’t express my gratitude and appreciation for all the things you did for our family. When I didn’t tell you how proud I was of you for fighting so hard. Your death has proven to me just how fragile life really is. I hate that it took losing you for me to learn this lesson. Dad, you are still teaching me important life lessons every single day. I pray for those who are hurting this week in the aftermath of the Las Vegas shooting, and even though their departure (like yours) was far too soon, I hope that you are welcoming those 59 brave souls home in Heaven. I love you, Dad. Until our last words can be our first on the other side, seeya Bub.